Shortly after the war began in September 1939, the branch of the intelligence services called MI8, or the Radio Security Service, recruited H.R. Trevor-Roper (as his name would appear the following year on the title page of his first book, his acerbic and somewhat anti-clerical life of Archbishop Laud). He was a young Oxford don, or would-be don, a research fellow of Merton. His academic career was now interrupted for six years: nominally commissioned in the Life Guards, he plunged deep into the murky world of secret intelligence.

Before that, and before he turned to Modern History, Trevor-Roper had been a brilliant classicist, winning a string of university prizes. He was repelled by what he found the sterility into which classical textual criticism had descended, but it was all the same the brilliant analytical mind he had shown in that field which was now turned to cryptography — other classicists, as well as mathematicians, chess players and musicians displayed a similar aptitude — and to interpreting raw intelligence. Early in the war he and a colleague actually broke one German code, although it must have been a comparatively simple one, before the profound mystery of the Enigma machine.

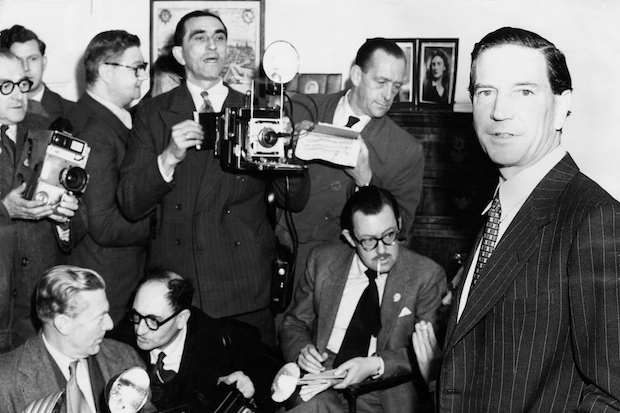

In 1941 he moved to the counter-espionage department of MI6, and in 1943 he was made head of MI6’s radio intelligence section. By this route he became a leading authority on the Abwehr, the German military intelligence service, and its chief, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris. As Trevor-Roper well knew, the Abwehr was both incompetent and disloyal to Hitler in a desultory way; before the end of the war the Abwehr was disbanded, and Canaris was arrested and then executed. It was because of this expertise that Trevor-Roper was commissioned in late 1945 to investigate the death of the Führer. The Allies were much concerned by what proved an illusory threat of German revanchism, and they wanted to establish that death beyond doubt, as Trevor-Roper did in his sparkling, sardonic, bestselling book The Last Days of Hitler.

By the time it was published he had returned as a don to Christ Church, where he had been an undergraduate.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in