Despite its prestige, Vienna can seem parochial. This is as true today as it was during its turn-of-the-century golden age, when it incubated a generous welfare state – that is still with us – and all those Austro-Hungarian Empire weirdos: glowering hypnotist astrologers in full metal evening dress, hysterical socialites howling at the help from threadbare chaises-longues, fiendish necromancers summoning racial purity in front of frothing cauldrons of goulash.

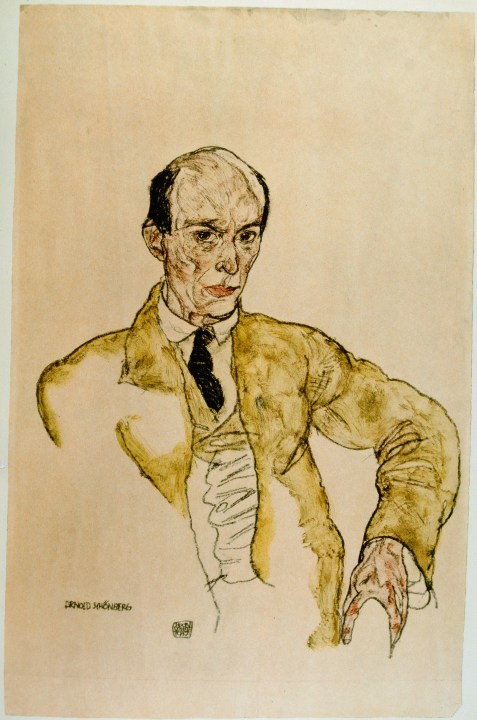

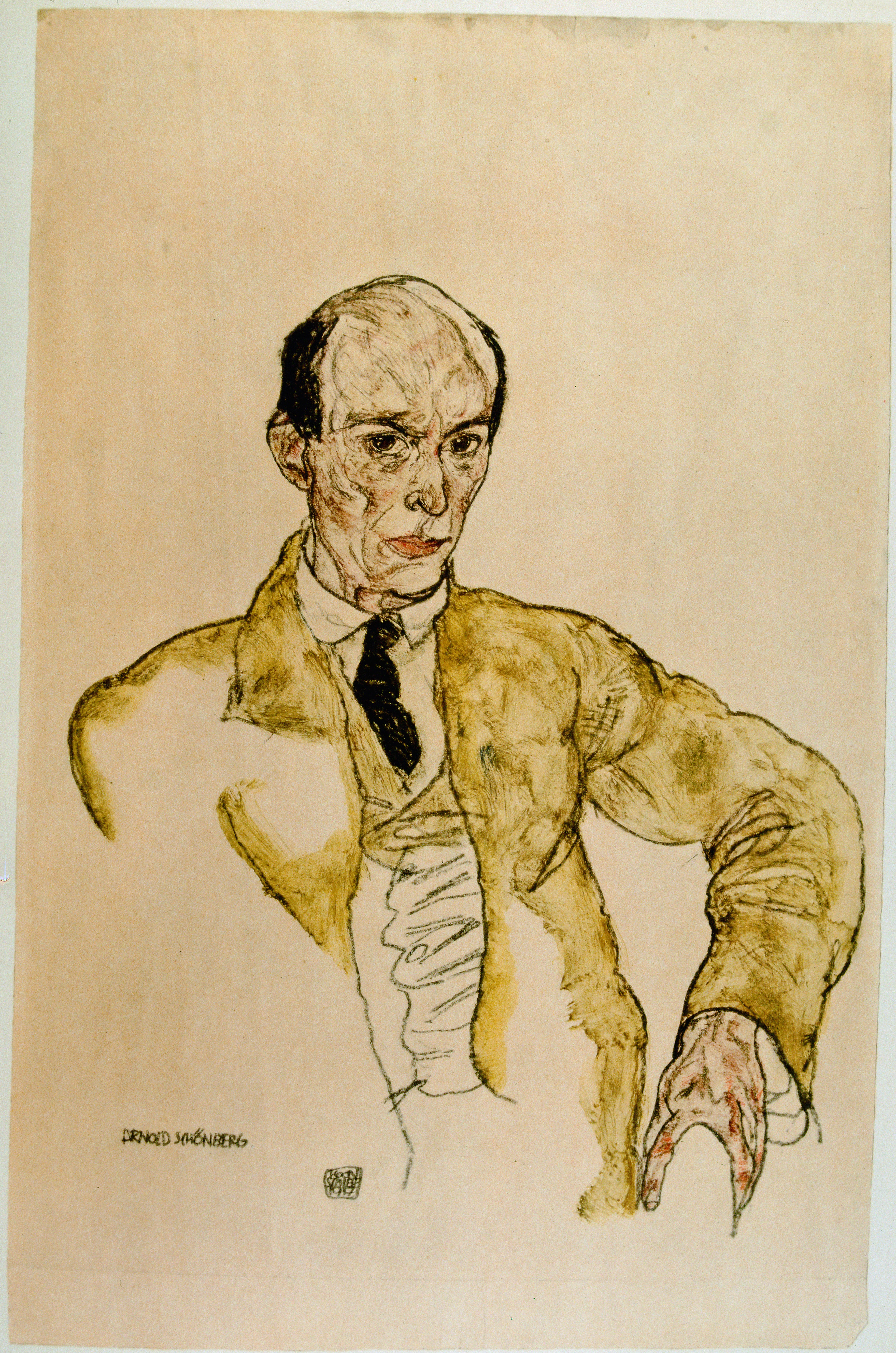

Before 1938, Vienna also had a cosmopolitan intellectual culture. Its notables, often – but not all – Jewish, included Freud and Wittgenstein, radical figures in their own fields who became well-known beyond them. Arnold Schoenberg, the ‘emancipator of dissonance’ in music, is another, but his legacy is more ambiguous. Although Vienna has been celebrating his 150th birthday all year (it was hard to miss all the posters advertising events), there’s a dissonance between who Schoenberg was, how his ideas and music were received then and since, and how the city of his birth remembers him now.

Britain’s best politics newsletters

You get two free articles each week when you sign up to The Spectator’s emails.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in