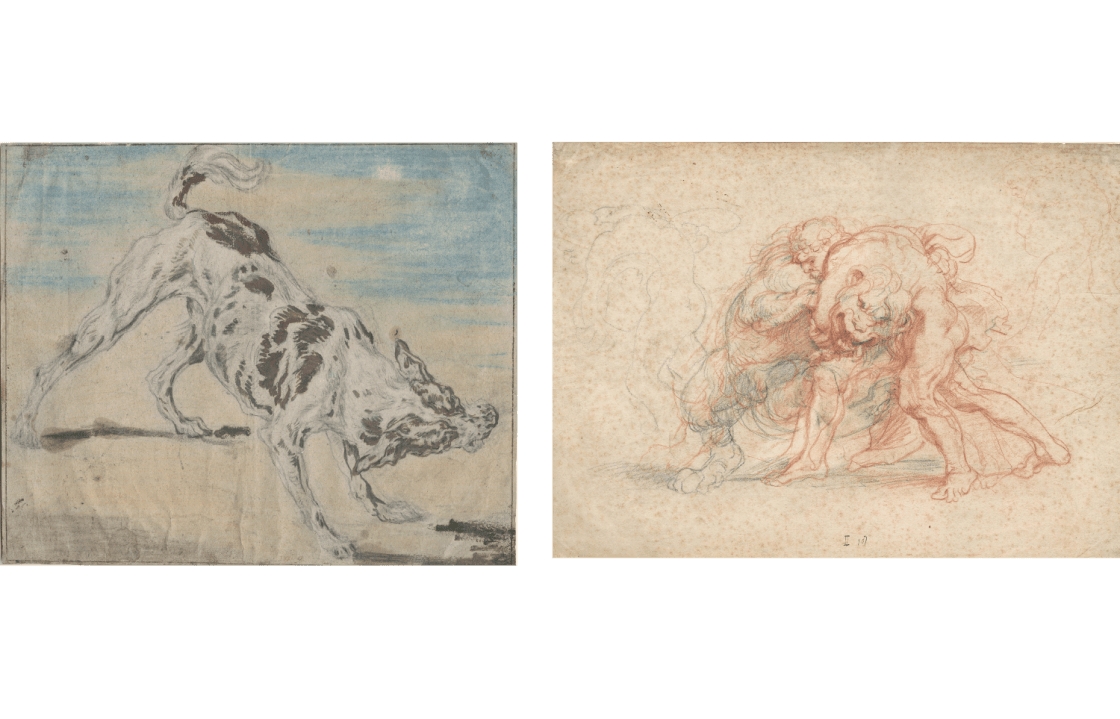

The term drawing is a broad umbrella, so in an exhibition of 120 works it helps to outline some distinctions. A good place to start is to ask what drawings are for, and that is what Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum has done with its current show of sketches by Flemish masters – staged in collaboration with Antwerp’s Museum Plantin-Moretus – dividing them into studies, designs and stand-alone finished works.

Van Dyck’s teenage studies are a measure of how flabby our ideas of draughtsmanship have become

If you’ve ever had the chance to visit it, you’ll know what a special place the Plantin-Moretus is. Still occupying the original premises in which it was founded as a printworks in the 16th century, it sits on a hoard of drawings by the great names of Flemish art dating back to a time when Antwerp was at the centre of a booming trade in prints, metalwork, stained glass and tapestry, all of which began with drawings on paper. The design section features drawings of breath-taking intricacy – the world of interiors can never have witnessed towel racks more spectacular than those designed by Paul Vredeman de Vries – but for lovers of drawing rather than design, the studies and stand-alone works are this show’s most exciting attraction.

The teenage prodigy Anthony van Dyck’s astonishing ink and wash study for his first public commission, ‘The Carrying of the Cross’ (c.1617-18) – even allowing for his use of the Tipp-Ex of the day to make corrections – is a measure of how flabby our ideas of draughtsmanship have become. In life classes today, where they’re still taught, students learn how the human body moves under its clothes; in Van Dyck’s day they worked out how it moves under its skin. Forget those cute little wooden jointed artists’ mannequins; to delineate the calf muscles in this drawing, the young Van Dyck will have used a statuette of a flayed human corpse – unless, that is, Rubens let his star assistant borrow his anatomy book of drawings of skinless bodies.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in