It seems something of a disservice to a work of this seriousness to say how beautiful it is, but that is what will first strike the reader. Open this book and if you can prise yourself away from its wonderful marbled end papers, with their swirls and drifts of deepest blue, brilliant flashes of rusty orange, rivulets of ochre, inky spheres and floating masses of fiery red, you will find yourself taken back to the Enlightenment world of Johann Gabriel Doppelmayr’s Celestial Atlas and an age in which Europe’s polymaths were as interested in the discoveries of science as they were in the literary and artistic culture of the day.

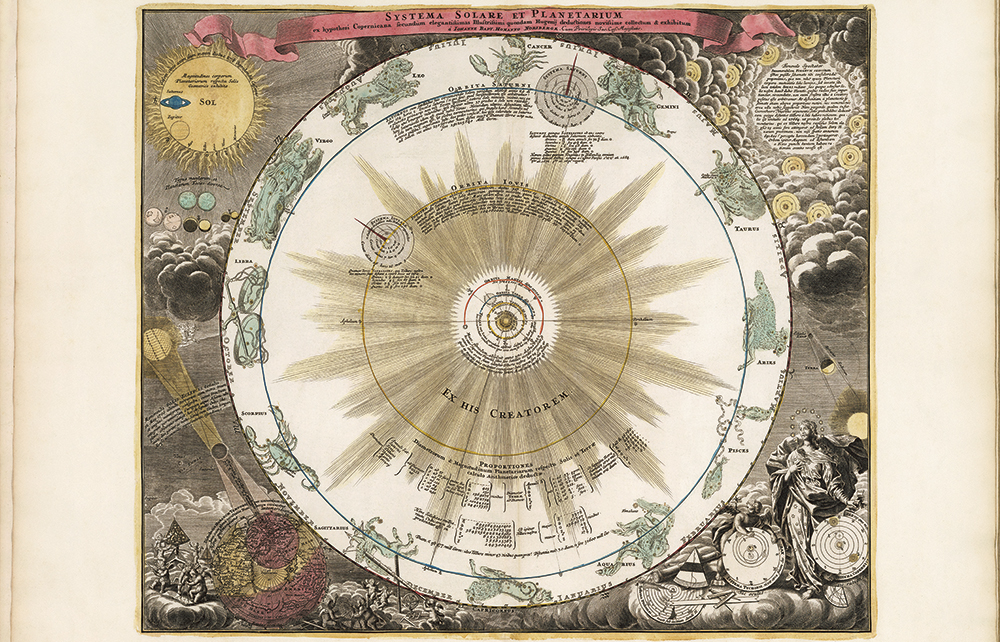

The Atlas Coelestis, published in 1742, is an extraordinary work consisting of 30 plates illustrating everything that was known of the cosmos at the time. Phaenomena reproduces these plates in double-page spreads, and then again in detail so that each part can be clearly seen. Giles Sparrow introduces and explains each plate, decoding the charts and diagrams which in the original are annotated in Latin. Interleaved with the Dopplemayr plates is a wide variety of further illustrations, making the book a comprehensive guide to the history of astronomy from Aristotle to the Hubble telescope, touching on Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Chinese, Babylonian, Islamic and many other sources en route. Its main focus, however, is the period between the revolutionary heliocentric ideas of Nicholas Copernicus early in the 16th century, gradually and reluctantly adopted by other astronomers, and the work of Doppelmayr’s contemporaries some 200 years later.

Doppelmayr came from an affluent merchant family in Nuremberg, a city that was a hub of scientific thinking, precision instrument-making and astronomy. From 1704 he was professor of mathematics in Altdorf, just outside Nuremberg, and remained there his entire life, devoting himself to the popularising of current scientific theory.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in