‘She was dead even before I became aware of her existence.’ The menacing opening line of this gripping novel is not about the title’s Mary Rose but about another six-year-old girl, Margaret Sutton, who has been abducted, raped and murdered in the Kent woods.

The story is told from the perspective of Mary Rose’s father, Rowan Anderson, who spends most of his time in London, writing a biography of the scientist Hertha Ayrton and feuding with his possessive girlfriend, Gloria. He periodically visits his daughter and his wife, Cressida, in their country cottage. Cressida busies herself with domestic chores in the cramped space, compulsively ironing sheets, painstakingly preparing elaborate meals (which Rowan flushes down the lavatory), and ‘stuffing Mary Rose with iron and vitamins, with cod liver oil, wheat germ and yeast and various other nutritional supplements’ to counter the child’s sickliness.

Rowan dislikes Cressida’s beloved Kent cottage, but praises it out of ‘polite hypocrisy’, while despising the way they have ‘learned to skate so gracefully on the ice of [their] own politeness’. He copes by escaping to the village pub to drink vast quantities of whisky. Troublingly, it transpires that he was so drunk on the night that Margaret was abducted that he has no memory of his actions.

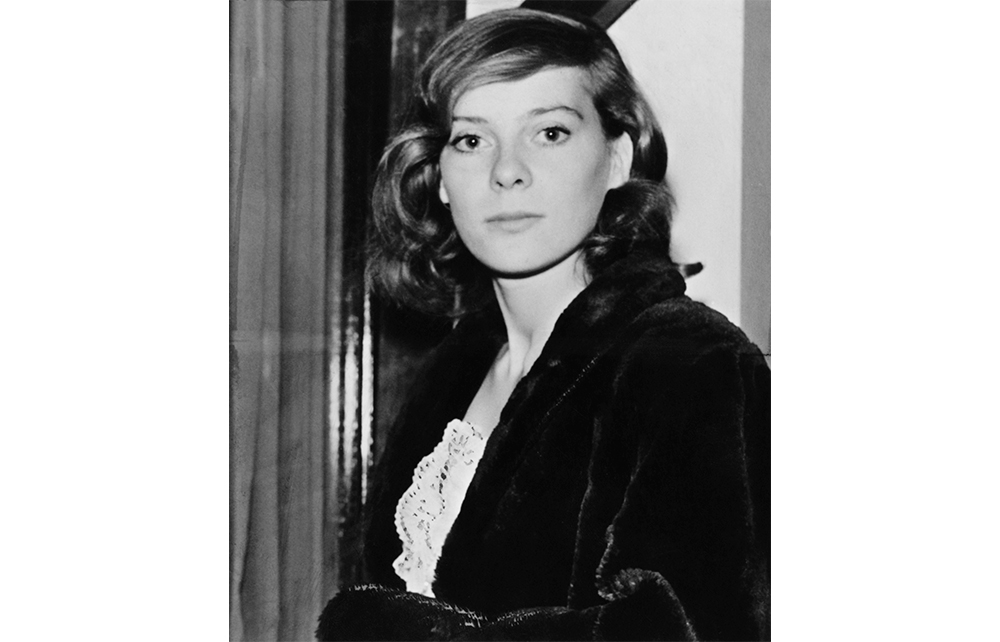

First published in 1981, this is one of three novels by the late Caroline Blackwood that Virago are reprinting. A wealthy Anglo-Irish socialite, Blackwood was perhaps better known as the wife and muse of the painter Lucian Freud, the composer Israel Citkowitz and the poet Robert Lowell. She began writing in her thirties, and this horrible, wonderful tale is testament to the fact that she had as much creative talent as her men.

It is disconcerting to read a story narrated by the possible perpetrator of such a crime, and it becomes increasingly disquieting to witness Cressida’s growing obsession with it. She keeps vigil over Mary Rose, installs bars on the windows and embroils the child in her fixation, taking her out of school, bolting her in their bedroom and describing the tragedy to her in graphic detail. She releases Mary Rose for Margaret’s funeral and Rowan watches the two of them go: ‘The big black figure being followed like a duck by a pathetically small black duckling.’ The wry humour adds another layer of discomfort. What hope is there for the little girl, caught between a neglectful, dissolute father – who might be a rapist murderer – and a crazed, controlling mother?

The Fate of Mary Rose leaves one unsure whether to be more frightened by the threat of paternal physical brutality or maternal psychological violence; whether a child should trust an absent father or a domineering mother. With both the woods and the cottage transformed into places of darkness and menace, Blackwood’s world is chilling indeed.

Comments