The train from Zurich to Lucerne tips you out right by the lakeside, practically on the steamboat piers. A white paddle-steamer takes you out of the city, past leafy slopes and expensive-looking mansions. Tribschen, where Wagner wrote the ‘Siegfried Idyll’, slides away to the right as you head out across the main arm of the lake. At the foot of Mount Rigi, shortly before the steamer makes its whistle-stop at the lakeside village of Hertenstein, is a promontory where – if the sun is coming from the west – a yellow-coloured cube shines among the trees. This is the house that Sergei Rachmaninoff built between 1931 and 1934: Villa Senar, his last attempt to make a home outside Russia in Europe.

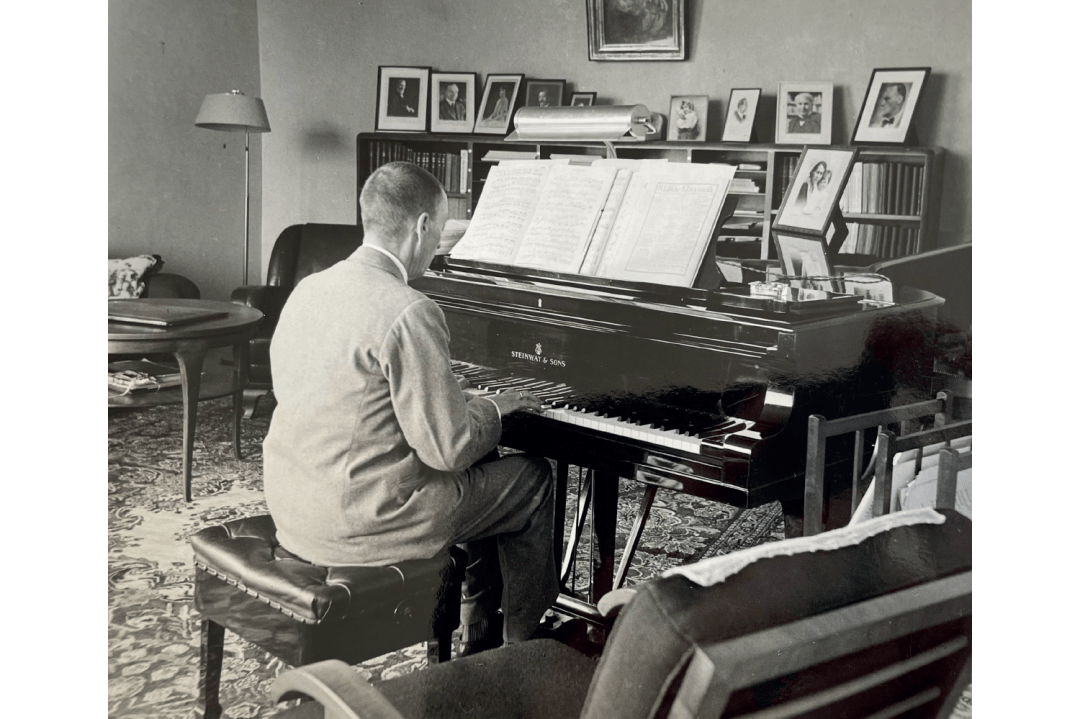

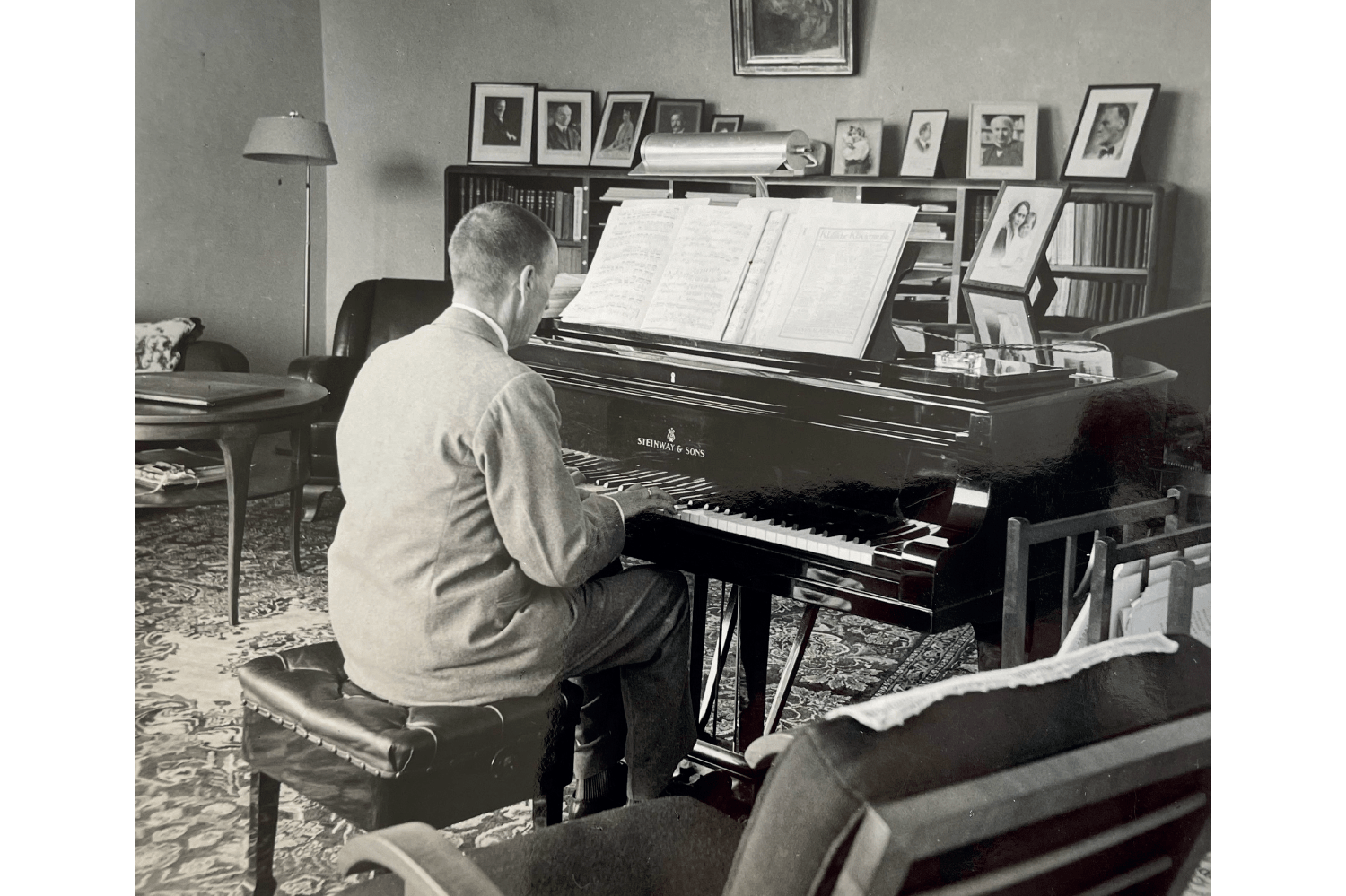

After concerts in Paris he would oust his chauffeur and set speed records back to Lucerne

It isn’t what you expect; at least, not if your idea of Rachmaninoff is shaped by the lushness of his music. You approach Villa Senar (the name comes from the first two letters of his and his wife Natalia’s names and the r of Rachmaninoff) along a curving driveway through a miniature arboretum. Every tree was chosen and placed by the composer; a lilac hangs over the path and if you know Rachmaninoff’s songs, that’ll prompt a smile of recognition. But the house at the end of this romantic vista is starkly modernist: a low, flat-roofed assemblage of right angles and plate glass whose ochre walls can’t disguise the influence of Adolf Loos and Le Corbusier. In fact, it was designed by local architects, but the specification was Rachmaninoff’s, right down to the sole ornament – the initials SR in slim deco lettering on the front door. Other Tsarist emigrés recreated little Petersburgs of velvet plush and bubbling samovars. Rachmaninoff – a man routinely described as ‘a ghost’ in his own lifetime – built himself a sleek new machine for living.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in