In the morning darkness at the reception of our central Kharkiv hotel, 25 miles from the Russian frontlines, the night porter’s face was creased with sleep. As we made our way towards the door to catch the early express to Kyiv, he handed us a small keyring with a yellow and blue plastic ornament. They had been made by local children.

The man was large, muscled rather than hammy, and had a trim beard. In the several days we had stayed at the hotel, he had not shown a trace of emotion. Now he almost looked as if he might cry.

‘Perhaps next time we meet there will be peace,’ he said struggling with his English. Then he said it again: ‘Perhaps there will be peace.’

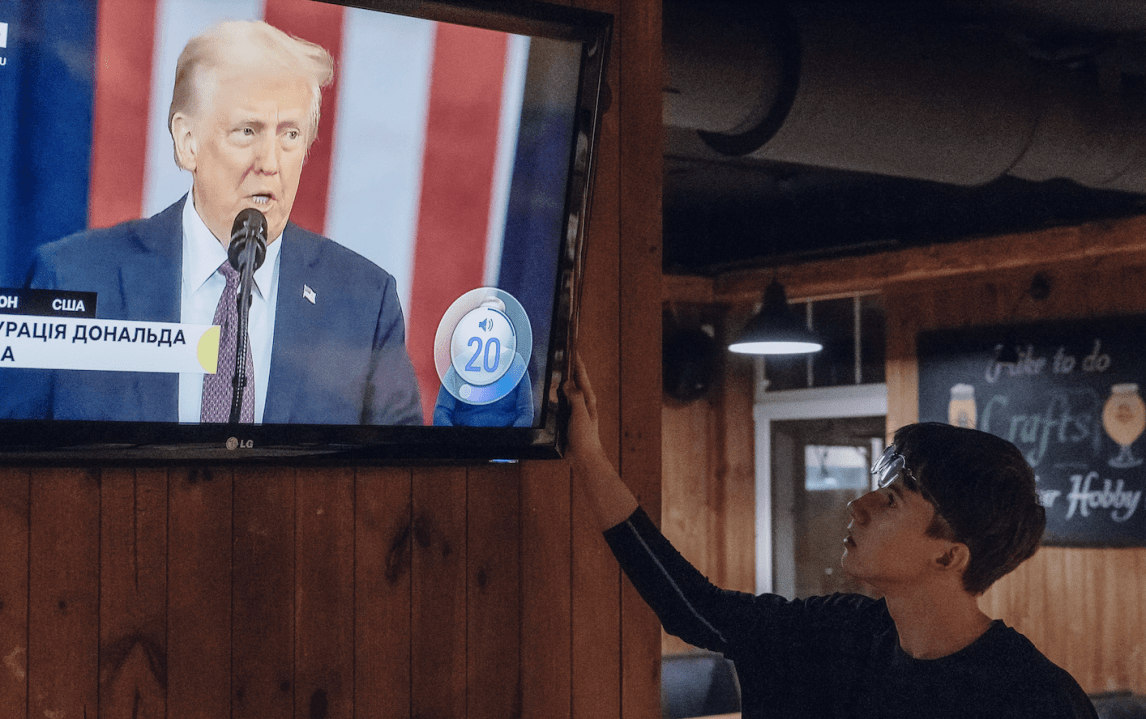

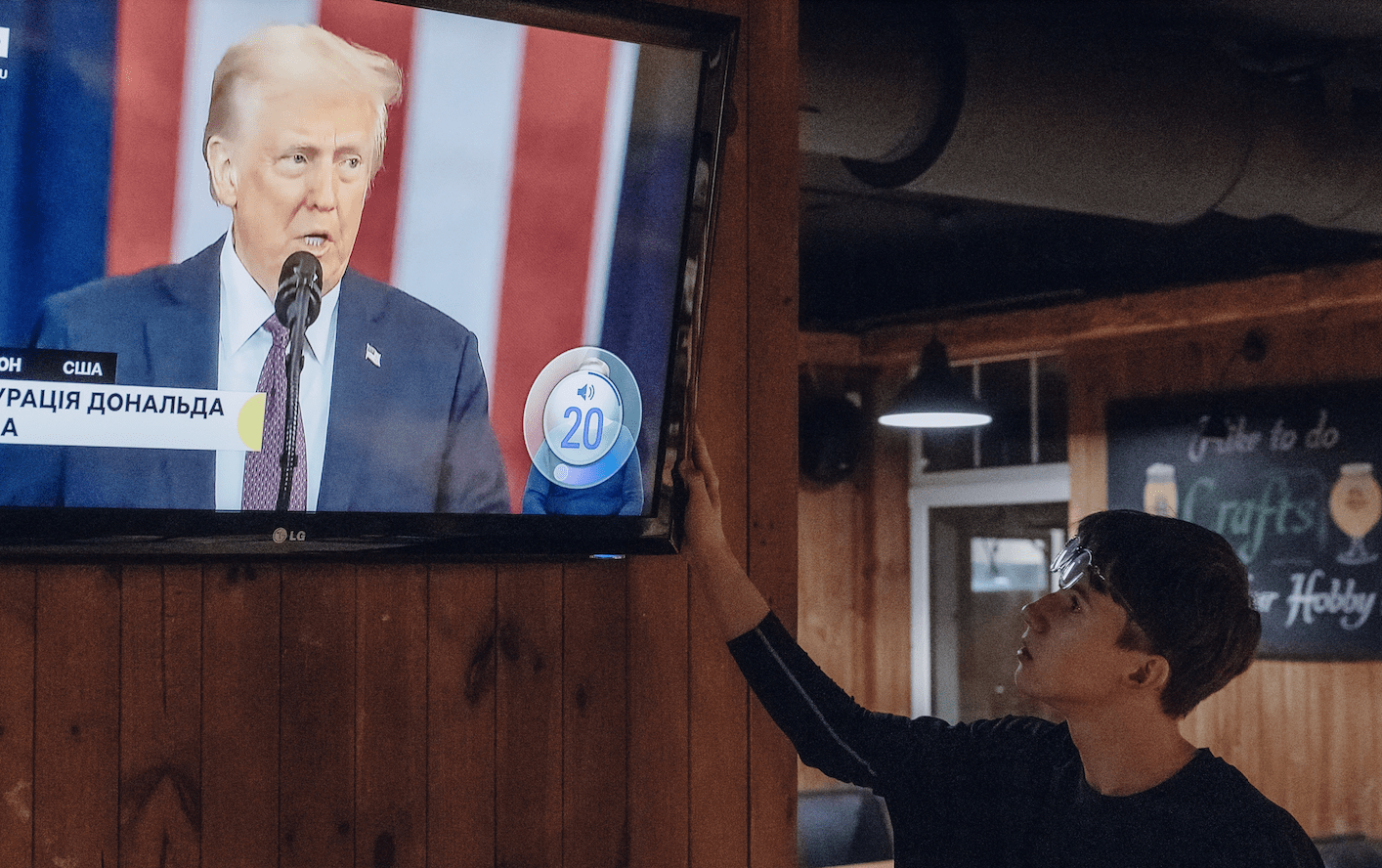

On the night of the inauguration, we sought a bar where locals might be watching the event on television

It was the second time we had stayed at this hotel, nestled in a courtyard in Ukraine’s second city. The first time, last spring, we heard several explosions a day as Russian drones and missiles impacted. After one such attack we went to the scene to find a wrecked building and a large hole in the road.

Several people died in the attack. Then a fireman was killed when the Russians executed a ‘double-tap’ – targeting the same spot again – a tactic specifically designed to kill rescuers.

The dead man’s son, also a fireman, was working only a few blocks away. When he was told he broke down and sobbed.

This time Kharkiv was quieter and attacks rare. There was even talk that perhaps Vladimir Putin, the Russian president, was on best behaviour, intent on impressing upon Donald Trump that Moscow was ready for peace talks. But of course nobody really knew.

Between 7 November, when Trump won re-election, and 20 January, when he was inaugurated for a second time, Ukrainians did their best to pivot towards the new reality in Washington. President Volodymyr Zelensky had enjoyed a good working relationship with Joe Biden, who had been a solid if plodding backer of Ukraine in the war with its larger neighbour.

But there had also been a growing sense that, with the Democrats in office, Kyiv was never going to get enough weapons to stop the advance of Moscow’s forces, which would have to happen if the country was to enter negotiations with Russia on an equal footing.

And so when Trump won the election, and although leading Republicans had threatened many times to cut military aid, there was a quiver of optimism in war-weary Ukraine.

In European countries polled on how they felt about Trump’s return to power, Ukrainians came out as the most in favour with 44 per cent saying they trusted him. (The second most in favour was Viktor Orban’s Hungary with 37 per cent.)

While campaigning Trump had initially promised to end the three-year-old war in only 24 hours. Ukrainians feared that meant Trump would go above their heads and cut a deal with Putin. Then Ukraine might be pressured into both accepting a huge loss of land and be denied any meaningful security guarantees against future attack.

Indeed Trump had made little secret of his disdain for Ukraine. “Zelensky is the greatest salesman in history,” he said, and he hadn’t meant it as a compliment.

But then, as inauguration day approached, there were more mixed signals from Washington. Keith Kellogg, who was appointed as the presidential envoy to stop the war, told Fox News that he had been given 100 days rather than 24 hours to sort things out.

Among the Ukrainians I spoke to there was a mixture of hope, trepidation and a sort of weary punch-drunk indifference as the second Trump term approached. ‘A man of his age should be sitting by a lake fishing,’ a man in Kharkiv told me. ‘You need to be educated and trained to be a good politician,’ another, an electrical engineer, said.

An hour or so to the east, in a blacked-out house only a mile or two from the frontline, and with incoming shells rattling the building, a 43-year-old combat medic with the call-sign Volvo was even more scathing when I asked if Trump’s becoming president would be better for Ukraine.

‘It will be better for Trump,’ he said. ‘Trump doesn’t love Ukraine. He loves himself.’

On the night of the inauguration itself – Ukraine is seven hours ahead of Washington D. C. and it was already dark in Kharkiv – we sought a bar where locals might be watching the event on television. But we couldn’t find one. Some locals said they were reluctant to gather in public places for fear they would be targeted by the Russians and preferred to watch on a laptop at home.

Eventually we settled on a restaurant and watched Trump speak on our phones.

In the event, Trump failed to even mention Ukraine. Perhaps, after issuing a flurry of executive orders to close down the US border with Mexico and axing tranches of Biden’s new green energy strategy, he had decided he had bigger fish to fry.

But then Marco Rubio, the new secretary of state, said in an interview that the US was searching for a solution that would last more than a couple of years. That looked more positive for Kyiv.

Finally, two days after the inauguration, Trump broke his silence on the war. Answering a reporter’s question, he said that Vladimir Putin, with whom he had something of a bromance during his first term, was destroying Russia.

Later, posting on Truth Social, his social media channel, Trump wrote to Putin:

‘Settle now, and STOP this ridiculous War! IT’S ONLY GOING TO GET WORSE. If we don’t make a ‘deal’, and soon, I have no other choice but to put high levels of Taxes, Tariffs, and Sanctions on anything being sold by Russia to the United States, and various other participating countries…’

If it wasn’t exactly music to Ukrainian ears, at least Trump’s opening salvo had been fired at Moscow not Kyiv. For our sleepy night porter it was perhaps just a small sign of hope.

Comments