Emily Thomas is a distinguished academic philosopher who has ‘spent a lot of time by herself getting lost around the world’. Here she takes a trip to the wastes of Alaska and uses it to launch an extended meditation on a compelling question: what does it mean to travel? What is the significance of our urge to set off around the globe — not for trade, not to fight or conquer, but for its own sake?

By narrowing her remit thus, Thomas begins in 17th-century Europe, with the restless spirit of the Enlightenment. So we have no Pytheas, no Odysseus, no Marco Polo, no Ibn Battuta. Travel in her specific sense began as the prodigal child of science. It was about investigation, learning, the compulsion to explain, to understand and systemise. On completing his formal education, Descartes left home to continue it at large: ‘Resolving to seek no knowledge other than that which could be found in myself or else in the great book of the world, I spent the rest of my youth travelling.’

Travel reduces the significance of home. As you travel further, your native habitat grows smaller

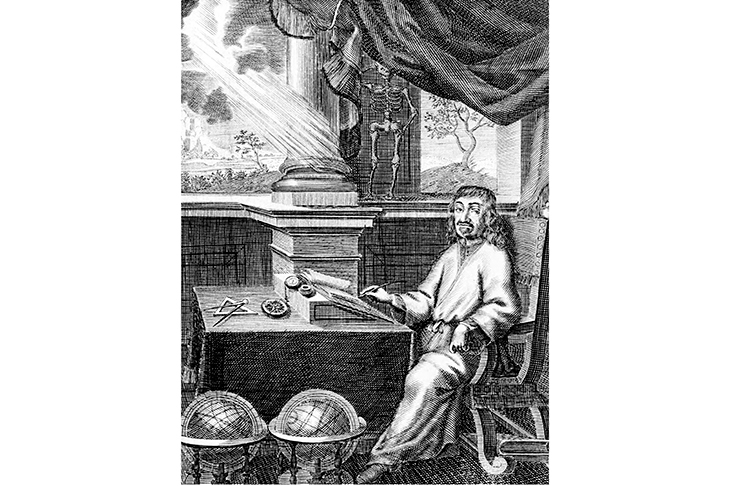

A generation earlier, Francis Bacon had already called for a complete natural history, a universal study to be conducted not by contemplation but by observation. In the frontispiece of The Great Instauration (Instauratio Magna) with its ambitious plan to restore all that there is to know, all that was lost at the Fall, a ship is set against a flat and distant horizon: ‘Many shall go to and fro, and knowledge shall increase,’ (Multi pertransibunt et augebitur scientia) reads the caption.

Travel became an empirical exercise. In London, the Royal Society met to discuss travel reports. It issued guidelines for the gathering of material (be sure to record longitude and latitude, climate, fishes and meteoric activity), and steered the itineraries of many inquisitive travellers towards places of interest — Greenland, the Caribbean, Hungary, Transylvania, Egypt and Persia. Men like Henry Blount and John Ray took to the road in pursuit of knowledge. In the 19th century, the voyages of the Challenger and the Beagle transformed our view of the natural world. Darwin quotes Bacon himself at the beginning of The Origin of Species — ‘let no man… think or maintain that a man can search too far or be too well studied’.

Yet for all its functional benefits, many of travel’s enduring rewards are more metaphysical. Thomas shows the sensibilities of travellers enlarging over the years to take in elements of the sublime, to seek out grandeur in landscape, to pursue the transcendental. Margaret Cavendish was not a traveller herself but wrote an early Utopian tract based on a fantasy journey. ‘Travellers,’ she suggests, ‘have most reason to adore and worship God best for they see most of his wonderful works.’

How do these philosophical musings inform the 21st-century traveller? Thomas gives us useful discussions of the age-old gendering of the journey, traditional male roles articulated in the roving adventurer — and how it is changing; on the increase, for instance, are scholarly studies of women travellers, which ‘chip away at the beardyness’. She speaks of trends such as ‘cabin porn’ — the online popularity of huts in the wilderness — and ‘doom tourism’ — the compulsion to see places before environmental damage destroys them.

In essence, though, the travel experience offers something perennial. It is not a pre-requisite for understanding — Socrates and Kant hardly budged at all. But for all those who do set off — be they scientist, explorer or backpacker — an immersion in the unfamiliar is invariably rewarding. Thomas distinguishes between such trips and commuting or tourism: ‘The difference between everyday journeys and travel journeys lies in how much otherness the traveller experiences.’ Otherness is the object of such travel and its own reward. ‘I want to forget my western outlook,’ mused the great 20th-century Swiss traveller Ella Maillart, ‘and feel the whole impact made on me by the newness I meet at every step.’

But going to far-off places has another effect. Travel reduces the significance of home. As you travel further, your native habitat grows smaller. The ultimate example is the 1968 Earthrise image, taken from Apollo 8: the furthest that anyone had ever travelled revealed the cosmic frailty of our planet in a picture that has been described as the ‘most influential environmental photograph ever taken’.

Emily Thomas has used her command of the philosophical canon to extend our understanding of an impulse that many of us share but few examine in such depth. The Meaning of Travel is a manifesto for the virtues that travel can bestow on the traveller — not just an increase in knowledge, but a deep humility at the scale and diversity of the world, and an enduring wonder that we live on such a planet.

Comments