As anniversaries go, the timing could hardly be more apt. As Europe braces itself for the next Islamist attack, the next assault on our civilisation, a season of events marks the 500th birthday of a book that outlined an enlightened vision of the ideal society. Utopia 2016 is a year-long celebration of Thomas More’s Utopia at London’s Somerset House, where the Royal Society and the Royal Academy used to meet. Somerset House is a building that encapsulates the free-thinking values of the Enlightenment, and More’s Utopia is a book that encapsulates the Renaissance sensibilities that built it.

We all know what sort of society Isis wants (the clue’s in the name), but what sort of society do we want? What rights are we defending? The right to have a good time all the time? Or do we believe in something deeper? Five hundred years since it was written, under a repressive theocracy that forbade free speech and beheaded its opponents, does Utopia hold any clues?

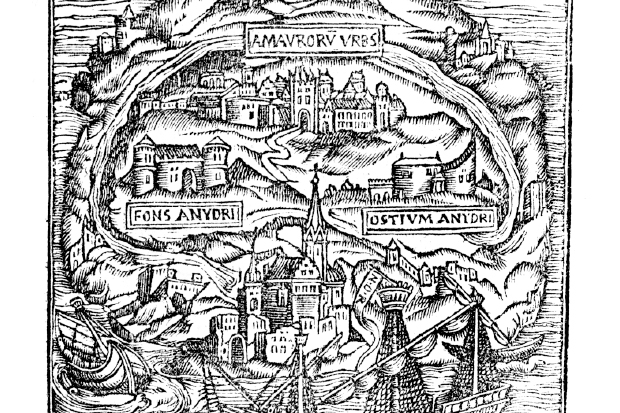

As every British schoolboy (and schoolgirl) used to know, in 1535 Sir Thomas More — or Saint Thomas, if you’re a Catholic — got his head chopped off for refusing to recognise Henry VIII’s newfangled divorce-friendly C of E. As Henry’s Chancellor (the first layman to hold this office), More had bumped off a fair few dissidents himself, though he didn’t much like beheading them — he preferred to burn them alive (both these methods of execution seem to be similarly popular in today’s Islamic State). In 1516, the same Thomas More wrote ‘a splendid little book, as entertaining as it is instructive’ (like modern authors, he got to write his own blurb) about a fantasy island called Utopia, a prosperous republic without kings or aristocrats, where divorce is allowed, priests are free to marry, women can take holy orders and freedom of religion (even atheism) is permitted.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in