Dominic Cummings may have left Whitehall but his spirit lives on. Pat McFadden, the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, has repurposed Cummings’s call for ‘weirdos and misfits’ as a plea for ‘innovators and disruptors’. Downing Street this month launched an ‘AI Ideas’ competition in pursuit of bright sparks. A hackathon will follow. In No. 10 and 11, aides channel Cummings’s language as they talk of acting as an ‘insurgent’ government. ‘We’re all Dom now,’ says one government figure.

In one area, Cummings’s influence on the new government is most apparent: the diagnosis of a failing state. Keir Starmer’s chief aide Morgan McSweeney has never met Cummings, but these days they share an analysis of what has gone wrong in Britain. The economy is flatlining, the public sector has grown but become less productive, Whitehall reform seems impossible, and nothing ever gets built. A generation of homeowners leaves behind them a new generation of rent payers. The country has chronically underinvested in defence.

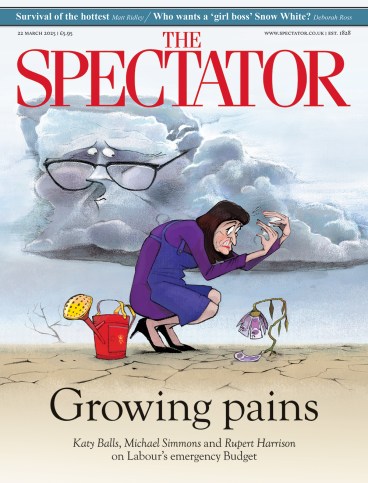

But identifying a problem is not the same as solving it. As Rachel Reeves prepares for the Spring Statement, that reality is weighing heavily on ministers. While next week’s financial update was never meant to be a major event, the deteriorating state of the public finances means it has taken on a new significance. Ministers are nervously waiting for the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) to slash its growth forecast and for rising borrowing costs to have wiped out the Chancellor’s £10 billion of fiscal headroom. ‘We know there is going to be bad news,’ says a government aide.

For a government that claimed its priority was growth and ‘wealth creation’, it is more than a little awkward. Britain is spending beyond its means: the state’s public debt has hit 100 per cent of GDP for the first time since the 1960s. We’re paying more interest on that debt than we spend on education. According to the Adam Smith Institute, 52 per cent of the country is reliant on the state for their livelihood. The left-leaning Resolution Foundation says unemployment figures point to conditions ‘only seen during a recession’.

While Treasury sources insist there won’t be any major tax decisions (though Starmer has refused to rule out extending the income tax threshold freeze that many see as a stealth tax), Reeves will respond by announcing savings. ‘She has a choice – either she does nothing and says it doesn’t matter or she can say there is more we can do to reform the state – headroom or no headroom,’ explains an ally.

While the government’s spending review, led by Chief Secretary to the Treasury Darren Jones, is not due until the summer, ministers are braced for a reduction in day-to-day spending next week. All departments have been asked to find 5 per cent in efficiencies and identify 20 per cent of spending that can be cut. In the Department for Education, officials complain they are having to look for savings of well over £1 billion.

For all the talk of global headwinds, the Chancellor must take her share of the blame

‘Austerity is back,’ says an aide in a non-protected department. Already ministers are in revolt. Tensions worsened in a cabinet meeting this month and the complaints continue. ‘We’re being asked to model cuts that would be unfathomable,’ says a government source. The fact that in the US even Elon Musk is finding it trickier than expected to slash the state shows how hard the task is even with the greatest will in the world.

There’s also the question of whether spending cuts are the right response, or more Treasury groupthink. Andy Haldane, former Bank of England chief economist, recently argued for growth to be taken out of the Treasury’s hands and said ‘further fiscal belt-tightening is impossible to justify’.

Labour MPs complain this is the politics of decline. The party ran on a platform of public investment but is now overseeing £5 billion of welfare cuts, civil service reform and NHS job cuts. They have suggested Reeves change her fiscal rules. ‘There is an element of magic money tree [to their requests],’ complains a Reeves ally. ‘When people say “change the fiscal rules”, they should be called out. If we had done what Germany did last week [loosening the debt break to inject up to €1 trillion in infrastructure and defence], borrowing would be £4 billion higher than the day before and the prison budget would be gone.’

If borrowing is not an option and more tax rises could push businesses to the brink, Reeves’s problem is ultimately one that has plagued successive Tory chancellors: where is the growth? ‘Spoiler: there is no growth,’ replies a government figure.

For all the talk of global headwinds, the Chancellor must take her share of the blame. She cratered business confidence by talking down the economy before raising taxes by £40 billion in her first Budget. For businesses, there was a triple whammy of tax rises, increased minimum wage and changes to workers’ rights. Hikes to the minimum wage risk removing incentives to hire young people (nearly a million of whom are jobless), while the £25 billion national insurance rise for employers will shrink the labour market participation rate. More than half of business leaders say the tax changes will affect recruitment and push up prices.

Did Labour ever have a coherent growth strategy? The Prime Minister remains of the view that his government is more pro-growth than the OBR gives it credit for. Measures such as approving a third runway at Heathrow or stopping legal protections for bats from blocking infrastructure projects don’t help grow the economy immediately but could pay off in the medium term.

‘Too many of us thought not being the Tories would be enough to change things,’ says one MP

But for every promise to demolish a bat tunnel, half the cabinet try to pull Starmer in the opposite direction. ‘Too many of us thought not being the Tories would be enough to change things,’ says one MP. ‘Give trade unions more power because as workers earn more they will spend more… I’m not sure that [growth plan] is working,’ adds a colleague.

Many of the government’s problems began before Labour returned to power. Britain’s public sector has ballooned: the country spends £600 billion on public services yet productivity has not kept pace. Since the start of 2020 inputs from the public sector (money, workers, resources) have climbed 20 per cent, yet outputs have risen by just 12 per cent. If productivity had continued on its pre-pandemic trajectory, the government could be spending £40 billion less annually for the same results.

Other problems are structural. The nature of Britain’s economy means that stagnation abroad quickly causes sclerosis at home. Donald Trump’s tariff war, the OECD warns, could knock 0.3 per cent off global growth and add 0.4 percentage points to inflation.

We already pay four times what Americans do to power factories. Yet Ed Miliband, the Energy Secretary, is still pursuing net zero with zeal. Free-market economists wish Gladstone’s axe would fall on the hundreds of billions of net zero schemes and energy subsidies and let the market find the most efficient solutions. However, even though there are plenty in No. 10 who are sceptical of Miliband, Starmer’s team do not yet see a credible alternative.

Is there a way out of the low-growth trap any time soon? Reeves is expected to go further on civil service and procurement reforms – putting into practice another of Cummings’s obsessions. Many senior Labour figures now share his disdain for a bloated, inflexible Whitehall.

On welfare, Work and Pensions Secretary Liz Kendall has already announced a shake-up. However, the scale of the problem – costs are expected to surge to £10 billion even with the measures in place – means the changes will not be enough.

The third target is the NHS. Data from the Office for National Statistics show NHS productivity is almost 20 per cent below its pre-pandemic peak. While the health quango NHS England is being scrapped, many policy officers remain in place, pushing paperwork. Everything rests on the ability of Wes Streeting, the Health Secretary, to deliver.

Other steps are being considered, including unleashing some of the £2 trillion invested in workplace pension schemes. In her Mansion House speech, Reeves criticised the underuse of pension assets, arguing they should fund British start-ups and infrastructure. Government actuaries point to Australia, where pension funds invest three times more in infrastructure and ten times more in private equity. Meanwhile, the share of workplace pension assets invested in the UK has plunged from around 50 per cent a decade ago to just 20 per cent today. If Britain followed Australia’s example of larger funds, Reeves claims, we could unlock £80 billion in investment which could act as an economic boost. But will it work? Since 2010, US and global markets have outperformed the UK’s – so why would British savers keep more money at home?

The campaign group Looking for Growth will meet this weekend to hear speeches from MPs on how to kickstart the economy. Cummings himself will lead a workshop. The group’s proposed National Priority Infrastructure Bill would slash planning timelines, allowing projects to start within weeks rather than years. The government probably won’t adopt the plan wholesale, but No. 10 has already taken advice on Labour’s own infrastructure bill from its authors.

Even if Labour’s reforms are a step in the right direction, they might make little difference to Reeves’s immediate troubles given the OBR’s verdict is unlikely to be kind to her. The danger, then, is that she becomes trapped by OBR-driven policymaking, tinkering around the edges of the Budget to appease economists rather than looking for permanent fixes.

Tweaks to benefits that seem designed with an OBR abacus in mind and plans that don’t come into effect for years give Labour time to change or even ditch unpopular policies before implementation day. The same can be said of the spending review. Cuts planned for later down the line again allow Reeves to achieve her ‘iron-clad’ commitment to get debt falling in five years’ time, while also giving the government time to reverse those cuts if the economy picks up.

But without growth, things can only get worse. Reeves can fiddle with welfare, Whitehall and the planning system, but the underlying economic reality remains the same. ‘It’s really tough being a Labour government in a time of low growth,’ says a close ally of Starmer. Without a change in fortune, only more difficult choices beckon in the coming years.

Comments