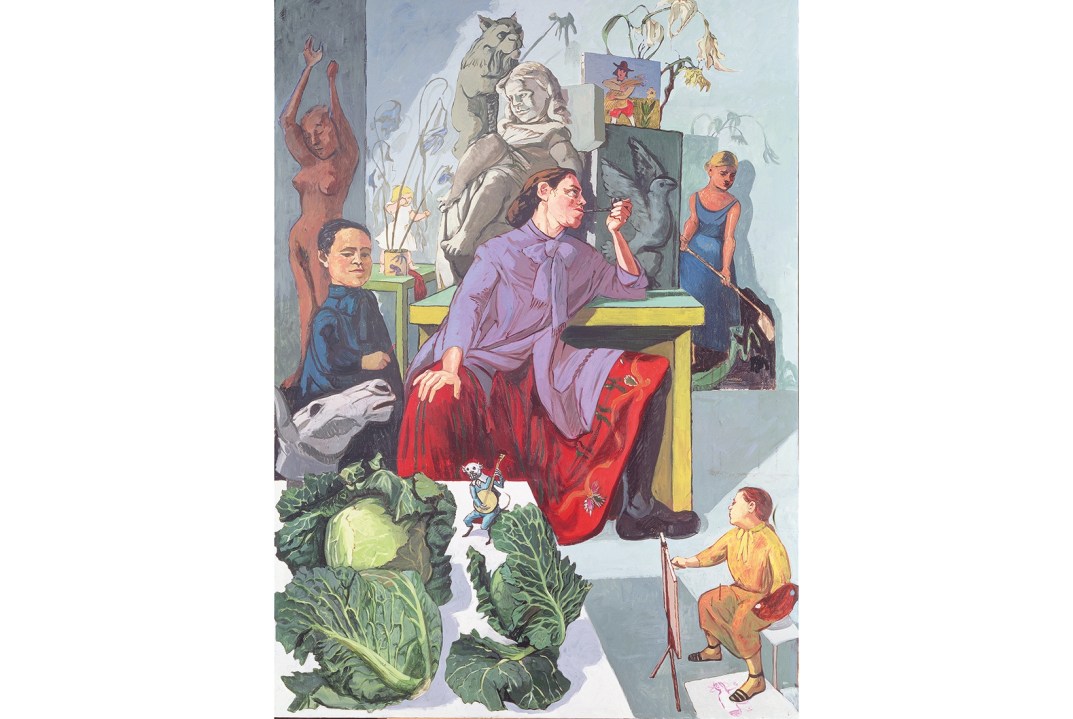

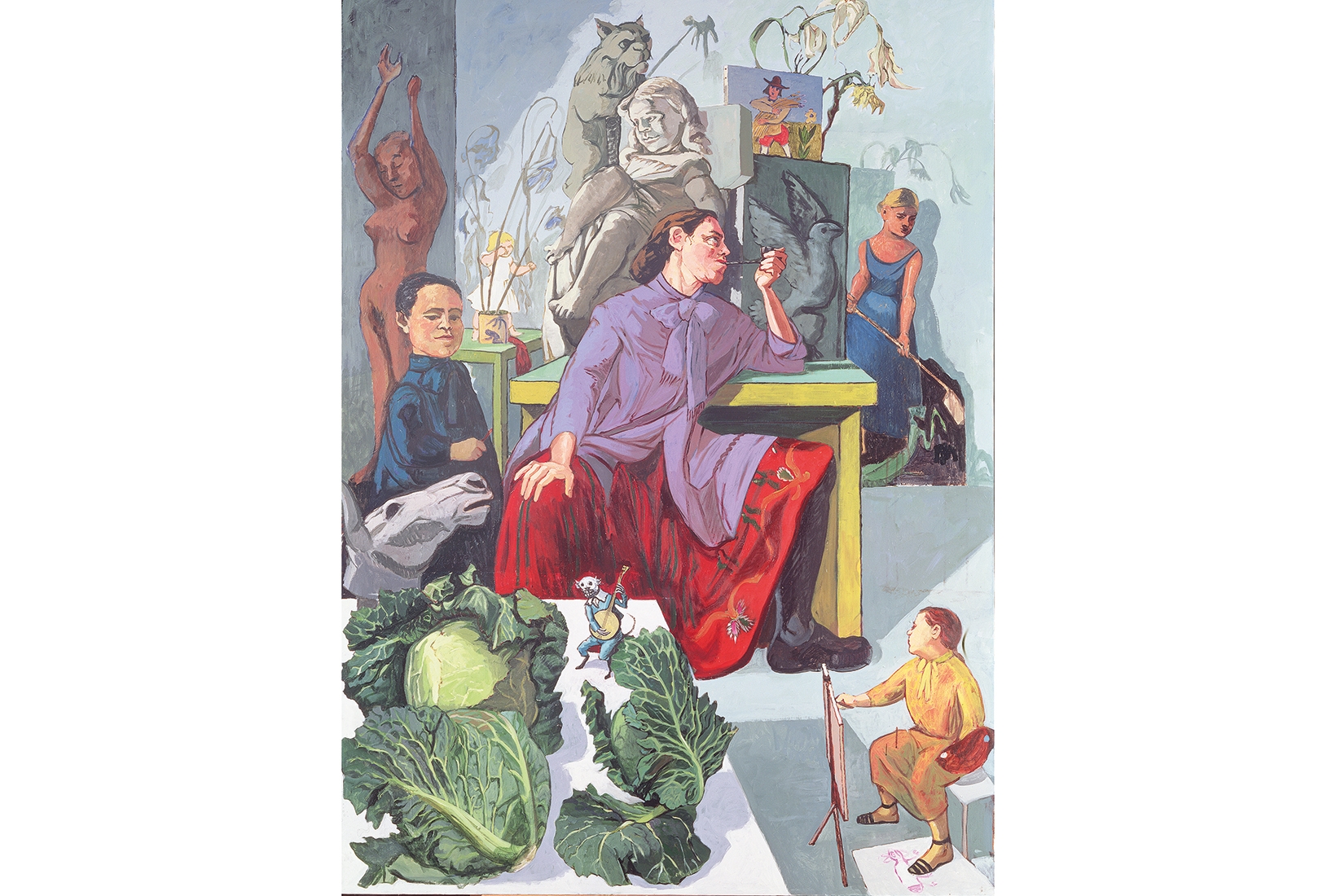

The Victorian dictum ‘every picture tells a story’ is true of Paula Rego’s works, but it’s only part of the truth. Rego has said that she hopes and expects that when people look at her pictures, ‘Things will come out that I’m not even aware of.’ And that’s right too: every marvellous picture tells so many stories, and is so charged with under- and overtones, that no one, including its creator, can be aware of everything that’s going on.

That’s certainly true of many works in the Rego retrospective at Tate Britain. All notable painters and sculptors are, of course, sui generis. They don’t follow established rules; instead they make up a new set to suit their own creative personalities. So the show, as well as revealing Rego’s greatness (at least to those who were not conscious of it already), also poses a question: what kind of artist is she?

Both biographically and aesthetically, Rego is a hybrid. Born and brought up in Portugal, she went to art school in London, and has spent most of her long life (she was born in 1935) in Britain. I once asked her whether she felt more Portuguese or British. She replied: ‘I’m really both, exactly both.’

Her little-known early works are the major revelation: full of quivering innards and an atmosphere of menace

What’s more, she’s worked against the grain of both cultures. Rego arrived in this country in 1951 and studied art at the Slade, which was then dominated by the doctrines of austerely truthful naturalism instilled by the principal, William Coldstream.

Up to a point, she accepted Coldstream’s advice always to paint what she knew and cared for. Thus in 1954, tackling the set subject for a student composition — Dylan Thomas’s ‘Under Milk Wood’ — she turned to a Portuguese kitchen.

Comments

Join the debate for just $5 for 3 months

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for $5.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just $5 for 3 monthsAlready a subscriber? Log in