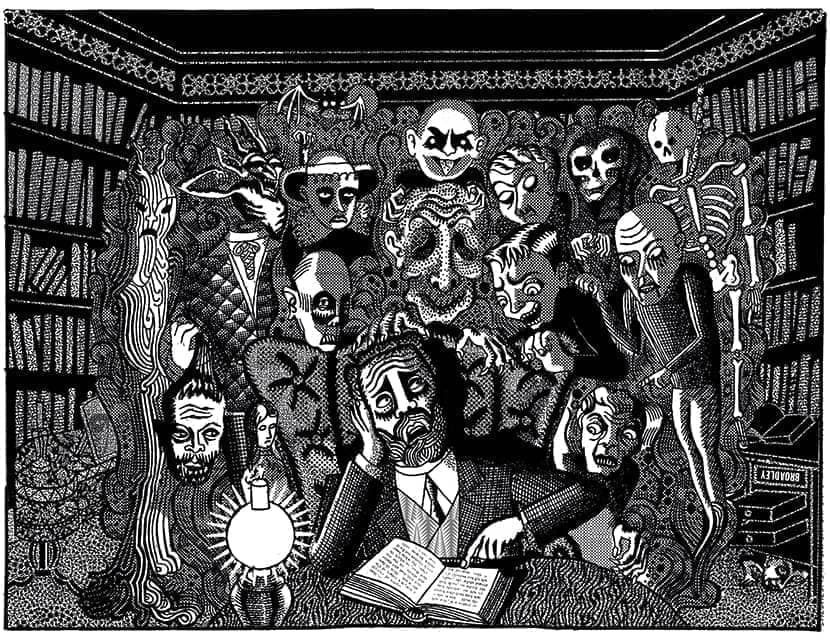

‘A sad tale’s best for winter,’ says little Mamillius in The Winter’s Tale: ‘I have one/ Of sprites and goblins…’ (He is dead by Act III.)

Ghost stories have always been best told on a midwinter night — preferably aloud, in a group drawn close together around a blazing fire.

Disagree with half of it, enjoy reading all of it

TRY A MONTH FREE

Our magazine articles are for subscribers only. Try a month of Britain’s best writing, absolutely free.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Comments

Join the debate, free for a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first month free.

UNLOCK ACCESS Try a month freeAlready a subscriber? Log in