‘Of all the things I’ve drawn,’ Michael Craig-Martin reflects, ‘to me chairs are one of the most interesting.’ We are sitting in his light-filled apartment above London, the towers of the City rising around us, and we are discussing a profound question, namely, what makes an object a certain type of thing? Or to put it another way, what makes a chair a chair?

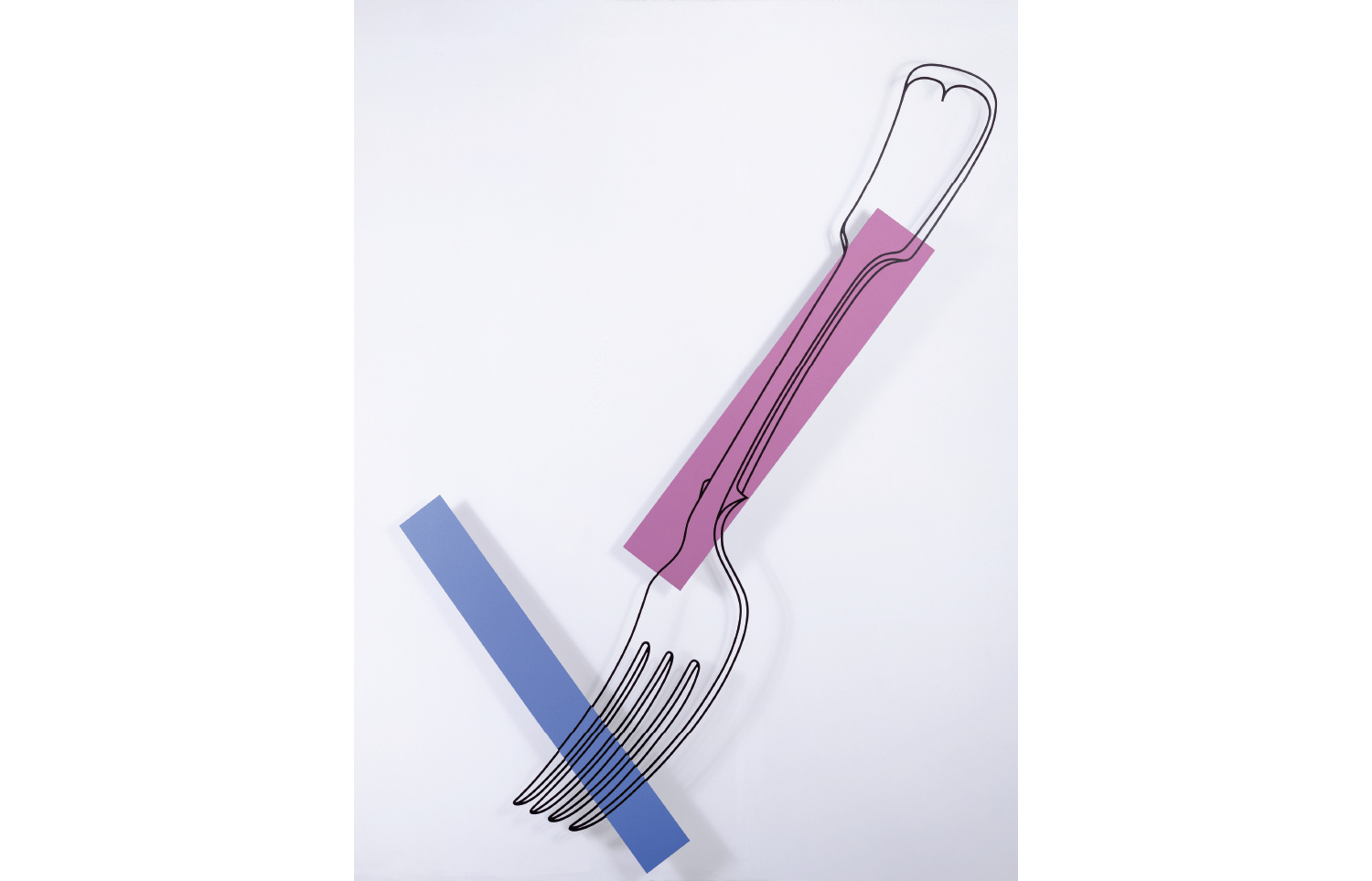

Craig-Martin’s career has been characterised by what he calls ‘my object obsession’. There will be chairs on view in the grand retrospective of his work which is about to open at the Royal Academy, but by no means only chairs. The galleries will be filled by a cavalcade of mundane bits and pieces, among them safety pins, filing cabinets, forks, smartphones, pliers, light bulbs and buckets. All of these are drawn with a thick, clear black line and painted in vivid, joyous and completely non-naturalistic colours.

‘I changed a glass of water into a full-grown oak tree without altering the accidents of the glass of water’

Craig-Martin could be categorised as a highly individual variety of still life artist. And still life is a genre that leads artists to muse on the nature of things, from Zurbaran in the 17th century to Picasso and Braque in their cubist phase. This brings us back to the chair-ness of chairs.

‘Chairs,’ he goes on, ‘have been made out of every material you can think of – metal, wood, plastic, rubber, cloth, cork. They’ve come in an incredible number of forms and designs. And yet a chair is a chair and every one of them is rightly called a chair.’

I faintly recall encountering this conundrum many years ago as a first year philosophy undergraduate, writing an essay on ‘the problem of universals’. This involved puzzles such as ‘what makes a chair identifiable as a chair even though it looks different from all the other chairs?’.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in