It has become fashionable in recent years to talk of the death of liberalism. But as crowds high on the octane of generational self-righteousness rampage through major cities, the evidence mounts. The growing intolerance of freedom of thought, the inability to talk across divides, the way that most of the British establishment, police included, feels the need to pledge fealty to the cause — as though all terrified of ending up on the wrong side — points to a crisis of more than confidence. It is evidence of an underlying morbidity.

Each day the cultural revolution is picking up a pace, with the iconoclasts who attacked the Cenotaph and the statue of Winston Churchill looking for new focuses for their rage. The University of Liverpool has announced that its Gladstone halls of residence will be renamed after protestors pointed out that the former prime minister’s father had owned slaves. So there goes the ‘sins of the father’ ethic too. Nervous broadcasters have started removing programmes ahead of any stampede, with the BBC withdrawing Little Britain and HBO taking out Gone with the Wind from their streaming services in case the woke eye of Sauron flashes on them.

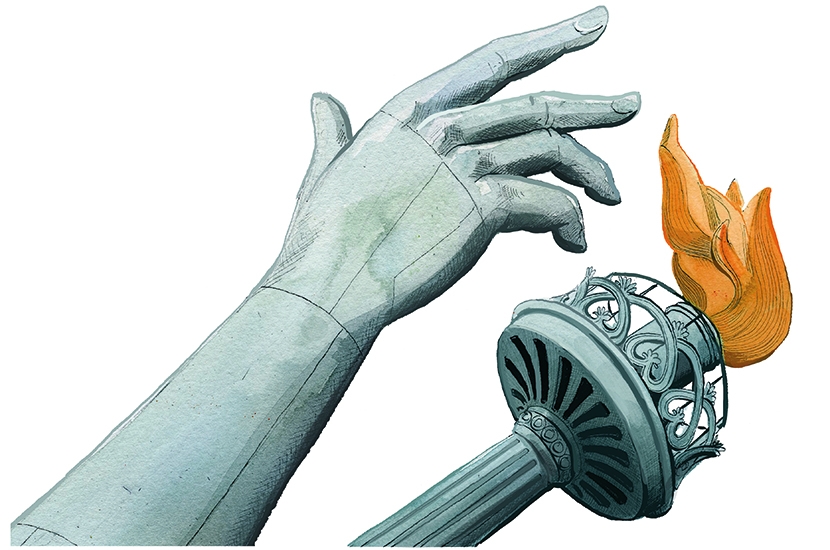

What we are seeing is nothing more or less than the death of the liberal ideal.

Of course ‘liberalism’ was always a broadly defined term; a definition made only vaguer by Americans making it synonymous with ‘left-wing’. But in the truest political sense it encapsulates most of the foundations of our political order, including (though not limited to) equality, the rule of law and freedom — including the freedom of speech that allows good ideas to win out. In the past few years, left-wing critics have been keen to identify what they see as the erasure of liberal democracy by popularly elected leaders on the political right.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in