Sir Keir Starmer and the Labour front bench are increasingly candid about their plans to ‘recalibrate’ Britain’s relationship with the EU within 18 months of entering Downing Street. Trade barriers with the EU would be lowered, regular EU-UK summits would be held at permanent official and ministerial level, a return to the Dublin Agreement on migration would be negotiated. They would also sign a UK-EU security pact.

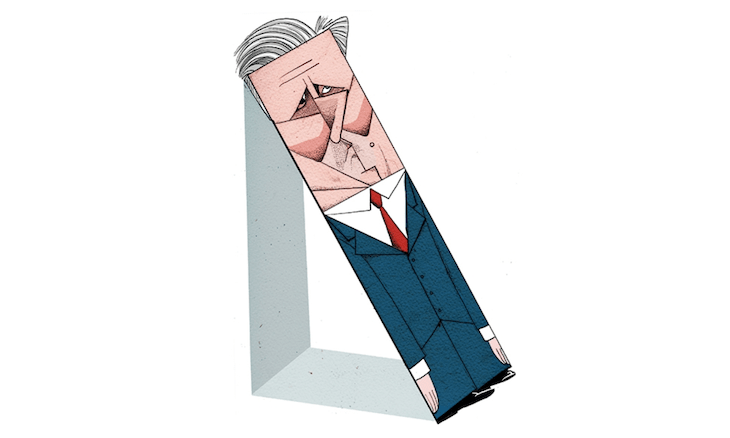

The Labour leader insists he is not promising to return the UK to the single market or the customs union. But the fear is that a novice, naïve and inexperienced Labour government would be putty in the hands of Euro-maximalist leaders of the calibre of Emmanuel Macron, seconded by the dour, grinding, legalistic and battle-hardened negotiators in the Brussels bureaucracy.

A new and inexperienced Labour administration could end up frittering away the UK’s most powerful bargaining chip

Moreover, a minority Labour government propped up by the Europhile Lib-Dems would be a godsend to Brussels. One has to ask what the EU will demand in any renegotiation?

Far from rejecting renegotiation of the Brexit deal, Brussels – while feigning refusal – will welcome it for two reasons. Firstly, the new Labour government would be the ones coming begging bowl in hand. Secondly, the present deal brokered in 2020 excludes a vital coveted area for Brussels: a defence and security pact with what is arguably Europe’s most forceful defence power, as evidenced by the UK’s leading political and military support for Ukraine.

But in their enthusiasm for a new deal, Labour will soon discover the hard reality that Macron and Brussels have their own plans for the UK. Given the bitterness of the Brexit negotiations and the Anglo-scepticism of the Brussels bureaucracy, EU demands will be robust and hardline. Indeed some aspects of their vision are hidden in plain sight and are already being implemented by Rishi Sunak’s government, a gift to Labour in legitimising their own plans.

The overarching framework for what the EU considers a renewed relationship with the United Kingdom is the European Political Community (EPC). The brainchild of France’s president Macron, he announced it to the European Parliament on 9 May 2022. British media made little of the Macron plan, nor of its prominence in the official communiqué of the recent Sunak-Macron summit. Yet it is potentially a major change to the architecture of European international relations. It has the potential, progressively and surreptitiously, to enmesh Britain anew in EU rules, regulations and procedures, notably in defence and security.

It is often forgotten that the European continent and the EU are not the same thing; the former comprises 44 sovereign states, the latter 27. The geopolitically attuned Macron regrets this:

‘The EU, given its level of integration and ambition, cannot in the short term be the only way to structure the European continent.’

For Britain, the ‘in the short term’ is a warning of how the EPC is likely to evolve. The EPC was approved in Brussels last June ‘to foster political dialogue and cooperation to address issues of common interest so as to strengthen the security, stability and prosperity of the European continent’.

Then-prime minister Liz Truss agreed to join, but was wary of the EPC’s aims. She insisted, according to Le Monde, that the EPC bear no resemblance to EU institutions, that there be no permanent secretariat or fixed structure and that it merely be a forum for political dialogue. More than 40 members attended the first meeting in the Czech Republic on 6 October, including the UK, Turkey and Ukraine. The next meeting is scheduled for Britain in June 2024.

But the EPC is merely a stepping stone to Brussels’s true requirement from London: a legally-binding commitment to an EU common defence union. That would commit Britain to the recently launched European Defence Agency, EU defence standards and procurement and the EU coordinated annual review of defence, leading to greater competition with Nato. Labour’s call for a UK-EU security pact, rather than a loose security agreement, is music to the ears of the EU and Macron.

French diplomats have been playing down the suggestion that the EPC is an EU-plus-plus club and playing up its inter-governmental nature. If the EPC remains a mere continent-wide intergovernmental talking shop that does not seek to elbow out Nato then it could serve UK interests.

A new and inexperienced Labour administration could, however, easily end up frittering away the UK’s most powerful bargaining chip with the EU, its defence and security dimension, for little return on reducing present day post-Brexit friction. Worse still, Britain could find itself constrained and committed in that most vital of sovereignty areas that did not even figure pre-Brexit: defence and security.

Comments