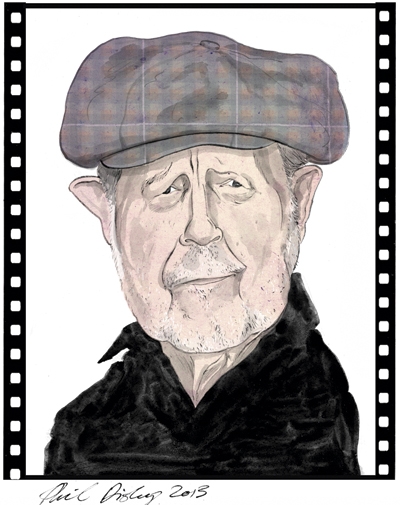

‘Oh, some of my films have been attacked with absolute vitriol!’ said Nicolas Roeg, 85, and still one of the darkest and most innovative of post-war British directors. We were sitting in his study in Notting Hill; nearby in Powis Square is the house Roeg used for his 1968 debut, Performance, starring Mick Jagger as the rock star who entices a gangster (James Fox) into a drug-induced identity crisis. The film was shelved for a year before Warner Brothers dared to release it.

‘The critics didn’t always get it then — but they do seem to now,’ said Roeg.

Roeg was born in 1928 in St John’s Wood into a vaguely bohemian background. A lifetime’s accumulation of books, awards and framed pictures of his former wife, the actress Theresa Russell, spills into the room. Roeg, a rumpled, softly spoken man with a very English reserve, has just published a book of reflections on film, The World is Ever Changing, in which he chronicles (among other things) his ‘flawed life’ as a director.

‘I liked the book a lot,’ I said.

‘It’s very nice of you to say so. The last thing I wanted was to write an academic treatise or to lecture at the reader from the pulpit.’ Instead the book is tinged with a sense of amazement and the self-examination of an older man looking back on a most unusual career.

Roeg was eight when he discovered film. ‘Going to the cinema was an adventure. I was always a bit arty-farty as a boy. “Come on, Mr Arty-Farty,” my sister used to say to me.’ Babes in Toyland, with Laurel and Hardy, was the first movie to open up the ‘mystery’ to Roeg of celluloid make-believe. Roeg’s has always been a painterly imagination.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in