Reader, may I call you John? Now imagine, John, that you are my employer and I know (or claim) that you made an inappropriate sexual advance towards me in the workplace. So I approach you. ‘John,’ I say, ‘you groped me in the lift. Give me £5,000 or I’ll make this public.’

That is blackmail. It’s blackmail whether or not the allegation is true. You can go straight to the police and I will very likely be charged with a serious criminal offence.

Now imagine a different scene. You, John, aware that I have been saying this about you, approach me first. ‘Matthew,’ you say, ‘I know what you’re saying about me. I deny the allegation of course, but I undertake to give you £5,000 if you do not proceed against me, and undertake never to disclose your allegation. Just sign here.’

You have offered me a non-disclosure agreement (NDA). There is no blackmail here — or not, at least, of the criminal kind. Indeed the courts may come to the rescue of either of us if either fails to uphold the agreement (or both of us if a newspaper threatens to break our mutually agreed silence).

What then is the critical distinction between these two scenarios? It can only be that in the first case the potential accuser explicitly made the threat and asked for a deal. In the second the potential accuser (whose threat was implicit) waited for the accused to propose a deal. One is criminal blackmail; the other is a legally enforceable contract.

I fail to see the moral difference between these two cases.

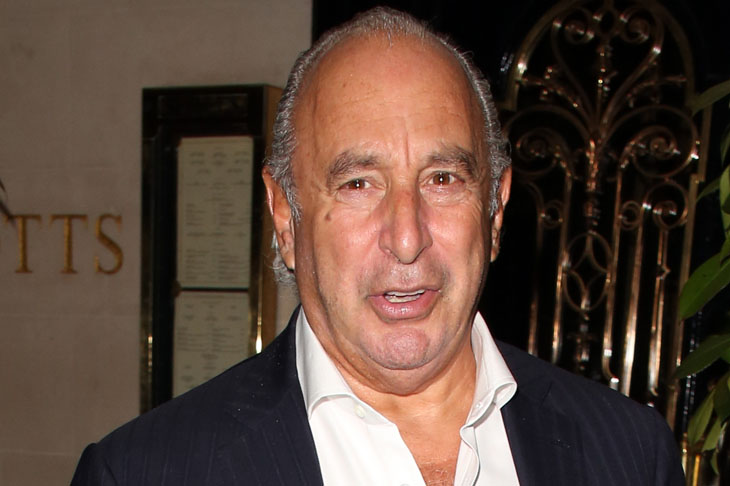

For this reason I’ve found media coverage and comment on the recent controversy over whether the Daily Telegraph could effectively violate NDAs between Sir Philip Green and a handful of aggrieved former employees somewhat skewed.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in