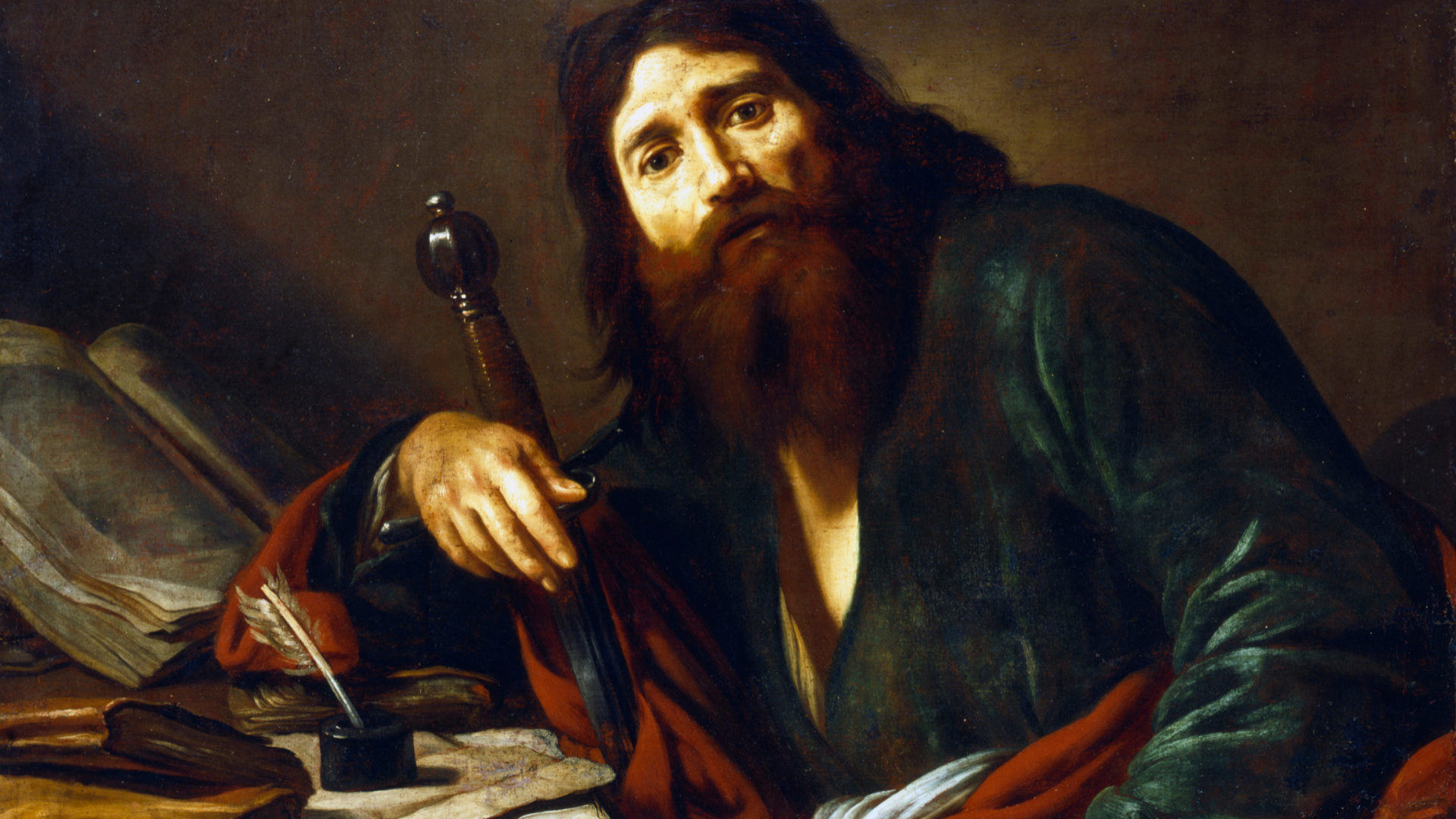

On Easter Saturday, I wrote for the Times about the victimhood of Christ, describing this as a regrettable foundation for a world religion. In online posts beneath my column came hundreds of comments from Christians protesting that I’d misunderstood the Crucifixion’s meaning, which was (they said) the ultimate victory. Triumphantly, Jesus redeemed our sins. Or ‘atoned’ for them. Along with atonement and redemption, expressions like ‘ransomed’, ‘forgiven’, ‘pardoned’, ‘paid for’, ‘healed’ and ‘washed away’ recurred, as well as ‘sacrifice’ – Jesus’s blood-sacrifice to expiate the world’s sins: a kind of reparation. The notion of release – from slavery, debt or imprisonment – suffuses these responses.

In the context of human sin, what do those words actually mean? I’ve been thinking and reading around the subject. In a faithless age many readers will find such exploration arcane. But we remain essentially a Christian country, and over the last week I’ve understood that the doctrine of Redemption through Christ’s crucifixion is central to our national religion; and an outsider’s view – I’m an unbeliever – may be worth setting out.

Christians should face up to this: the whole atonement thing is a terrible muddle

Confronted by the literature, one fast concludes that faith has developed a private language that’s almost impossible for non-believers to understand.

Comments

Join the debate for just $5 for 3 months

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for $5.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just $5 for 3 monthsAlready a subscriber? Log in