For generations, humankind has been focused on its terrestrial environment; shaping it through agriculture, urbanisation and conservation. Our aquatic environment, meanwhile, has been a comparatively unmanaged source of food, enabled transport, and is a location for leisure. It has also absorbed much of our CO2 production and been a repository of our waste from land. In recent years, we’ve demanded even more of it: a place for low carbon energy generation, a mine of rare minerals, and a site for commercial development.

The cost of that use – over-use – is increasingly clear when we consider the loss of biodiversity, reduced fish catches, degraded environments and increased pollution, particularly plastics. We also see the impact of climate change gases in the form of ocean acidification, reduced oxygen and rising temperatures.

All these factors have pushed us to realise that care of our oceans cannot be considered in isolation from different human uses.

Care of our oceans cannot be considered in isolation from different human uses

Issues the health of our ocean faces are part of one global system and so the approach to solutions must be addressed in the same way. The Systems Thinking school of critical thought sees a problem as part of a much larger tapestry.

Systems thinking about impacts on natural capital, ecosystem services and the functioning of the ocean and land is important, because it then goes on to consider how impacts promulgate to affect economies and societies. We can also identify solutions that create equitable and sustainable outcomes globally from our use of the ocean and its natural resources, but also some of our activities on land.

It is critical that solutions are equitable, sustainable and owned by the community.

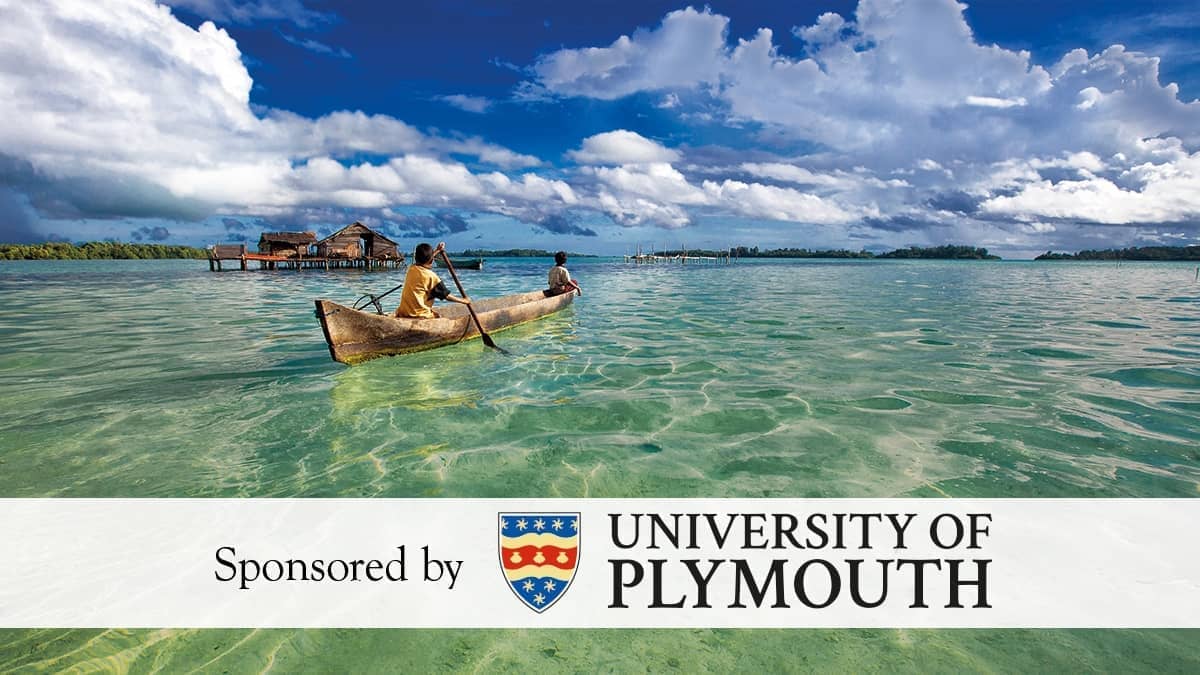

I’ve seen first-hand, through my work in South East Asia, the benefits that can be reaped by our oceans – and the communities that directly rely on them for food, income and wellbeing. There, we considered the whole system, working with local communities and researchers to co-create solutions to enable the sustainable use of marine resources that support the livelihoods of the coastal communities and protect fragile marine ecosystems.

The transformative change needed to protect our oceans inevitably relies on global leadership. Some progress was made at the UK-hosted G7 and COP26 conferences in 2021 with a real focus on addressing the critical pressure point, climate change.

What is needed next is the development of approaches and strategies that will minimise environmental damage to the seabed. For example, any policies towards producing offshore renewable energy infrastructure to maximise clean energy production must also seek to be nature positive – to restore marine biodiversity, and consider opportunities for sustainable food production from shellfish and seaweed aquaculture and even tourism – through wildlife watching and sea angling. Funding carefully designed artificial structures that address multiple needs should be a priority. This should be hand in hand with careful management towards sustainable extraction of all marine resources and increased management of marine protected areas that restores and enhances biodiversity and maintains ocean resilience in the face of rapid change.

The health of the planet will depend on the health of our oceans which is inevitably determined by decisions, actions and interactions made by people on land. One system, one future, last chance.

To read more about Mel’s research, visit www.plymouth.ac.uk/plymouth-pioneers

Mel Austen has been leading and delivering a broad spectrum of interdisciplinary research projects to support the blue economy and protect our oceans for over 20 years. She is member of the UK Government’s Natural Capital Committee and its Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC).

This article is free to read

To unlock more articles, subscribe to get 3 months of unlimited access for just $5

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in