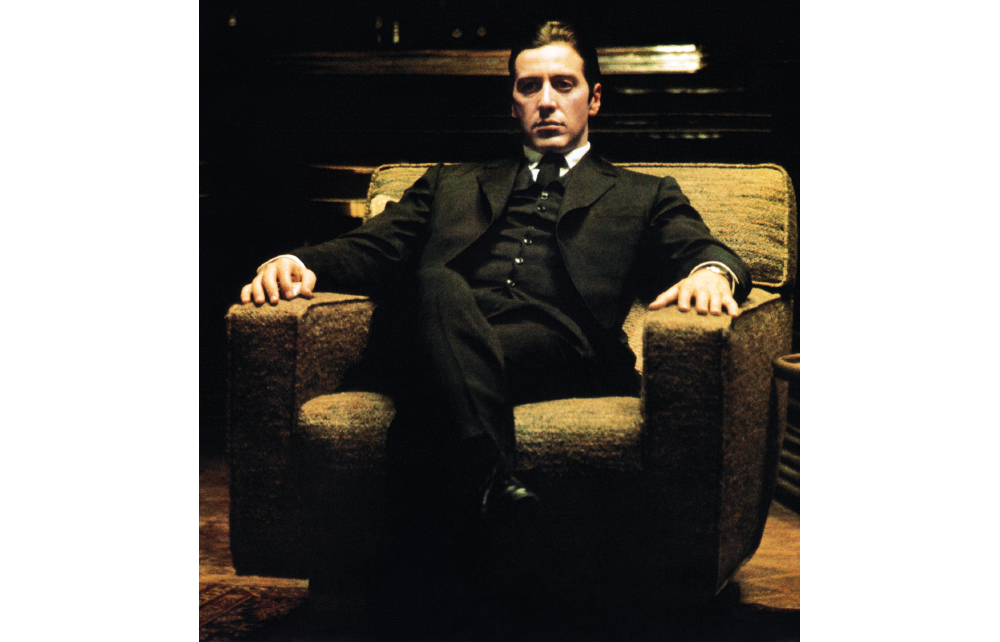

Ellen Barkin, Al Pacino’s lover-cum-prime- suspect in his comeback movie Sea of Love (1989), once dismissed the artifice of the British acting tradition (by way of an oddly ill-tempered pop at Nigel Havers) by comparing it with the immersive naturalism of the greats of post-war American cinema: Marlon Brando, Meryl Streep, Robert De Niro and Al Pacino.

Disagree with half of it, enjoy reading all of it

TRY A MONTH FREE

Our magazine articles are for subscribers only. Try a month of Britain’s best writing, absolutely free.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Comments

Join the debate, free for a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first month free.

UNLOCK ACCESS Try a month freeAlready a subscriber? Log in