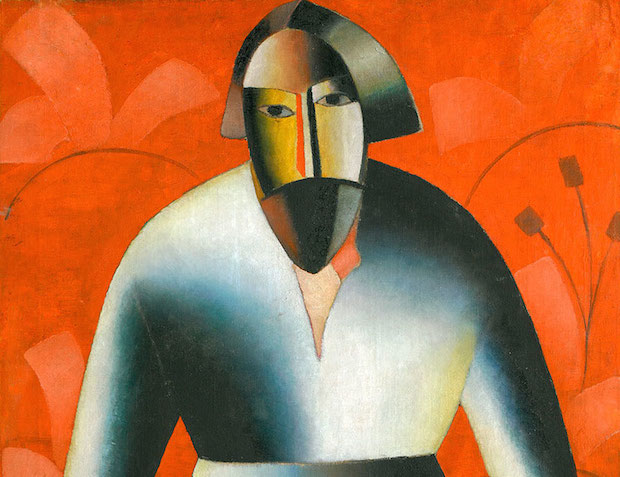

Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) is one of the founding fathers of Modernism, and as such entirely deserves the in-depth treatment with which this massive new Tate show honours him. But it should be recognised from the start that this is a difficult exhibition, making serious intellectual and emotional demands on visitors, as art enters the realm of pure thought, utterly divorced from the comforting world of appearances. Malevich was one of the first great revolutionary practitioners of abstract art, a pioneer who made work of singular beauty and resonance, but his path is not always easy to follow. Perhaps with this in mind, the exhibition starts with a room of early, mostly figurative work, in which Malevich is shown experimenting with different ways of depicting. These range from the full but softly stated realism of ‘Portrait of the Artist’s Father’ (1902–3), to a more heavily textured and pointillist approach in ‘Church’ and ‘Houses in the City’, to the more decorative and folk art influenced ‘Little Village’ (1908), and the emblematic ‘Self-Portrait’ (1908–10).

Get Britain's best politics newsletters

Register to get The Spectator's insight and opinion straight to your inbox. You can then read two free articles each week.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Comments

Join the debate for just $5 for 3 months

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for $5.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just $5 for 3 monthsAlready a subscriber? Log in