Philip Hensher has narrated this article for you to listen to.

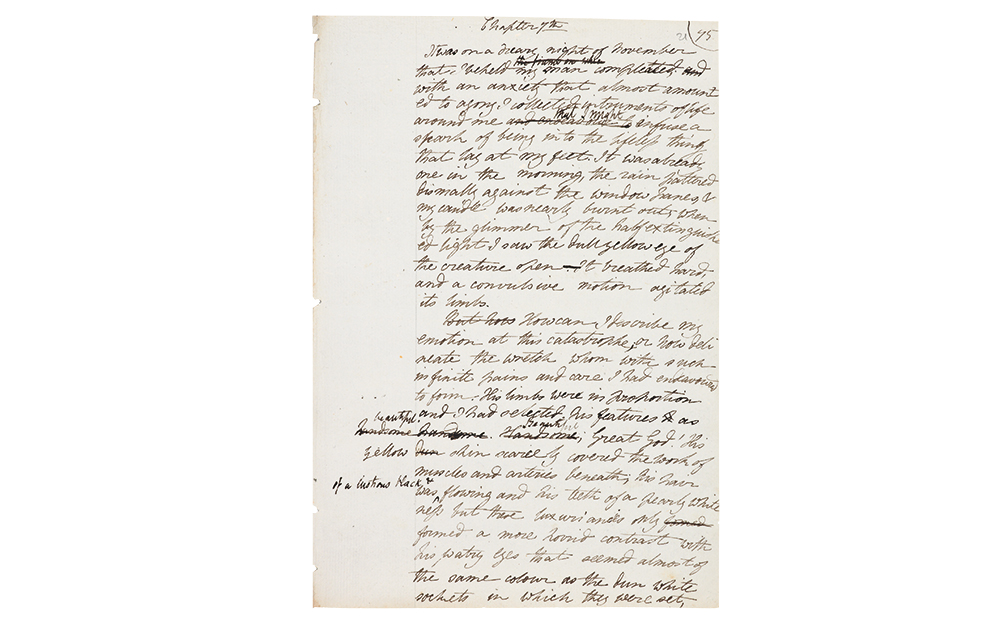

The early stages of a literary work are often of immense interest. It is perhaps a rather tawdry kind of interest, like paparazzi shots of a Hollywood starlet taking the bins out before she’s put her make-up on. Of course it’s extraordinary to think that some of the most famous characters, events and lines in literature weren’t as we now know them but had to be struggled towards. Sometimes these efforts have the anachronistic but unavoidable sense of somebody getting it wrong.

Textual bibliographers have carefully classified the different steps a work takes from manuscript to first edition and subsequent versions. Perhaps we could go further in search of a writer’s progress. There are the inchoate thoughts, remote from any conscious intention – perhaps a sound, a mood, a phrase, a voice, a movement. Then some words that might merit being written down, even though no coherence is discernible. (But writers work in such different ways that none of this is universal.) Soon we start to have more consecutive writing – a few lines, or even a scene. A draft follows, which could be modified in any number of ways. At some point, eyes other than the author’s fall on the manuscript. Suggestions are made, changes might even be enforced, and agreement is reached on a final manuscript, which is sent to the printer and out to an audience.

Some or none of these stages may be preserved for the curious investigator. Occasionally we have everything, from the first jottings to the last authorised text. In many cases, however, writers have destroyed all other versions apart from the one first published, either by conscious decision or just custom. Sometimes even in these instances we still have signs of the author’s thoughts and decisions, because the work appeared in a subsequent rethought form.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in