An ocean of clichés surrounds Britain’s maritime history, from Chaucer’s Shipman to the ‘little ships’ at Dunkirk. Tom Nancollas, whose 2019 Seashaken Houses treated lambently of lighthouses, now navigates debris-strewn territorial waters, sounding their depths.

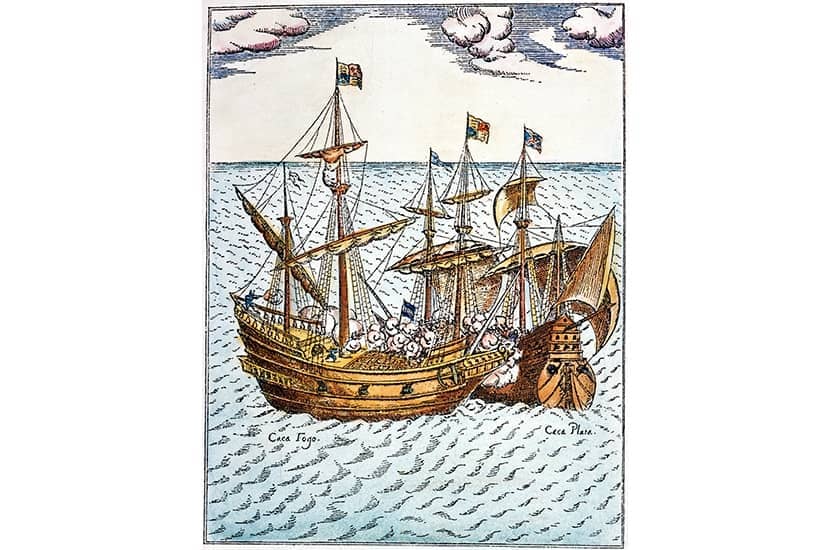

He examines 11 craft, from Bronze Age boats to ironclads, that epitomise Britain’s complex compact with the sea. Ships, so sturdily island nation-shaping, are themselves evanescent, exposed to danger and decay, and discarded once defunct. But their traces can be found almost anywhere. Even those that are now only names (the Conqueror’s flagship Mora, Cabot’s Matthew or Grenville’s Revenge) are ‘ensouled’ to this author – ‘lost characters of British history’, as worthy of salvage as the Mary Rose.

The sunken cargoes he seeks are not necessarily treasure. He emphasises the uses of British ships in oppressions, from imperial conquests to slavery. Lloyds’ Lutine Bell, rung to warn that a vessel was missing, should sound out now, he says, to signify national complicity in old cruelties.

He begins in Dover, England’s entrepôt from prehistory to today’s immigrant dinghies, with a 3,500-year-old prow, found in 1992, from one of the earliest vessels known in northern Europe.

Get Britain's best politics newsletters

Register to get The Spectator's insight and opinion straight to your inbox. You can then read two free articles each week.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Comments

Join the debate for just $5 for 3 months

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for $5.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just $5 for 3 monthsAlready a subscriber? Log in