A few weeks ago, I was wandering with a friend around West London when our conversation turned to the reliable and inexhaustible topic of Morrissey. We were discussing his gestures, in particular when he augments the percussive spondee that opens ‘Sheila Take a Bow’ with two magnificent jabs of his right elbow. So back we went to my friend’s flat to study it again. In goes the DVD; bang go the drums; jab goes the elbow, and my dear friend gives a small cheer of delight, dancing his dance of Rumpelstiltskin glee. ‘Genius!,’ he declares. And he is right.

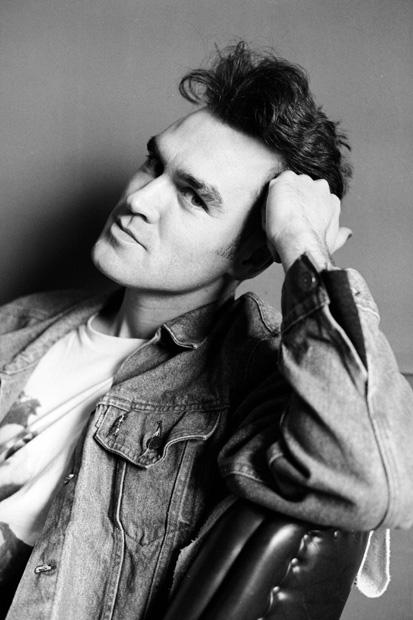

It is a small moment, one of those preposterously arcane details beloved of a devotee of the Smiths, but it somehow seems to say everything about our artistic hero. It is an example of what Morrissey means when he says that, when it comes to music, ‘All we want to see is the sculpted singer — alone, carrying all, sub-plot and sub-text, the physical autobiography.’

The sentence appears in this Autobiography, now finally published as a Penguin Classic. What can a man who places such faith in the revelatory powers of performance and who claims that forming the Smiths was like launching his diary to music, have to say that we cannot already glean from his work? The answer is, a great deal.

Over the course of the book, Morrissey guides us through his childhood in Manchester, his years of unemployment, his tenure as lead singer of the Smiths, and his 26 years as a solo artist. The result isidiosyncratic, uneven, occasionally gauche, sometimes beautiful, tendentious, moving and funny. Morrissey himself exists somewhere on the outer margins of sanity, and has a kind of anti-talent for misfortune and deprivation. ‘You are obsessed with dead people’, his father tells him. ‘He is right of course’, says Morrissey.

The origins of this obsession lie in the impossibly bleak world that was Morrissey’s childhood. Here, family members die at an alarming rate (often in relatives’ spare bedrooms); school ‘offers nothing at all except a lifelong awareness of hate as a general truth’; ‘a journey by car is as unusual as space travel’, ‘prison is an accepted eventuality’, while houses are as depressed as their inhabitants: ‘Nannie’ lives in anticipation of ‘midnight peril’.

Against this there is the unalloyed joy of telly (Miss World being a particular passion: ‘There is no such thing as Mr World, perversely enough’); there is literature (Stevie Smith, Shelagh Delaney, Wilde, Housman, Auden, Betjeman); there is toast (to this day ‘an offer I could never refuse’); there is Mother, ‘never Mum (or the ghastly Manchester “Mam”)’; and there is pop music. T-Rex, David Bowie, Roxy Music, the New York Dolls all offer a picture of another life, and all convince the young Steven Patrick Morrissey that music is the only realm in which anything can happen. And from this conviction, a revelation: ‘If I can barely speak (which is true), then I shall surely sing.’

The journey from this point to the formation of the Smiths was not an easy one, with Morrissey’s chief complaints coming in the form of depression, unemployment and sexual anxiety. At one stage he applies, under duress, for a job as a postman: ‘I am turned down — deemed physically and psychologically incapable of delivering letters.’ But the Smiths did, eventually, happen, and the story that follows is well known. Swift success (inhibited by the spectacular incompetence of Rough Trade’s Geoff Travis), critical acclaim, a heartbreaking split after only five years and then the solo work.

Morrissey handles most of this with pace, wit and a pleasant tone of amused resignation, and he offers some interesting details about his love life (he had one, and it involved men and women). His ability to understand why people might find him ‘a bit much’ (in other words, unbearable) is appealing, as is his willingness to admit he was wrong — even if that only involves upgrading his estimation of a Smiths song from merely good to extremely good.

He is less successful when he attempts a literary flourish and frets about ‘being a writer’. Then his prose becomes laboured, and so opaque as to be meaningless. But when he sticks to writing naturally, he shows true literary talent. His line about Judge John Weeks ‘resembling a pile of untouched sandwiches’ is wonderfully vivid, and he is able to deal movingly with serious subjects while avoiding solemnity.

Morrissey’s themes may be longing, thwartedness, loss, and despair (‘photographs are what we all become’, he says), but they are treated with an irony, tenderness and exuberance that make Autobiography a wonderful accompaniment to the brilliant artistry of the Smiths and their sculpted singer — to the melodies, the elbows and the drums.

Comments