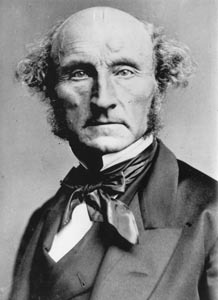

Britain has had few public intellectuals. The one undeniable example was John Stuart Mill who lived from 1806 to 1873 and whose utterances dominated the more intelligent public debates of the mid-19th century — predictably he was keenly studied by Gladstone and mocked by Disraeli. In the last year of his life he was persuaded to be godfather to the infant Bertrand Russell, who was the nearest runner-up in the UK public intellectual stake. Mill’s own influence was on the wane for much of the 20th century when Marx became the centre of attention. But it has been rekindled in the past few decades as faith in collectivist nostrums has evaporated and there have been numerous academic studies of different aspects of his work. The time is therefore ripe for a full-scale modern biography which provides reliable pointers to the main doctrinal issues, but concentrates on the man and his career. This is amply provided by Richard Reeves in his well, but unobtrusively, documented new book.

Mill’s father John was a close associate of the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham and himself a prolific writer. This is perhaps more important than the widely known fact that he taught his son to read Greek at the age of three. Another reasonably well-known fact about John Stuart Mill was that he suffered a deep crisis of belief at the age of 20, when he concluded that, even if all the reforms which he advocated could be achieved in an instant, it would not bring him any great joy. He buried himself in the Romantic poets and was also influenced by the prose works of Coleridge.

Once he had got over his mental crisis, Mill returned to the political philosophy of his father and Bentham and tried to give it more content rather than turn it upside- down.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in