To understand how the Tories ended up in such a muddle about who they are and what they stand for, take a walk down any of the nicer streets in Boris Johnson’s constituency. North Hillingdon is as idyllic now as it was a generation ago: spacious houses, with large drives, built before the war. The houses were, once, more or less affordable. One property on Parkway, for example, was bought for £175,000 just over 20 years ago. It’s now valued at £1 million. And what’s true in Hillingdon is true of the rest of the country too.

The asset boom that started at the turn of the century has transformed the finances of families across the country, turning modest-income retirees into unexpected millionaires: a new ‘assetocracy’. Homeowners have to sell to access the money, but their children can expect to inherit life-changing amounts — just as long as their parents don’t end up needing long-term care, in which case the costs can gobble up the inheritance.

‘My job is to protect you or your parents or grandparents from having to sell your home to pay for the costs of care,’ said Boris Johnson after becoming prime minister two years ago. This was quite a statement. But to do it would cost billions and the Prime Minister had also promised, in his manifesto, not to raise taxes. So what to do? Should he keep his promise to the voters, or create a safety net for the asset-rich? It’s telling that he chose to protect the assetocracy.

The emergence of this new class in the space of the past two decades has changed politics more than any party likes to admit. Wealth has become concentrated in a group of people who now decide British elections. Before the crash, 7 per cent of British pensioners were millionaires, as measured by household wealth. Now, it’s 25 per cent — some three million people. A further three million are half-millionaires, with at least £500,000. That’s one out of every eight people eligible to vote.

At each election, parties compete to bribe this demographic. Labour’s ‘winter fuel payments’ and pension rises were the start, followed by the Tory triple-lock pension. The next frontier: to guarantee that no one would have to sell their house to pay for care, no matter how rich they are. This prospect was dangled in front of homeowners by Blair, Brown and Cameron, but none of them went through with it. They baulked not only at the expense but also at what it would mean. The traditional logic of the welfare state — that those with power and money help those with less of it — would be turned on its head.

Wealth has become concentrated in a group of people with the power to decide British elections

After minimal consultation with his cabinet, let alone his party and the country, Johnson has now completed this inversion, with a £12 billion tax funding a new deal. Some of the money will, at first be used to help clear an NHS backlog. Some will help families who can in no sense be described as rich.

But after the NHS waiting list has begun to ease, the tax becomes a care home insurance scheme, and the refusal to impose any means-testing has big implications. No one, no matter how rich, will have to pay more than £86,000 for their care in old age.

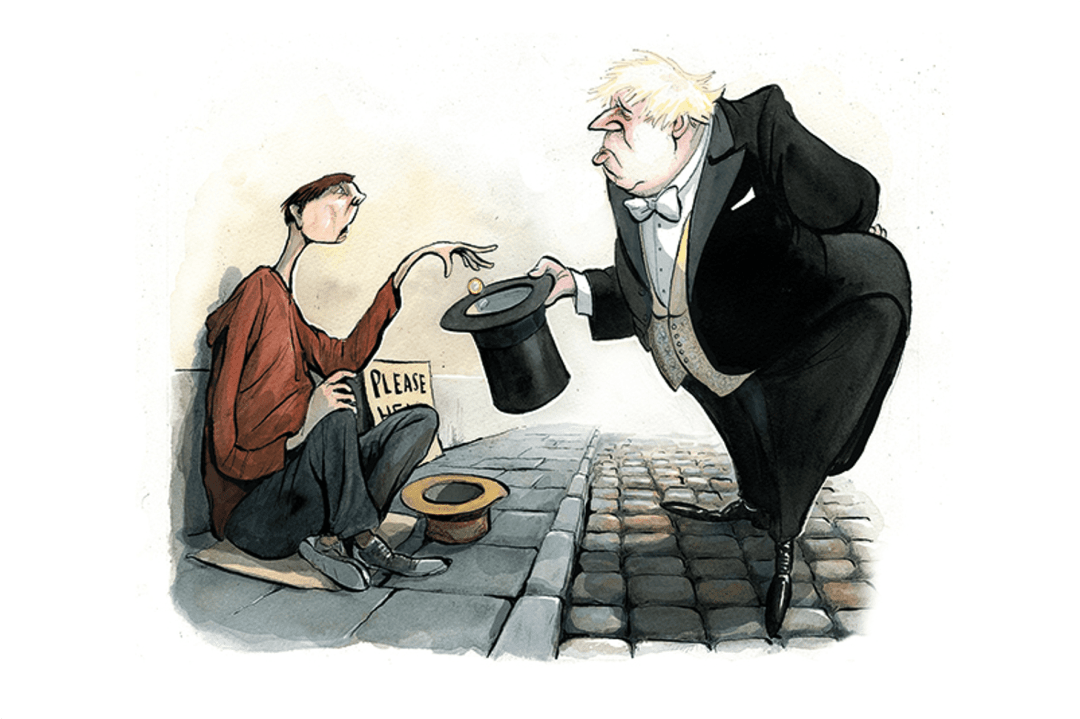

This raises tricky political questions: how can you justify increasing taxes on the working poor to safeguard the assets of the stonkingly rich? What, morally, is the problem with someone selling their house — or any other asset — to pay for care? Isn’t Toryism about providing equal opportunities, a ladder for everyone to climb? Why then would any Tory want to make life even easier for those already at the top of the ladder, at the expense of people on the lower rungs?

To understand, you need to do the electoral arithmetic. Age, not social class, has become the new dividing line between Labour and the Tories. The under-25s broke three to one for Labour in the last election — but this was no problem for Team Boris because the over-65s chose him by four to one. His gamble now is that the political backlash from tax rises will be balanced out by gratitude from affluent homeowners.

To the Tory MPs trying to make sense of this twist in their party’s mission, this is what’s baffling. Surely, with the political power his election win bought him, Johnson should have found a way to help the less well off, who are already paying too much for shoddy care? Under the old system, there was a (pretty low) floor: no one would pay for their care if it meant reducing their assets below £14,250. And there was — still is — an urgent need for social care reform. But this isn’t about ‘fixing’ the system, though it’s a nightmare to navigate and entirely failed to protect care-home residents against Covid. What we have now is an asset pledge. No reform at all.

The Tories have posed as the party of a property-owning democracy since Noel Skelton introduced the phrase in The Spectator in 1923. To Margaret Thatcher, owning property wasn’t about getting rich; it was about the chance to take control, to claim a stake in a growing economy. The idea was that homeownership would promote what Shirley Letwin called the ‘vigorous virtues’. A home-owner starts to see society in a different way and to feel that they have more agency, more power to change their life story. How, Thatcher asked, could popular capitalism work if people did not have capital?

This week the Prime Minister called groups of backbenchers to No. 10 to explain his plan, but they left more confused than ever. He tried to sum up his thinking by saying in private what he no longer says in public: that it’s about the assets. ‘It stands for something very conservative,’ Johnson said to one of the groups of MPs he’d invited to No. 10 — ‘the right to pass on money’.

Is this really the Boris Johnson definition of conservatism: a protection racket, where the tools of the state are used to extract money from minimum-wage workers and pass it on to the better off?

I’ve spoken to many Tories who are worried by all this, but as much as they dislike it, hardly any decided to vote against it. The depressing truth is they don’t have a better idea, and they agree about the realpolitik.

When Theresa May called a snap election in 2017, and was predicted a landslide majority, she felt confident enough to say she would not subsidise those who could easily afford to meet their own care costs. She was then attacked for proposing a ‘dementia tax’ and her campaign imploded. Tory MPs still talk about the furious reaction on the doorstep from voters worried about losing their homes. Rightly or wrongly, the Conservative conclusion was that no one can win power by confronting the asset-owning classes.

But even in political terms, the current plan is just a short-term solution. And it doesn’t just accept but actually deepens the already stark divide between those with assets and those without. The latest round of quantitative easing will further fuel the asset boom (cheap money always does), meaning more wealth for the richest. The division, inequality and subsequent resentment mean that the legacy of this self-interested approach could well be social unrest and a dramatic Tory defeat.

A more confident Tory party could have a broader conversation. They could ask if anyone, rich or poor, wants to live in a country where the best chance of acquiring serious wealth is being born into (or marrying into) the right family. This was the theme of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century: that the system is rigged and that work can never pay as much as owning capital, so huge wealth taxes are needed. The Tory response, eight years ago, was to say that the asset boom was a freak and taxes on low-paid work would be cut.

It’s harder to make that claim now that the Tories are quite literally increasing the tax on care-home workers on minimum wage to better insulate the wealth of the people they care for. An analysis by Policy in Practice puts a figure on it: a carer on the minimum wage of £8.91 an hour will end up paying £112 more in tax a year. Added to the coming reduction in welfare, they’ll soon be £1,082 a year worse off.

‘In every situation, we seem to shaft the young in favour of the old,’ says one of the newer MPs. ‘That’s what we did in the pandemic. Then afterwards, rather than repair the damage, we shaft them again. And until they start voting, that’s not going to change. We’ll get away with it because, no matter how bad we are, Labour is worse.’

It’s a fair point. An energetic and eloquent Labour leader would be in a very strong position. He or she would be able to hammer the Tories for breaking their tax promises, or point out that this 1.25 percentage point rise in tax on salary is actually a 2.5 percentage point rise, as it’s paid by both the employer and the employee. They could and should attack the PM on the grounds that it will depress future wages. They could point out that the Tories are undermining trust in politics, and that trust in politics is vital. And all because no one bothered to think of alternatives.

One opposition MP summed this up well. ‘It was the Prime Minister’s unique selling proposition that he could improve public services without raising taxes,’ he said in the chamber. ‘Recall the gigantic posters that sprouted up all over the country with his signature appended, the better that we might believe his pledge.’ The government, he added, ‘have been revealed in their true colours as taxers and spenders and believers in the NHS unreformed and — as it is — monolithic and monopolistic’.

That was the young Boris, attacking Tony Blair for a more modest version of this National Insurance rise. It’s an interesting quote because it shows the extent to which politics has moved full circle. The Tories now pour cash into the ‘monopolistic’ NHS and plan to take taxes to the highest level in British peacetime history. Higher than Attlee, Healey, Brown or Blair ever dared. Yes, the pandemic was expensive. But at every stage in that pandemic, the Tories have reached for the most expensive solution.

‘The biggest problem with all of this is that we’re misjudging the elderly,’ says one minister. ‘They don’t want bribes: they want a better country for their grandchildren, the ones we’re now taxing to death. We could have found a better way out if we had thought.’ Johnson’s bet, now, is that the economy recovers so strongly that his ‘levelling up’ will come to look like a genuine agenda. But if that bet fails, the next Labour leader should have a fairly easy task.

Fraser Nelson will be joined on Spectator TV this week by Peter Hitchens, Andrea Leadsom and Nick Newman. To watch, go to spectator.co.uk/tv

Comments