The most important thing to know about the filmmaker and writer Marguerite Duras is that she was a total drunk. ‘I became an alcoholic as soon as I started to drink,’ she wrote, proudly. ‘And left everyone else behind.’

It’s not something any of the academics who’d been drafted in to introduce each film in the ICA’s exhaustive Duras season thought to mention, even in passing. Instead they spent their time trying to convince us that her films were political: they were about Palestine, feminism, decolonisation. They aren’t. They’re about being bladdered. They’re about the fact that Duras would wake up by vomiting her first two glasses of booze, before embarking on as many as eight litres of Bordeaux a day.

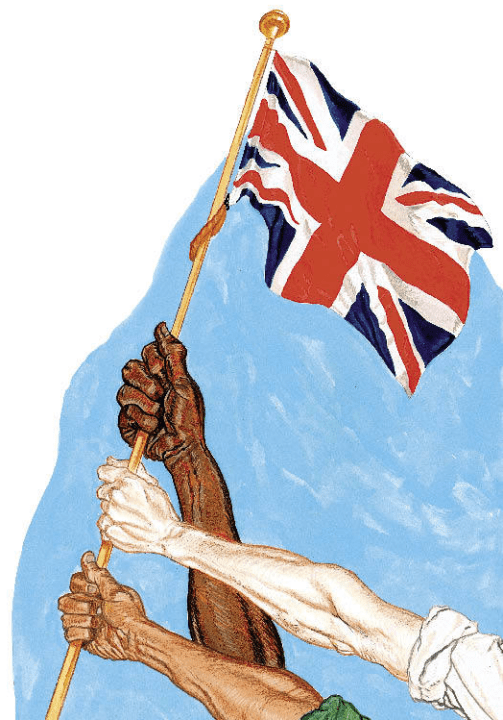

To ruin we all go: cinema and actors, ears, eyes and brain. In the process, a cinema unlike any other forms

Everything about these extraordinarily punishing, borderline sociopathic, but no doubt often astonishing movies begins to make sense once you’re aware of this fact: the non sequiturs, obstinacy, repetition, obliqueness, gloom. The torpor! The films are like an encyclopedia of ways to be lifeless. Characters lounge, loaf, loll, slump. When they can be bothered to stand up, they drag themselves about as if made of lead. The total calories expended by an entire cast of a Duras film could easily be recouped by a small croissant. Of course, no one eats.

In fact, the list of things no one does in the dozen Duras films I saw is impressive. No one drives; no one runs; no one kisses; no one has sex; no one drinks (ha!); no one laughs; barely anyone smiles. There are no jokes (though there is a scene in Nathalie Granger in which Gérard Depardieu attempts to sell a washing machine to two completely uninterested, near-mute witchy types, that is extremely funny), no violence, no deaths. In Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta désert (1976) – one of her most extraordinary – there are no people until the final few minutes. From halfway into L’Homme Atlantique (1981), there are no images.

That’s another thing these films are about: negative form – how to fashion something out of nothing. How to make cinema out of residue. (Far less sexy than politics; much harder to talk about.) Duras’s artistic allies, remember, are not her contemporaries in the French new wave but the prehistoric cave painters and their ‘mains negatives’ stencils, to whom she dedicated a short film.

So what exactly does happen? People talk: mostly in voiceover. They discuss films unmade, fracturing relationships, diplomats gone to seed. A strict independence is maintained between music, script, and visuals, which allows for wild experiments. In Son nom, for example, she explores what might occur if the whole audio of one film, India Song (1975), were grafted onto an entirely new set of visuals to form a sequel. The confusion pushes you to madness, exhaustion, a state of manic bliss. In other words you feel badgered. Eight-litres-of-Bordeaux badgered.

No one could argue the films are enjoyable – just as spending time with someone who’s steaming is not exactly enjoyable. They are, in fact, often deeply boring. But they are a very specific, alluring kind of boring. They’re not boring like Straub-Huillet films are boring. They’re not dry, inept, stingy. They’re boring simply because nothing happens; because the stories are vague; because the camera drifts incredibly slowly over some of the most soporific, if exquisite, images in all cinema, while the same musical riff (a Diabelli variation, Andean pipe music, a tango) repeats and repeats and repeats.

At dusk, a handsome articulated blue lorry, hugging the very top of the screen, cruises past blackly muddy fields in northern France (Le Camion, 1977). We fix on cracks and mansion-house decrepitude in Son nom. We gaze out at the sea from within darkened rooms in Agatha (1981). We watch the blazing sand flats of Normandy in Baxter, Vera Baxter (1977). Underpinning every shot is this touchingly sincere belief – a belief that only ever occurs to the drunk – of the vital importance of staring at things. Of listening to the same piece again and again and again. Of wallowing and getting lost. Of being resolutely unproductive. Of living in the unmade.

Yet stuff is made: there is something monumental, sculptural about the way Duras carves time. It’s like huge chunks of marble are being presented to us, or a series of Barnett Newmans: big blocks of world-building pierced by alien flashes.

So what do we have here? One of the great avant-garde trolls of postwar cinema, no doubt. But also a sensualist whose style sprung from her embrace of being completely plastered for most of her adult life. Not that she didn’t know what she was doing; that she was drunk on the job. But rather that her cinema consciously absorbed the formal patterns and visions that are unique to being paralytic. ‘Let cinema go to its ruin,’ she wrote. And to ruin we all go: cinema and actors, ears, eyes and brain. In the process, a cinema unlike any other forms.

Drunkenness also explains why the planet we inhabit in her films is one where the hours of 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. do not exist. We’re on BST – Blotto Standard Time. Daytime is for nursing hangovers. A unique palette results: the deep blues of dusk, pale greys of predawn, golds of sunrise and sunset. Mysterious, ravishing, punch-drunk colours.

What else does it tell us, this singular amputation of daylight hours? Could this be where the politics of this communist filmmaker becomes most evident? After all, the other curious thing no one ever does in Duras’s films is, well, work.

Comments