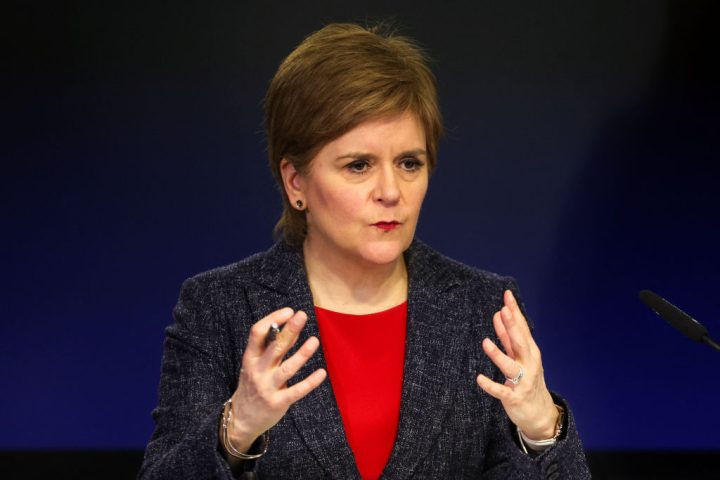

Ministers will come under increased pressure to block Nicola Sturgeon’s gender legislation with the publication of a new Policy Exchange paper today. This examination of the Gender Recognition Reform Bill concludes it will have serious impacts on the rest of the UK.

The Bill removes the safeguards involved in obtaining a gender recognition certificate, the means by which a man can have the law treat him as a woman, and vice versa. It was pushed through the Scottish parliament before Christmas with little time for debate

At present, the law requires an applicant to be 18 or older, to have been diagnosed with gender dysphoria by a clinician and to prove they have lived in their preferred ‘gender identity’ for at least two years. The Sturgeon bill lowers the minimum age to 16, ousts medical experts from the process and requires only three months of living in the preferred gender plus a further three-month reflection period.

If Foran’s analysis is correct, Sturgeon’s bill will fundamentally transform the operation of UK law

The principle underlying it is that a person should only need to self-declare their gender, rather than provide medical evidence, for the law to recognise that gender rather than their biological sex. Supporters say this will make the process more dignified for trans people who consider the need to obtain a medical diagnosis demeaning.

Michael Foran, a Glasgow University law lecturer and author of the Policy Exchange paper, argues that Sturgeon’s legislation will change the operation of UK law. It will alter the definition of ‘sex’ and ‘gender reassignment’ as protected characteristics and allow people who do not suffer from gender dysphoria to change their legal sex. He says it will make it harder to exclude men from spaces that are currently women-only and will give men legally recognised as women a right to be included in female groups and associations. He argues it will give 16 and 17-year-old males with a gender recognition certificate a legal right of admission to girls’ schools and alter the public sector equality duty by redefining who counts as a man or woman.

To most people, including a fair number of government ministers, this will seem pretty recondite and, bluntly, Scotland’s problem. However, Foran warns that changes the bill makes to the operation of UK law ‘will not be confined to Scotland’. As he explains, ‘those possessing Scottish gender recognition certificates who travel to England, Wales or Northern Ireland will have to be legally recognised in their acquired sex’.

Foran also raises the possibility of gender tourism. An English man could obtain a gender recognition certificate in Scotland which would change his gender in England too. This is because ‘biological males possessing a Scottish gender recognition certificate, regardless of where they are in the UK, will be legally female’.

Some critics of the bill say a regime of self-declaration would be open to abuse by bad-faith actors, including men who might self-declare as women to gain access to facilities that are currently women-only. Scottish ministers have countered these concerns by pointing to the statutory declaration applicants are required to make. Making a false declaration can attract a prison sentence of two years.

Foran’s analysis is pretty stark on this question. There has never been a prosecution in the UK for false declaration of gender, even under the current regime with its safeguards. Removing those safeguards as Sturgeon’s new regime proposes to will make prosecution all but impossible. Foran writes:

I cannot see how a criminal conviction could be secured in relation to someone failing to, or not intending to live ‘as a woman’. If woman is a legal status and only a legal status, then living with a [gender recognition certificate] stating you are a woman is living ‘as a woman’.

If Foran’s analysis is correct, Sturgeon’s bill will, firstly, fundamentally transform the operation of UK law; secondly, effectively impose on England, Wales and Northern Ireland legal changes only ever voted for by the Scottish parliament; and, thirdly, will do so with minimal safeguards that may prove wholly unenforceable. This turns the matter into a serious legal and political problem for the Conservative government. Not only would they be forced to accommodate changes in the law that neither they nor the general public support, they face the prospect of being held accountable for the potential consequences of another government’s legislation.

Piling yet more pressure on ministers is the fact that Foran’s paper is introduced by Lord Keen, the former Advocate General for Scotland, who writes:

It would not only be impractical but constitutionally improper for the UK government to permit a devolved legislature to enact a provision that had a material impact upon the operation of the law throughout the United Kingdom.

Foran concludes that this bill meets the requirements for a Section 35 order. This is a provision of the Scotland Act that allows ministers to prevent any Holyrood bill that adversely affects the operation of reserved law from being presented for Royal Assent. The Scottish government would inevitably seek judicial review. In all likelihood, we would be on course for another Holyrood-versus-Westminster showdown at the Supreme Court.

I’m not a lawyer but Foran’s arguments seem straightforward and compelling. The decision whether to issue a Section 35 order is at least as much about politics as law. From a political standpoint, I cannot see how ministers can possibly avoid it. Sturgeon’s bill is too sweeping, the potential fallout too significant, and the issues at stake too fraught. Failing to make a Section 35 order might be as rash and reckless as the legislation in question.

The UK government is meant to govern the whole UK and to protect the rights, interests and safety of everyone living there. To allow the Scottish parliament to impose its will past Gretna Green, especially on such a controversial subject, would be an abdication of ministers’ duty to the country. There is no way around it. Section 35 it will have to be.

Comments