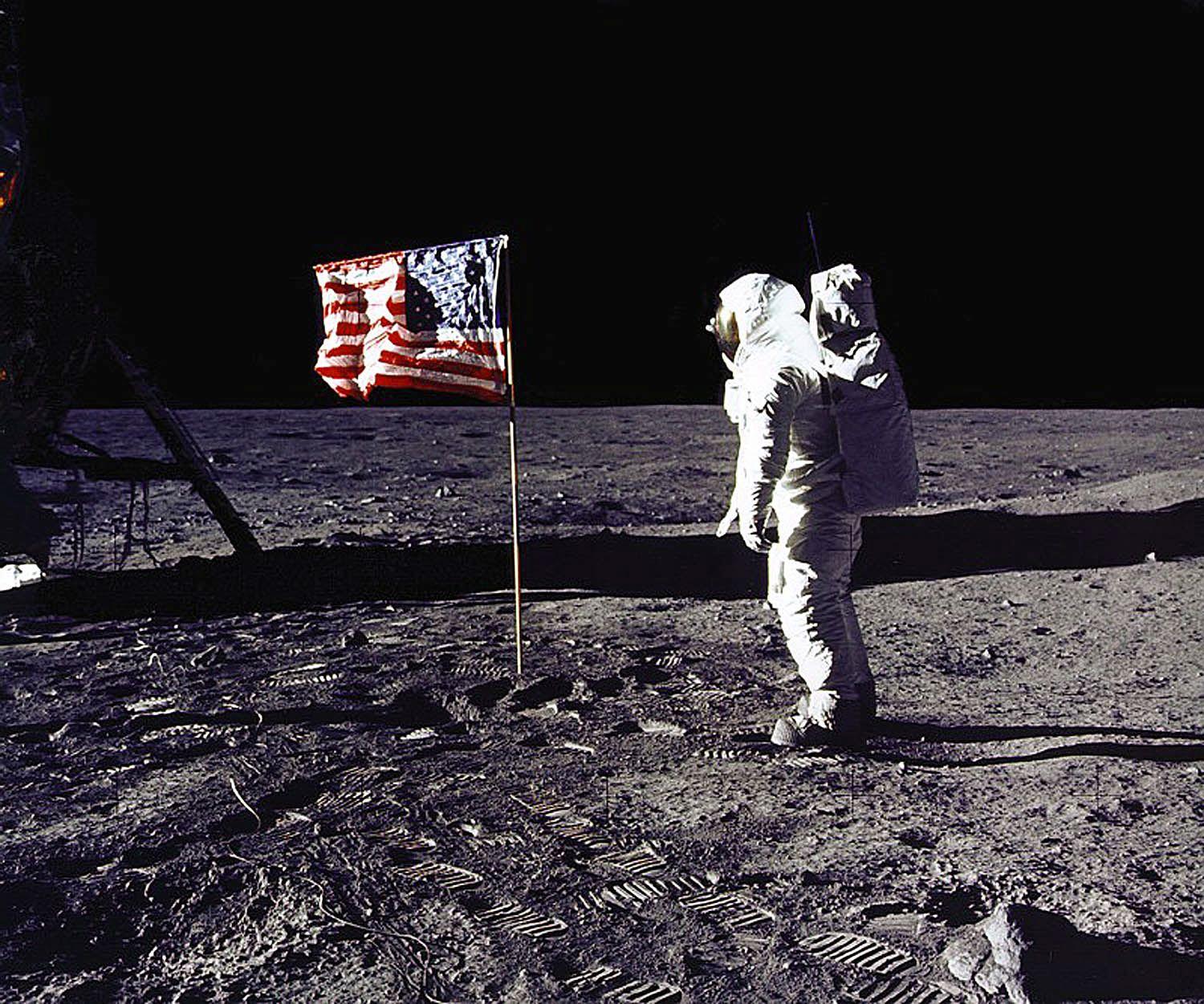

I’m old enough to have viewed the grainy TV images of the first Moon landings by Apollo 11 in 1969. I can never look at the Moon without recalling Neil Armstrong’s ‘One small step for a man; one giant leap for mankind’. It seems even more heroic in retrospect, considering how they depended on primitive computing and untested equipment.

Once the race to the Moon was won, there was no motivation for continuing with the space race and the gargantuan costs involved. No human since 1972 has travelled more than a few hundred miles from the Earth. Hundreds have ventured into space, but they have done no more than circle the Earth in low orbit. In the mid-1960s, Nasa absorbed 4 per cent of the US federal budget; today it’s 0.6 per cent. If that momentum had been maintained, there would surely be footprints on Mars by now.

Space technology has, nonetheless, burgeoned in the past four decades. We depend routinely on thousands of orbiting satellites for communication, navigation, environmental monitoring, surveillance and weather forecasting. Space telescopes orbiting far above the Earth’s atmosphere have beamed back images from the remotest cosmos. They have surveyed the sky in infrared, UV, X-ray, and gamma ray bands that don’t penetrate the atmosphere and therefore can’t be observed from the ground. They have revealed evidence for black holes and have probed the ‘afterglow of creation’ – the microwaves pervading all space, whose properties hold clues to the very beginning, when the entire observable cosmos was squeezed to microscopic size.

Of more immediate public appeal are the findings from spacecraft that have journeyed to all the planets of the solar system. Nasa’s New Horizons beamed back amazing pictures from Pluto, 12,000 times farther away than the Moon. The European Space Agency’s Rosetta landed a robot on a comet.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in