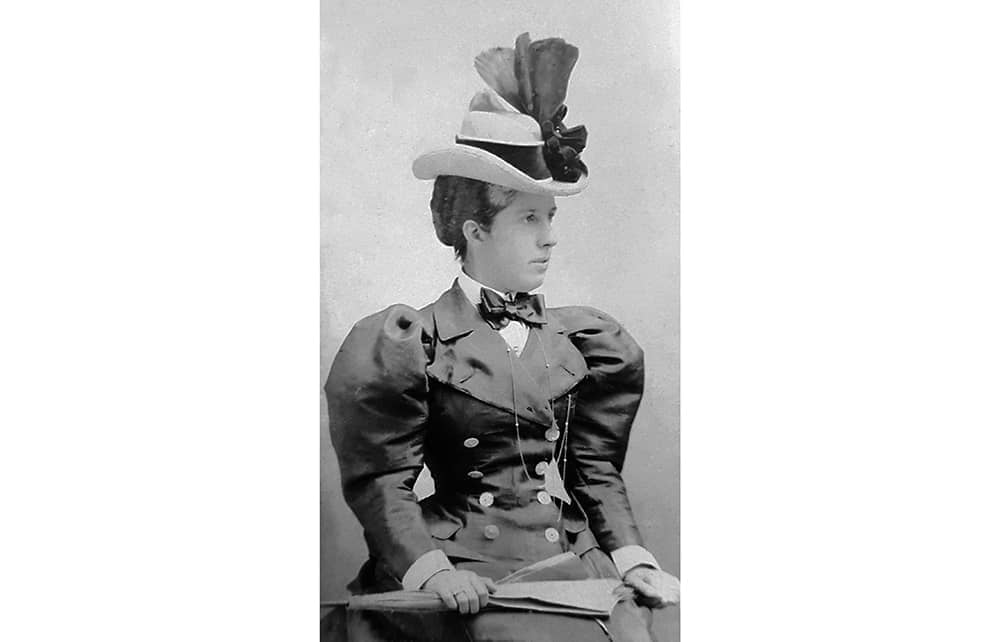

In October 1897, the grandees of the Royal Horticultural Society gathered to bestow their highest award, the Victoria Medal of Honour, struck to commemorate the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee, to 60 of gardening’s greatest luminaries. For the first time, these included two women. One was Gertrude Jekyll, known by all as the Queen of Spades; the other was the 39-year-old Ellen Willmott.

But Willmott did not turn up. This public snub was the beginning of her reputation as ‘gardening’s bad girl’, as Sandra Lawrence puts it, one that increased exponentially until it exploded in stories of daffodils being booby-trapped to deter bulb thieves. By trawling through innumerable newly discovered diaries and documents, Lawrence believes she has found the reason both for Ellen’s no-show and her seeming change of personality. Thus her book, packed with detail, is one where the author’s search for information is part of the story.

It had all begun so differently. The young Ellen was popular, intelligent and lighthearted. She had a happy childhood in an affluent family of the rising Victorian middle class; from the age of seven she would come downstairs on her birthday morning to find on her plate a cheque for £1,000 (today worth £126,588) from her immensely rich godmother. Unsurprisingly, she never learned the value of money and thereafter simply bought what she wanted.

In 1876 Ellen’s father Fred acquired Warley Place, an estate 18 miles from London that consisted of a Queen Anne house, its cottages and 33 acres of land – later, much more would be added. The whole family was gardening- and dog-crazy, with seven poodles, a Newfoundland, a Pomeranian, a St Bernard and innumerable collies, corgis, sheepdogs, dachshunds and terriers. There were balls, parties, visits to London for Ellen and her younger sister Rose to take German lessons, expeditions and travel: the family went to Antwerp, Paris, Nice, Monte Carlo and, especially, the Alps, where Fred’s gout and his wife’s rheumatism seemed to improve.

Ellen kept a revolver in her pocket, and reputedly booby-trapped daffodils with explosives to deter bulb thieves

Alpine gardens, which became known as rockeries, had begun to be hugely fashionable.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in