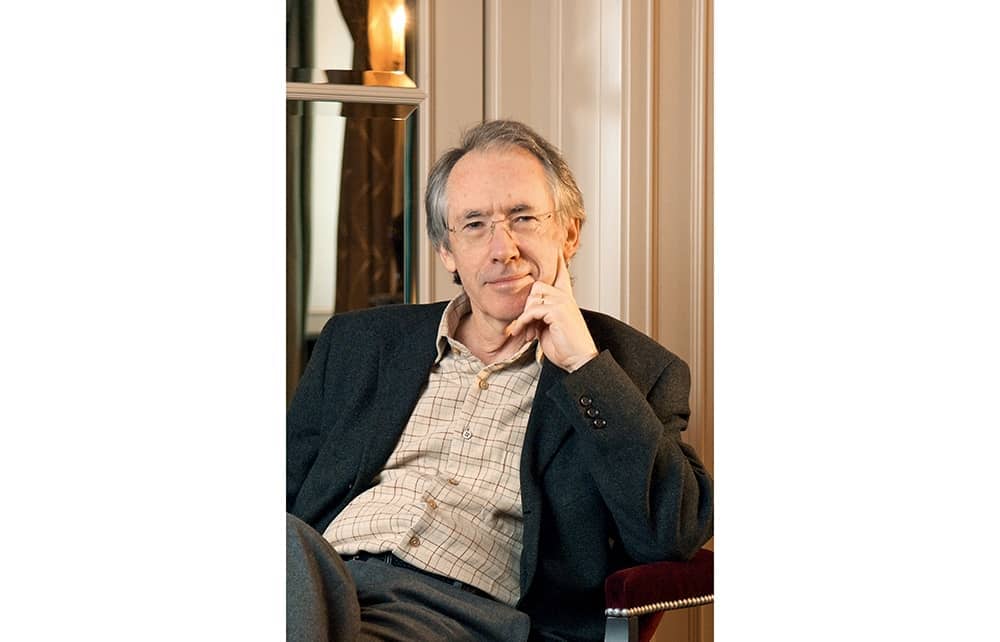

McEwanesque. What would that even mean? The dark psychological instability of The Comfort of Strangers and Enduring Love? The gleeful comedy of Solar and Nutshell? The smart social realism of Saturday and The Children Act? The metafictional games of Atonement and Sweet Tooth? Ian McEwan’s brilliant capacity for reinvention is a hallmark of his literary career.

It’s simpler to say what McEwanesque is not: baggy, meandering, plotless, long. Yet all of these adjectives could be applied to his surprising new novel, Lessons. This cradle-to-grave (well, seven-ish to seventy-something) narrative concerns the life and times of Roland Baines, born, like McEwan, in 1948. Roland shares more than just a birth date with his author. Previous novels have made use of material from McEwan’s own life, but ‘autobiographical’ is another word we don’t associate with his fiction. Lessons represents a sustained and knowing flirtation with that mode.

When the novel opens, Roland is in his late thirties, sitting in an untidy house in Clapham, cradling his infant son.

Get Britain's best politics newsletters

Register to get The Spectator's insight and opinion straight to your inbox. You can then read two free articles each week.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in