At a funeral in New Orleans in 1901, Joe ‘King’ Oliver played a blues-drenched dirge on the trumpet. This was the new music they would soon call jazz. A century on, from the hothouse stomps of Duke Ellington to the angular doodlings of Thelonious Monk, jazz survives in the vocal inflections of rap. To its detractors, rap presents black (increasingly, white) people to the world in terms the Ku Klux Klan might use: illiterate, gold-chain-wearing, sullen, combative buffoons. (‘Life ain’t nothing but bitches and money’, harangued the Los Angeles combo N.W.A. in a reversal of Martin Luther King’s ‘black improvement’.) Yet Bob Dylan had offered an early version of rap in ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’; rap has its pedigree.

Gil Scott-Heron, the ‘godfather of rap’, fashioned a jazz-inflected street poetry that mirrored the harshness of life in the housing projects, vacant lots and hustler turfs of black inner-city America. Born in Chicago in 1949, he spent his childhood in Jackson, West Tennessee, where segregated streetcars and unfriendly, white-owned stores were the commonplace. Raised by his grandmother Lily Scott, a laundress who ‘did’ for the local whites, young Gil grew up with a powerful sense of racial grievance. His greatest songs — ‘The Revolution Will not be Televised’, ‘Home is Where the Hatred Is’ — were influenced by Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton’s book Black Power, which called for a recuperation of ‘African consciousness’ in the mind of the modern African American (a strategy that has evolved to its unsophisticated form in today’s obsession with ‘respect’).

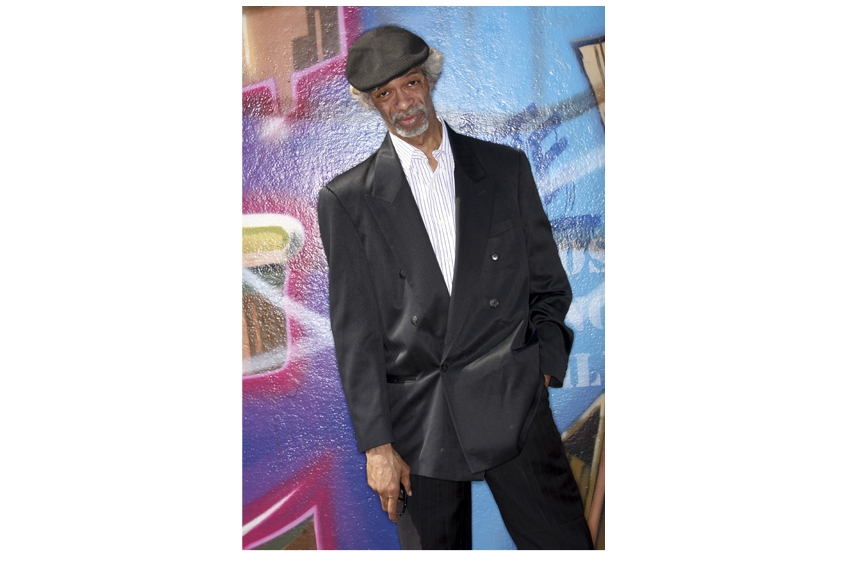

Yet, for all his righteous talk of black self-empowerment, Scott-Heron steered clear of party politics and the wilder aspects of Afro-centric militancy. His songs, with their witty verbal thrusts and parries, showed an elegant control of language and a hymnal, incantatory quality that shone bright on his magnificent last album, ‘I’m New Here’, released in 2010 a year before he died. Scott-Heron’s croaky, nicotine-thick voice and death-haunted lyrics showed that rap had not, after all, become the degraded soundtrack to Hennessy brandy adverts and Nike trainers. At the age of 60, he remained a master of the word — ‘lyrically active’, as they say in Jamaica — and church oratory-style improvisation.

His life, as he relates it in this posthumous memoir, The Last Holiday, has the savour of an old blues ballad. In 1960, following his grandmother’s death, Scott-Heron went to live in the Bronx, where jazz proved to be a revelation. Excited, he began to improvise Coltrane and Parker riffs on the school’s Steinway piano but, bizarrely, was given a lead role in the end-of-term production of The Mikado (neither Gilbert nor Sullivan had ‘a fan club in the ghetto’, Scott-Heron notes dryly). Meanwhile his father, a Jamaican-born professional sportsman, was offered a contract to play football with Celtic in Glasgow. Scotland was not so alien a destination for his father. ‘He was, after all, already a citizen of the Commonwealth.’

After attending Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, Scott-Heron hit the New York streets as a hustler and would-be author, publishing a noirish novel, The Vulture, in 1969. The novel is haunted by Martin Luther King’s assassination the previous year. Lyndon Johnson-era America, to Scott-Heron, seemed to be a murky underworld where criminals were in cahoots with politicians, and where segregationists could run for the White House on the ‘anti-nigra’ ticket. The Last Holiday offers, among other things, a James Ellroy-like cast of Ku Klux Klan mayors, redneck presidential aides and Fed-grey surveillance operatives, whose amorality contrasts with Martin Luther King’s moral sobriety.

The book’s first half, where Scott-Heron recounts his Tennessee childhood, is fascinating. Like all the best jazzmen, Gil had leaned to keep rhythm in church, and was taught to play hymns on the piano by a local Baptist. Later, Scott-Heron’s first album, Small Talk at 125th and Lenox, would hint at a melancholic, minor-key sound that mirrored the Revivalist religiosity of black America and the belief that ‘jazz is America musically’.

Parts of The Last Holiday, unfortunately, read like a preliminary sketch to be coloured in later: Scott-Heron did not live to make the textual alterations he may have wanted. Yet, for all its occasional flaws, this is a marvellous documentary of black America and life lived in the raw.

Comments