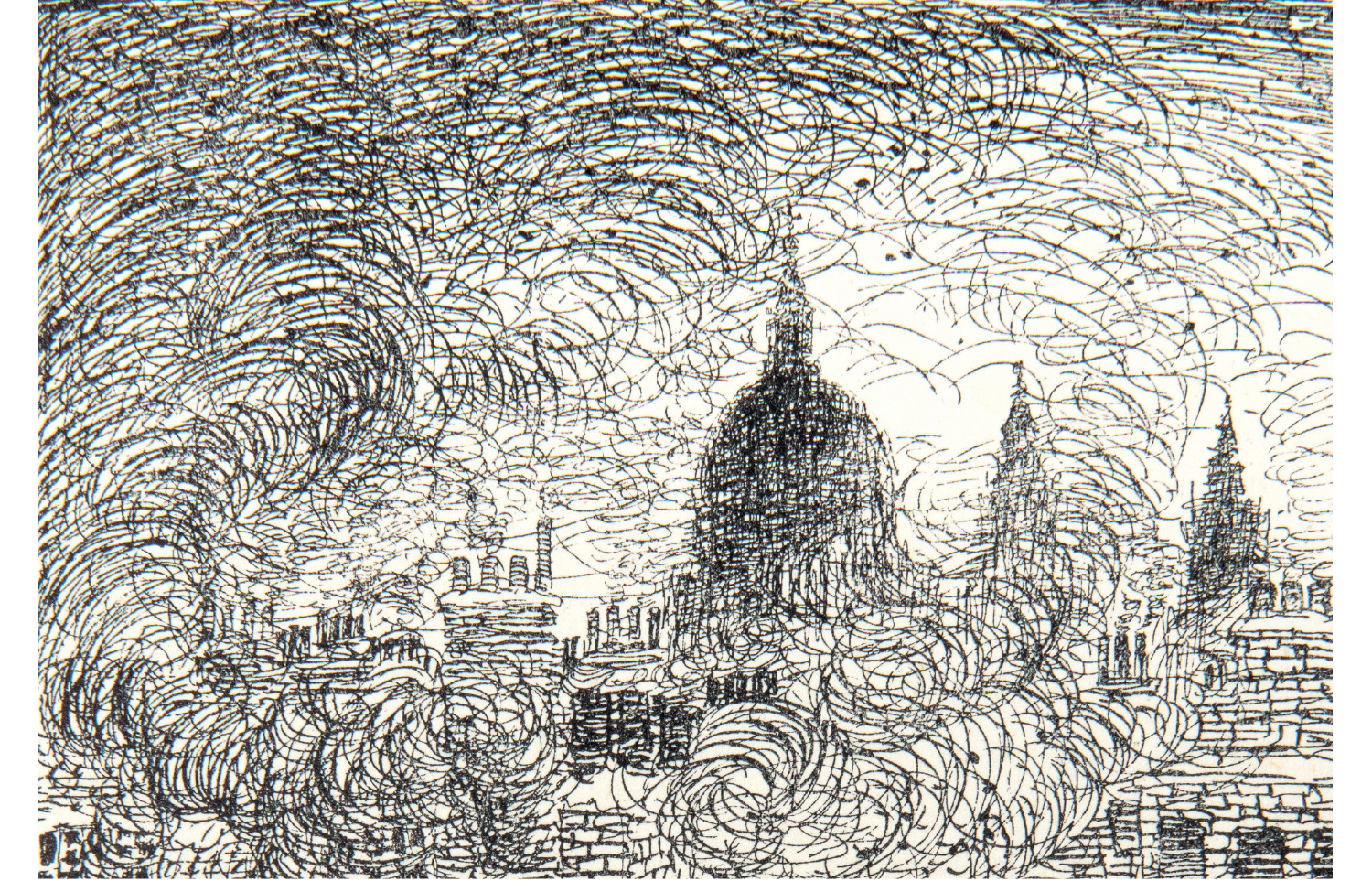

Conjure up before your mind a vision of ‘Dickensian’ London, and as likely as not you will see in your imagination a street filled with yellow fog, dimly illuminated by a gas-lit street lamp. The classic ‘pea-souper’ was caused by a natural winter fog in the Thames basin, turned yellow by the coal fires and industrial chimneys of the Victorian city and held in place for days by the phenomenon of ‘temperature inversion’, when a layer of warmer air traps the cold, damp and increasingly impenetrable atmospheric mix in the streets below.

Charles Dickens was probably more responsible than anyone else for the association: most famously, of course, in the opening scene of Bleak House (1853), where he uses fog as a metaphor for the legal obfuscation caused by the Court of Chancery:

Fog everywhere. Fog up the river, where it flows among green aits and meadows; fog down the river, where it rolls defiled among the tiers of shipping and the waterside pollutions of a great (and dirty) city. Fog on the Essex marshes, fog on the Kentish heights. Fog creeping into the cabooses of collier-brigs; fog lying out on the yards, and hovering in the rigging of great ships; fog drooping on the gunwales of barges and small boats…[and] at the very heart of the fog, sits the Lord High Chancellor in his High Court of Chancery.

But Dickens made metaphorical use of London fog in other novels too. In his last completed work, Our Mutual Friend (1865), for example, it stands for the corrupting influence of money that lies at the heart of the City:

It was a foggy day in London, and the fog was heavy and dark… Even in the surrounding country it was a foggy day, but there the fog was grey, whereas in London it was, at about the boundary line, dark yellow, and a little within it brown, and then browner, and then browner, until at the heart of the City – which call Saint Mary Axe – it was rusty-black.

As the journalist and bestselling travel writer Henry Vollam Morton wrote in one of his most popular books, In Search of London (1951): ‘Charles Dickens has done more than any writer to create and perpetuate a picture of early Victorian London, with its fogs, its filth and squalor.’

The Charles Dickens Museum has brought this association to the fore in its latest exhibition A Great and Dirty City: Dickens and the London Fog. Held in Dickens’s own home in Doughty Street, on the 150th anniversary of one of the most persistent and destructive fogs of the Victorian era, a fog so dense that it asphyxiated a number of prize animals at the annual Smithfield Cattle Show, it reveals the dilemma facing Londoners at the time, and for long afterwards. On the one hand, the dangers not just to health but also to the physical fabric of the city were widely recognised. It left many buildings blackened and often caused serious damage to the bricks themselves, the damp and sulphurous emissions eating into them. Materials such as silks could be ruined by the soot. Business was affected too. An article in Dickens’s journal, Household Words, written by W.H. Wills, Dickens’s sub-editor, highlights this when a merchant called Mr Broadelle recounts that a December fog ‘got into the white satins’, ruining one ‘hundred pounds’ worth of stock and causing them to be stained black: it ‘put them into an ugly, foxy, unsaleable half-mourning’.

On the other, Londoners were reluctant to consent to any kind of effective smoke-abatement measures. An article by an anonymous author that appeared in Household Words in 1854, displayed in the exhibition under the title ‘Smoke or no Smoke’, challenged the effectiveness of a Smoke Abatement Act steered through parliament by Lord Palmerston, pointing to the fact that although the act attempted to reduce the dirty air from industrial chimneys, it did nothing to curb the increasing amount of smoke from domestic chimneys as the population of London grew.

For many Londoners, including Dickens himself, keeping the home fires burning was an essential symbol of family and domestic life as well as a necessity on cold winter evenings. Visitors to the exhibition can view the hearthstone laid by Dickens in front of the fireplace in the drawing room, as well as the coal chute down which deliveries were poured from a horse-drawn dray into the coal cellar under Doughty Street. There is even Dickens’s own fire poker from the dining room at Gad’s Hill Place, his home from 1856 until his death in 1870. A coal fire was an unavoidable part of the family home at this time: there were no real alternatives to the smoke-producing coal used to heat homes and to cook. Coal merchants made matters worse by exporting the best-quality coal to increase profits, leaving the cheapest and most polluting for domestic consumption. Lord Palmerston’s act was one of many passed to clear up London’s air, but real change could come only when cleaner technology, such as gas and electricity, became cheap enough to provide viable alternatives for all.

Londoners even felt some affection for their fogs. They were a kind of emblem of the city. Long after they disappeared in the mid-20th century, tourists still arrived in London expecting it to be foggy. As a kind of substitute, they could go to a souvenir shop and buy a can of ‘genuine London fog’. Nicknames testified to Londoners’ feelings: a fog was not only a ‘pea-souper’ (named after the yellow split-pea soup that was the food of the poor) but also ‘London particular’, another name for a mistress, perhaps hinting that Londoners felt as ambivalent about fog as some married men may have felt about their extramarital affairs. It was also the name of a popular brown Madeira wine solely imported for the London market.

Fog represented London’s success – industry pumping out smoke because it was providing employment; and domestic chimneys belching out black smoke symbolising family prosperity and wellbeing. Smoke abatement did not please everybody. As late as 1945, George Orwell could be found complaining in the Evening Standard of a ‘noisy minority [who] will want to do away with the old-fashioned coal fire’ adding that the great virtue of a coal fire is that it ‘forces people to group themselves in a sociable way’.

Charles Dickens was not the first to highlight the fogs of London – even Queen Elizabeth I had complained of London’s dirty air in the 16th century, and the diarist John Evelyn denounced it in his Fumifugium in the 17th – but Dickens was the first to engage with the phenomenon in an imaginative way. He understood that the fogs were a mixture of the natural fog that was part of London’s damp atmosphere and the man-made soot and smoke from London’s ever-increasing chimneys. At the time he wrote, the city’s urban and industrial growth was still increasing the frequency and severity of London fogs, which reached their apogee in the 1880s, well after the novelist’s death.

As a kind of substitute, tourists could go to a souvenir shop and buy a can of ‘genuine London fog’

Dickens set a trend for seeing London fog as a part of London’s brand, and most writers who followed him also explored its potential. Pea-soupers play a key role in London novels as varied as Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady (1881), Stephenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent – which, though published in 1907, is set at the height of the fog years, in 1886 – and John Galsworthy’s The Forsyte Saga.

There have been exhibitions of these literary responses to London fog in the past, and this one at the Charles Dickens Museum illustrates how the major literary engagement with the fog began with the great writer, who, as in so many things, led the way. Perhaps in the future an exhibition space can put them all together and show the changing treatment of London fog as an image up to contemporary times and the various attempts to clean London’s air. The great pea-soupers may be a thing of the past, finally conquered by the Clean Air Act of 1956, but today Londoners are facing a newer, less obvious but no less dangerous variety of atmospheric pollution in the form of hydrocarbon emissions from petrol- and diesel-powered motor vehicles.

A Great and Dirty City: Dickens and the London Fog is at the Charles Dickens Museum until 22 October.

Comments