Elizabeth Strout’s fourth book about Lucy Barton comes on the heels of Oh William!, shortlisted for this year’s Booker Prize. That book tracked Lucy’s growing friendship with her first husband, William, after the death of her second. In Lucy by the Sea, she accompanies William to Maine to ride out the pandemic. Closing the door of her New York apartment, she does not know that she will never see it again; that she will lose a friend and a family member to Covid; and that her relationship with William and her two grown daughters will change.

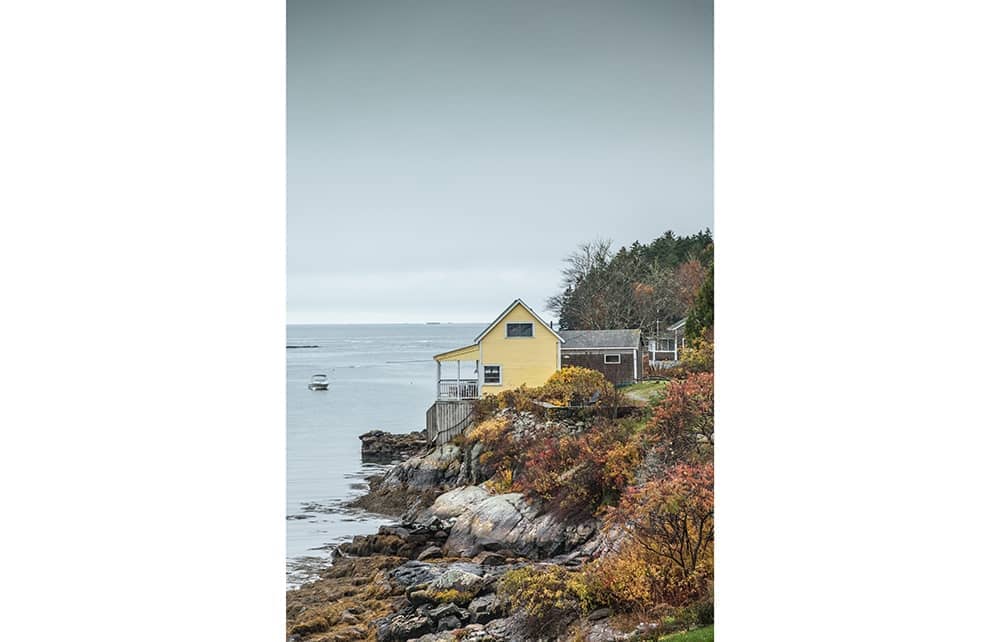

Lucy is at sea at first: she hates the cold, the locals’ distrust of out-of-staters, even the ocean’s ‘bitingly salty smell’. As ‘just a few weeks’ turns into a year, however, she comes to know the tides and appreciate the beauty of the jagged coast. She develops friendships with Bob Burgess – one of the brothers in The Burgess Boys (2013) – and with Charlene Bibber, a cleaner with opposing political views whom she meets volunteering at a food pantry.

Lucy by the Sea recalls with precision the peculiarities of life during the pandemic: bleaching groceries, rifts over masks and vaccines, the elasticity of time. The anxiety makes Lucy, a novelist, fear that she ‘will never write another word again’. Strout’s stand-out skill is rendering the emotional riptide roiling under ordinary lives. As the Booker judges observed: ‘No one writes interior life as Strout does.’

Where the novel feels flat, however, is when it forgoes interior life to recount current events, including the Black Lives Matter marches after the murder of George Floyd and the US Capitol insurrection. As hot-button topics such as child labour in Bangladesh and gender nonconformity get shoe-horned into the narrative, and Lucy’s usually endearing naivety veers perilously close to twee, one starts to miss the curmudgeonly Olive Kitteridge, the character who earned Strout the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 2009.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in