West Germany’s first chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, hated eastern Germany and said – possibly apocryphally – that Asia begins at the east bank of the Elbe River. When people visit my forest in what’s long been Brandenburg’s rustbelt, I caution that Asiatic Germany isn’t Adenauer’s bucolic Rhineland, let alone Munich or Hamburg. Yet the ‘rustbelt’ moniker no longer suits a region that, while down and out for decades, is rebounding, powered by new industry and proximity to booming Berlin, the capital’s new airport and a Tesla factory. Even low-tech forestry is making money after having been on life-support five years ago.

But there are also levels of anger I have never seen in the 22 years I’ve lived here. What riles people up? Record numbers of migrants; climate, car and farming policies tailored for urban voters that ignore rural realities; and a German economy mired in recession. Trust in chancellor Olaf Scholz’s Social Democrat-Green-Liberal coalition is plunging – and contempt and hatred are fuelling the rise of the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD).

There are also levels of anger I have never seen in the 22 years I’ve lived here

The AfD is anti-migrant, pro-Russia, pro-China, anti-US, anti-EU and anti-euro. Parts of it are deeply anti-democratic. A speech by an AfD member of Brandenburg’s state parliament vowed to ‘abolish the party state’ when it takes power.

It attracts ‘Germany for the Germans’ nationalists and thuggish, right-wing extremists. The AfD also draws conservatives made homeless by ex-chancellor Angela Merkel who moved her Christian Democrats to the left. Finally, it’s a protest party for voters who see no other way to force the stubborn Scholz to change policies.

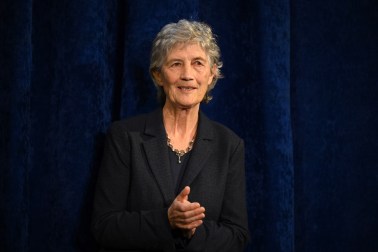

Yet the AfD is also not your grandfather’s jack-booted movement. Its co-leader, Alice Weidel, is a former Goldman Sachs banker, who speaks mandarin and is a lesbian with a Sri Lankan partner and two children.

When visitors come to the forest where I live, they often ask what it’s like to live in a region that adores the AfD. Short answer: even though I look like a bloody foreigner and speak German with an accent, I’ve never had a problem.

The village, Bärenklau, is so far east of the Elbe that it’s almost in Poland. Aside from a century-old Schloss, there’s little here. The locals are the attraction. They’re independent and self-sufficient with their own chickens and sheep. Many still heat with wood.

Anita Fiedler is a force of nature. She sits on the village council yet, in a most un-Germanic manner, bypasses formal channels to get things done using her network of friends and not always gentle arm-twisting. A political independent, Anita says almost everyone she knows plans to vote for the AfD in Brandenburg’s local elections in June. The AfD is also leading polls in the run-up to regional votes in eastern Brandenburg, Saxony and Thuringia states this September.

‘People are furious that we’re spending so much on migrants, on foreign aid and the Ukraine war,’ she says. ‘What about our own people? What about our farmers?’

Much has been made of demonstrations across Germany in past weeks aimed at the AfD. The trouble is, these have been more about virtue-signalling morally clean positions than finding ways to win back far-right voters. Organisers are leftist groups and the German national flag was nowhere to be seen at many of the protests.

‘The AfD emerges from the wave of protests unscathed,’ said a Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung commentary. This remains the case ‘as long as the (protest) movement does not consist of dealing with concrete questions that led to the rise of the AfD and the decline’ of the established parties.

The mood in this part of Brandenburg remains combustible even as the region, a 90-minute drive southeast of Berlin, stands on the cusp of economic rebirth. A nearby lignite strip mine supplied brown coal to the Jänschwalde power plant for half a century. Mining ceased on the 31 December and Jänschwalde, which will close in 2028, is one of the dirtiest power plants in Europe. Its electricity goes to Berlin where smug hipsters use it to charge their Teslas.

It’s the hipsters who may have the last laugh

However, it’s the hipsters who may have the last laugh. The region has huge solar parks, the biggest built on a former Soviet air base. The reclaimed strip mine will be covered with wind turbines. The region is getting €10 billion (£8.6 billion) to transform from brown coal to renewables.

Growth is even coming to luckless Guben, down the road from me. The world ended here in 1945 when Soviet forces bombed the city to Kingdom Come. Almost 90 per cent of the old town was destroyed and Guben never recovered. Its population was 46,000 in 1939. Today it is 16,000.

A lithium processing factory is now planned, as is a battery recycling plant. A factory making the BiFi sausage snack, sold at petrol stations across Europe, will begin production this summer. The town I assumed was dying is in resurrection. Yet politics here is a different matter: post-1989 deformations still reverberate. Guben suffers the lingering effects of what Robert Conquest called Marxism’s ‘Mindslaughter.’

There’s a failure to be clear-eyed about past communist crimes. Not a week goes by without someone telling me that life in East Germany was better because of X, Y or Z. There’s also a sense of victimhood seemingly drawing on East Germany’s claim to have been the first Nazi victim because of the Third Reich’s persecution of communists. This, along with lower party allegiance than in western Germany, makes voters open to new political movements.

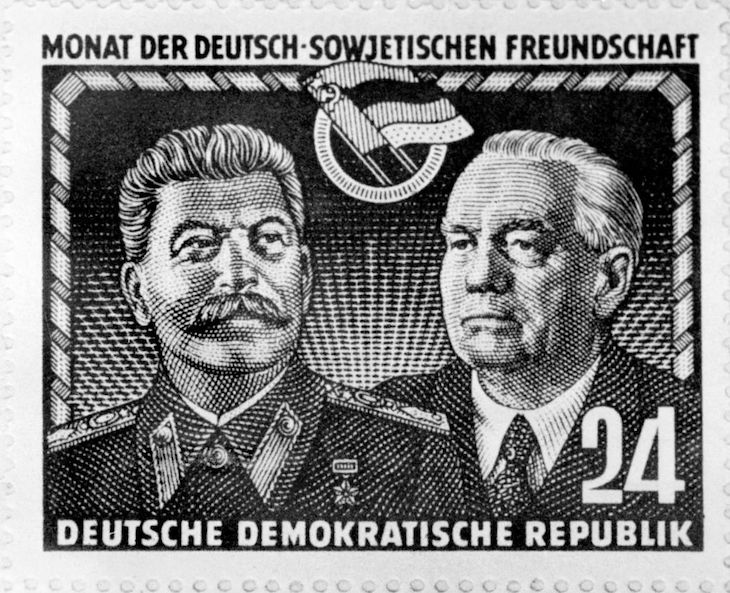

One example of lingering East Bloc blinders: Wilhelm Pieck was the first and last president of communist East Germany. Sent by Stalin in 1945 to impose Kremlin rule, Pieck still has a huge monument in Guben. Built of concrete and cast-steel images of a heroic Pieck, it’s ringed by grim, East German Plattenbauten tower blocks.

Its restoration, at a cost of over €100,000 (£85,000), was approved in 2014. Amazingly, nobody thought it necessary to include an explanation of Pieck’s real achievements: Stalinisation of his own party and his rare use of a pardon to save those condemned to death. The past was viewed as a rose-tinted mix of noble intentions of a hometown boy, gone slightly array.

Last November, city officials finally put up a small sign next to the Pieck edifice which, as they said in almost Harvard Claudine Gay-style, puts the monument ‘into context’.

Perched above Guben is another part of history that locals view, if at all, then with indifference: a walled cemetery of the vanished Jewish community. There’s a memorial to the six Guben Jews who died as soldiers in World War I. The last was Fritz Levy, killed on 14 June 1918. The most recent gravestones are from 1937.

There’s still too much casual anti-Semitism

There are no more Jews here and in regular visits to the cemetery I have never met a soul. Why does this worry me? There’s still too much casual anti-Semitism which lowers the inhibition to vote for extremist parties. Back in Bärenklau, a tree symbolises my unease over the region’s past, its economic rebirth and lurch to the far-right.

The ‘Thousand Year Oak’ – yes, it’s really still called that – is hollowed out and rotting yet produces abundant acorns. If you look up into the tree there’s a disquieting sight: a protruding dagger. Years ago, a neighbour with a penchant for Third Reich militaria, got roaring drunk. Dressed in white sheets he scaled the tree, shouting obscenities. Before police brought him down, he rammed in the dagger.

Every year, I expect the dagger to fall out of the tree. It never does. It brings to my mind Goethe’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice: ‘Die ich rief, die Geister / Werd’ ich nun nicht los.’ – ‘The spirits that I summoned / I now cannot rid myself of again.’

The leaden melancholy of Adenauer’s gateway to Asia takes getting used to. I’ve been here one-third of my life and once you summon up the spirits, they never leave you.

That melancholy is shedding as the rustbelt revives. Yet the AfD political spirits – bubbling up in a region that was Nazi or communist for 57 of the past 79 years – are strengthening faster than the economy.

For the first time since the 1990 German reunification, the former communist east may be proving a political bellwether for the nation.

Comments