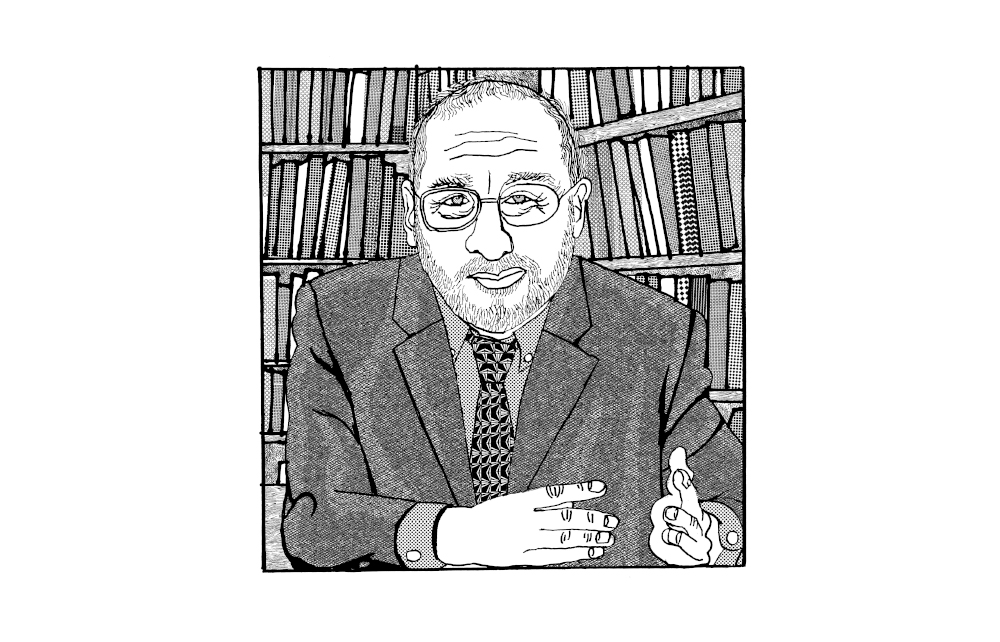

When Joseph Stiglitz talks, the left listens. The Nobel laureate has advised multiple Democratic presidents and the World Bank, where he worked as chief economist and senior vice president. He’s long been a leading critic of the liberal leanings that have dominated the West’s economic policy for four decades. So when we meet in The Spectator’s office, I ask him if the Labour party has sought his advice. It wouldn’t be unthinkable.

‘I just met with, in a TV show, one of the Labour shadow ministers. We had a good discussion,’ he says, smiling. But the New Keynesian economist is in the UK for four days, and his new book, The Road to Freedom, is keeping him busy. No summits on ‘securonomics’ this time.

The aim of the book is to reclaim the word ‘freedom’ from the economic right, which Stiglitz believes has forgotten about trade-offs. The book’s thesis is that ‘one person’s freedom can often amount to another person’s unfreedom’. Once you accept this premise, the Columbia professor argues, the case for ‘coercion’ – and a bigger state – becomes much more palatable.

‘The idea was that if you lift up the top, everybody would benefit. That clearly didn’t work’

‘Traffic lights are a kind of coercion,’ Stiglitz, 81, says. ‘In a place like New York or London, if you didn’t have traffic lights, you would have gridlock and you couldn’t go anyway. So by having this little coercion that you’re not allowed to go, everybody has more freedom.’ It’s the same example he uses at the start of his book: a ‘metaphor’, he says, for how in ‘lots of other areas where if we co-operate, we expand what we can do’.

It’s a curious critique, not least because free-market economics is about voluntary co-operation (Adam Smith’s butcher and baker famously come together, voluntarily and out of their own interest, to make the world spin round).

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in