There are three people in every conversation about Jeremy Corbyn’s grim past. I have noticed this before but renewed interest in his paid work for Iran’s Press TV confirmed it for me.

First, there’s the anti-Corbynista, who points out one outrage or another. This might be Corbyn’s ‘friends’ in Hamas and Hezbollah, his inviting a hate preacher to tea on the Commons terrace, or the time he was arrested at a ‘solidarity’ demo for the Brighton bomber. These are well-documented facts and the anti-Corbynista believes, despite melancholy experience, that reason and evidence still have some purchase in current political debate.

He is quickly disabused, again, when the Corbynista interjects. He may deny the facts (‘MSM smear!’) or claim they have been misinterpreted (the theory that Corbyn was involved in the Northern Ireland peace process, for example – a fabrication debunked by both nationalists and unionists). Whataboutery is a common tactic (pointing out his appearances on Iranian TV often brings a triumphant ‘The Tories sell weapons to Saudi Arabia!’) as is pleading the passage of time. Even where the facts are not challenged, they may be decried as part of a plot to ‘get’ Corbyn, or, creepiest of all, declared irrelevant because Corbyn is such a good, decent, caring man.

Above all this sits the ‘anti-anti-Corbynista’ (a term coined by Damian Counsell) – a person who professes independence from or even opposition to Corbyn, but whose true enmity is reserved for Corbyn’s critics. Like Cold War anti-anti-Communists, the anti-anti-Corbynista believes the bigger problem is not the threat but the response to the threat. If only these hysterics would shut up, friendlier, more measured analysis would guide the Corbyn project to moderation. Their response to criticism of Corbyn then is to point out that voters are indifferent to Corbyn’s past, and counsel critics to stop banging on about it. This makes the anti-anti-Corbynista more objectionable than the Corbynista.

Anti-anti-Corbynism resolves the schism within the left by reducing a philosophical dispute to a squabble over strategy. This is a tempting get-out clause. By pretending the divisions in Labour are political, and surmountable, rather than moral, and fundamental, the rancour can finally be brought to an end, the centrists can return to the fold, the true believers can welcome them graciously, and everyone can focus on moving forward and beating the Tories. The Corbynista may dispute the veracity of facts but the anti-anti-Corbynista questions their virtue. He doesn’t want a truce between left and right; he wants the truth to surrender.

Should it? After all, plenty of politicians have thrived despite their past. Yitzhak Shamir made it to the top of Israeli politics despite the assassination of Lord Moyne. Martin McGuinness became deputy first minister of a country that once cowered in the shadow of his crimes. Austria’s most celebrated socialist, Chancellor Bruno Kreisky, appointed former Nazis to his ministry and was belligerent towards those who objected. Circumstances change and people do, too. The past is more than prologue but it shouldn’t be the end of the story. Forgiveness humbly sought and graciously given absolves the sinner but it allows the rest of us to move on too.

Yet forgiveness is impossible when it comes to Jeremy Corbyn because he does not believe he did anything wrong. He evades and dissembles, allowing for a minor slip here and there, but he has not (perhaps cannot) admit that three decades of his career were dedicated to embracing, excusing and making common cause with the very worst at home and abroad. His worldview from the start has been a series of ‘antis’ — anti-war, anti-Israel, anti-America — and now that he must be for things, he struggles because that is practical politics and practical politics is hard and complex and those complexities can no longer be snorted away. So Corbyn has settled into denying his past without resiling from it, as his disturbing record is repackaged as the buffering decency of a wise, kindly grampa. It is a spin job so audacious that, in private moments, Lord Mandelson must wonder at its brutal daring.

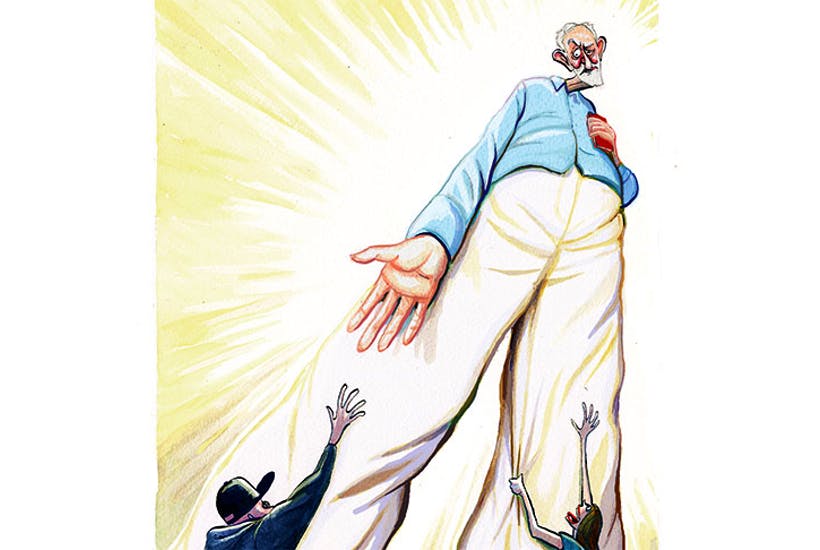

The conversation about Corbyn’s past is a proxy debate about the place of truth in politics and public life. The anti-Corbynista believes truth should be all-controlling; and the Corbynista believes much the same, except he assumes truth is whatever Jeremy says, because Jeremy is good and therefore true and his opponents evil and therefore wrong. Jeremy cares about the little people and that is why the money changers and the Pharisees persecute him. Saint Jeremy of Islington and the Allotments, a Christ-like figure for an age in search of new religion. It is said to be patronising to point this out, to note that Corbyn, like all demagogues, preys on the need of the despondent for a soothsayer. He appeals to those who feel they’ve been left behind. Indeed he does but then so do all demagogues. Blessed are the poor and the meek but their virtue is not without limits. The dockers who marched against Mosley were right; the dockers who marched for Powell were not.

Corbyn is a reactionary’s idea of a progressive and for a strain of progressive he has made reaction respectable. Not the Corbynista, who after all believes his man is the victim of smears and plots, but the anti-anti-Corbynista, who knows the truth but regards it as expendable. The revolution is coming; the facts can be sorted out afterwards. This is cynical because it not only demeans the truth, it exploits the faithful who will be bitterly disenchanted should Corbyn ever come to power. The Corbynista reveres hope, the anti-Corbynista facts. The anti-anti-Corbynistas looks on both with contempt.

Comments