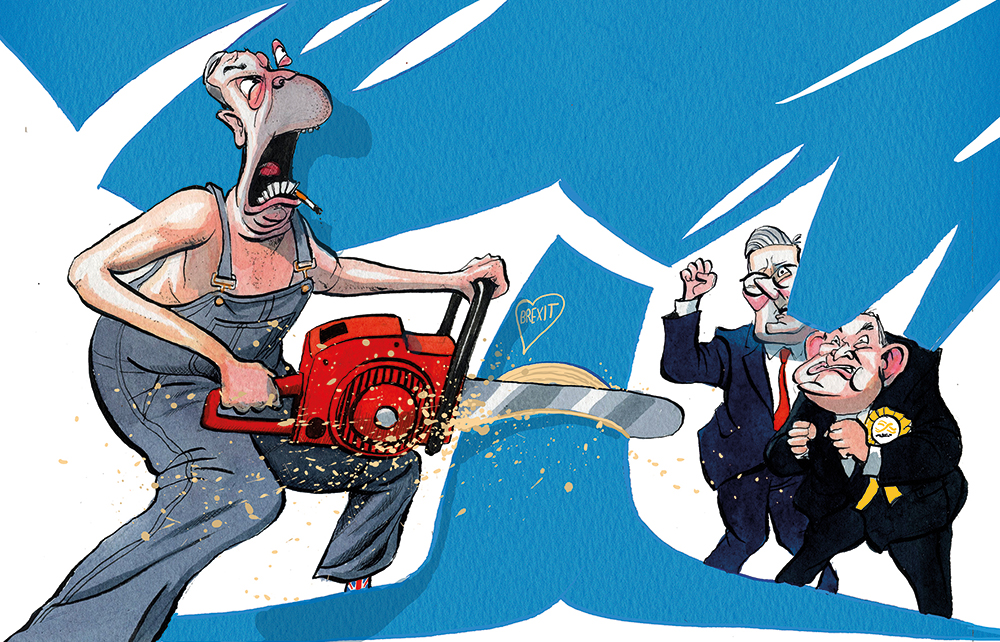

Nigel Farage is about to turn British politics upside-down for a third time. His Ukip insurgency forced the Tories to offer the 2016 referendum on the EU and changed history. When his Brexit party pushed Tories into fifth place in our last-ever European parliament elections in 2019, his victory established him as the most effective Tory-slaying machine ever deployed in political battle. If Keir Starmer or Ed Davey could have had one wish before the election, it would have been for Farage to return and attack the Tories, so they could sit back to watch the right eat itself.

‘Farage has become our patron saint,’ says one Lib Dem strategist

So it has proved. Some opinion polls say the Conservatives could be looking at as few as 50 seats, perhaps fewer than the Liberal Democrats. Starmer is believed to be on course for about 450 seats and a majority so large that he could remove the whip from any rebel who defies him and still exert an easy control over parliament. He has started talking about a ‘decade of renewal’, which shows how he is thinking: thanks to Farage’s Tory-felling, Labour is looking at ten years of power.

‘Vote Reform, get reform,’ said Richard Tice, who was the party’s leader until Farage replaced him earlier last month. But polls suggest that even if 17 per cent of voters back Reform, the party will end up with just three seats. This is unfair, but the Westminster system is designed to be unfair. Whatever his intention, Farage has ended up serving as a purely destructive force. He has become the nemesis, not the rejuvenator, of the causes he purports to care about.

The Reform UK manifesto looks like a souped-up Conservative pledge card: NHS reform, lower tax, immigration control, ditching net-zero targets, banning ‘transgender ideo-logy’ in schools, replacing HS2. Reform wants to offer conservatism without Conservatives. But its effect will be to halve the number of MPs in parliament to promote these causes. That’s the paradox.

Both Starmer and Davey have had lacklustre campaigns. Starmer has achieved his goal of saying nothing of interest. His personal approval ratings are almost as low as Gordon Brown’s in his final days. Davey has spent his time providing light amusement for the television news by falling off waterboards and tightropes and giving CPR to dummies. Meanwhile, Farage has been giving CPR to the Liberal Democrats in seats they would never be able to win on their own.

Take Surrey: ten of its 12 constituencies are in play for the Lib Dems. The same is true in Cornwall and much of the southwest. Boris Johnson’s old seat of Henley may fall to Davey’s astonished troops and perhaps even Tunbridge Wells, which has been Tory for more than a century. Salisbury, Tory since 1924, is now predicted to go Lib Dem. ‘Farage has become our patron saint,’ says one Lib Dem strategist. ‘He can do more for our chances than we can. Our guys should really dress up as his and campaign for Reform.’

What about the argument that Reform’s election campaign is not really about Westminster seats but about purging and steering the Tory party? That voting Reform will make the Tories more radical, more Nigel-esque, more committed to principles of lower tax and small government? A template is waiting in the ‘popular Conservatism’ advocated by Liz Truss, Jacob Rees-Mogg and Suella Braverman. If Farage were really interested in building something new, he might have decided not to put candidates against right-wing Conservatives. Why weaken the cause?

But there is no real cause this time: just the schadenfreude of inflicting the damage. Braverman once called for Farage to ‘be welcomed’ by the Conservatives, but her formerly safe seat has become a four-way marginal thanks to Reform. Rees-Mogg went so far as to suggest that Farage could be made a minister in a Conservative government, but his comments haven’t spared him. Polls predict he will lose to Labour in the newly created North East Somerset and Hanham. This is thanks to a challenge by the Reform candidate Paul MacDonnell, a self-styled libertarian trying to unseat Rees-Mogg on the grounds that the Conservatives have become a ‘destructive left-wing organisation’.

When Rees-Mogg is being attacked as a sleeper for the left, we can see that Reform does not represent a coherent strategy or political philosophy but something entirely new and rather extraordinary: a party that exists merely to subvert rather than to promote its own cause. This is even dawning on a few Reform activists. One, Charlie Thompson, has pulled out of the election saying that he realised he would end up helping Labour replace Simon Clarke, a former Tory minister and low-tax Brexiteer. Reform UK was furious and has backed Rod Liddle, who’s running for the Social Democratic party (see his article).

Tom Wellings, a lawyer, was due to stand for Reform against Gavin Williamson, the former education secretary, but stood down once he realised he would pave the way for a Labour MP. ‘This is a matter of deep concern to me and should be to anyone who supports the policies and agenda of Reform UK,’ he said. Lee Anderson, the former Conservative deputy chairman, used to warn that a vote for Reform helps Labour – before he was thrown out of the party and defected to Reform. He now says he won’t actively campaign against certain Tories, but there aren’t many others showing such restraint in his new party.

Farage’s argument is that he’s playing the first part of a long-term game: destroy, then rebuild

It’s not hard to see what happens next. If the polls are right and Starmer ends up with a majority out of all proportion to his support, he will be urged to use this freak moment of power to make the political landscape more favourable to the left, just as the Thatcher revolution promoted home ownership, share ownership and other causes more favourable to the right when the SDP split the left in the 1980s. ‘Why would Starmer sit there and wait for the right to recover?’ asks one Tory minister. ‘He’ll do what we did.’

State regulation of the press could be forced through, stifling commentary that challenges the government. Labour will be able to renew the BBC Charter and appoint a more muscular head of Ofcom. GB News, the television channel where Farage and Rees-Mogg are both presenters, may end up being taken off air. Online-debate rules could be tightened to make it harder to publish against-the-grain views. And who in the Commons would be there to protest such a crackdown?

A crushing majority will make it easier for Starmer to water down Brexit. He can sign Britain up to various regulatory schemes, taking it back into the EU’s orbit while stopping short of rejoining. Not a single member of Starmer’s front bench backed Brexit, so his team is unlikely to seek new trade deals to make Brexit work. All of this will be far more straightforward because Farage will have done so much to clear away the MPs who would have opposed it.

Farage’s argument is that he’s playing the first part of a long-term game: destroy, then rebuild. The destruction part, of course, happens now and the creation will take five to ten years – perhaps longer. When Canada’s Reform party smashed the country’s conservatives in 1993 (reducing them to two lonely MPs), it took almost 13 years to recover. And that’s assuming lots of patience from Farage, who was only recently saying he wouldn’t stand for Clacton because he thought America’s election mattered more than ours.

His claim last month was that he was needed to help Donald Trump ‘stop World War 3’ – a phrase popular with Trump supporters and usually code for letting Vladimir Putin flatten Ukraine. Farage tried this patter a week or so ago, saying that Putin was ‘provoked’ into invading by Ukrainians who sought closer allegiances with the West. These are Trump-style tactics: say something outrageous, so people talk about you for days. But his comments led to the first dent in Farage’s poll rating, suggesting that his Putin-sympathising language is backfiring.

Or it might suggest something else. That those who want a better use of Brexit powers, NHS reform, lower tax and immigration control are starting to realise they are about to enable a mass suicide of the right. The only hope left for those around Sunak is that Reform supporters will, in the end, stop short. They just can’t hate the Tories that much. Can they?

This article is free to read

To unlock more articles, subscribe to get 3 months of unlimited access for just $5

Comments

Join the debate for just $5 for 3 months

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for $5.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just $5 for 3 monthsAlready a subscriber? Log in