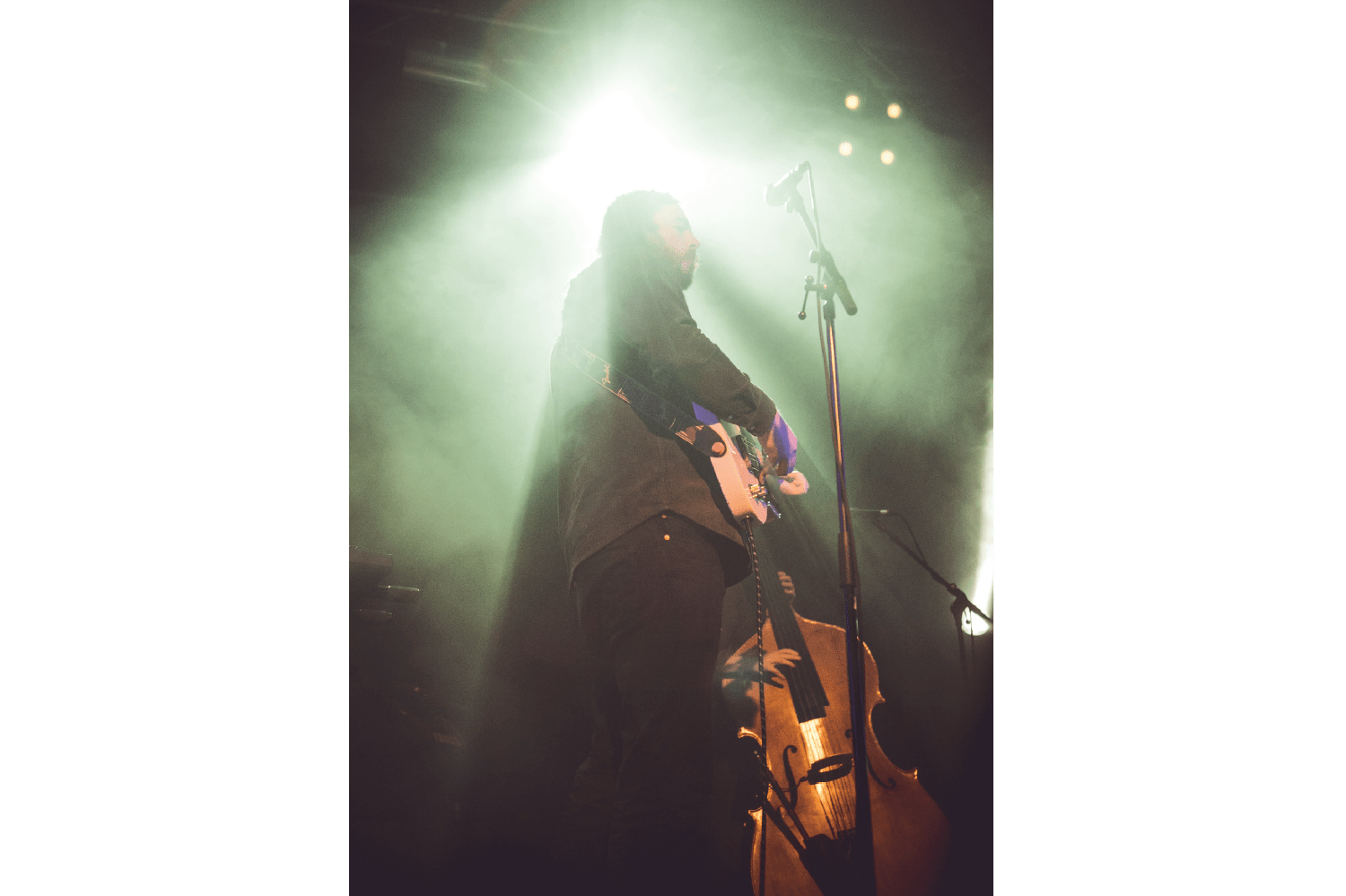

John Francis Flynn is monumentally good. He’s kick-yourself-for-missing-him good. He’s so good that when he spoke between songs in the upstairs ballroom of an old Irish pub in Tufnell Park, it was almost a disappointment: how could the man making this extraordinary music be so normal?

Flynn is part of a cohort of Irish musicians revisiting traditional music. There’s the Mary Wallopers, in broad terms the most Pogues-ish. There’s Lankum, shortlisted for the Mercury Prize for their eyebrow-raising, droning experimentalism. There’s Lisa O’Neill, subdued and stern. And there’s Flynn, whose music dances from the unadornedly old-fashioned and Irish – the ‘Tralee Gaol’ played solo, on tin whistle – into something entirely different. He recast the American folk song ‘I Wish I Was a Mole in the Ground’ into something new and different, part Nick Drake, part post-punk; the English sea shanty ‘Shallow Brown’ became something of a meditation, stately and glowering, owing more to post-rock’s imposing stillness than to the records that usually carry the writing credit ‘Trad Arr.’.

How could the man making this extraordinary music be so normal?

It’s of course far from unprecedented to combine folk with other music. More recently we’ve had the Gloaming, the Irish-American folk supergroup who in the 2010s became diaspora superstars. They also played something that sounded like it had been spliced with post-rock. But the Gloaming’s post-rock elements were the kind that soundtrack BBC nature documentaries about the awesome majesty of Iceland. They came from the stirring, wondrous end of things, the Sigur Ros end. What Flynn has taken from post-rock is the sort of stuff that soundtracks Netflix series about surviving in a world of reanimated corpses. His songs come from the paranoid, grubby end of things, the Mogwai and Slint end. These were songs that could draw blood.

‘My Son Tim’, a cry against the conscription of young Irishmen to fight against Napoleon, was punctuated by screeches, wails and walls of electric guitar from Brendan Jenkinson, as if Gang of Four were jamming with the Wolfe Tones.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in