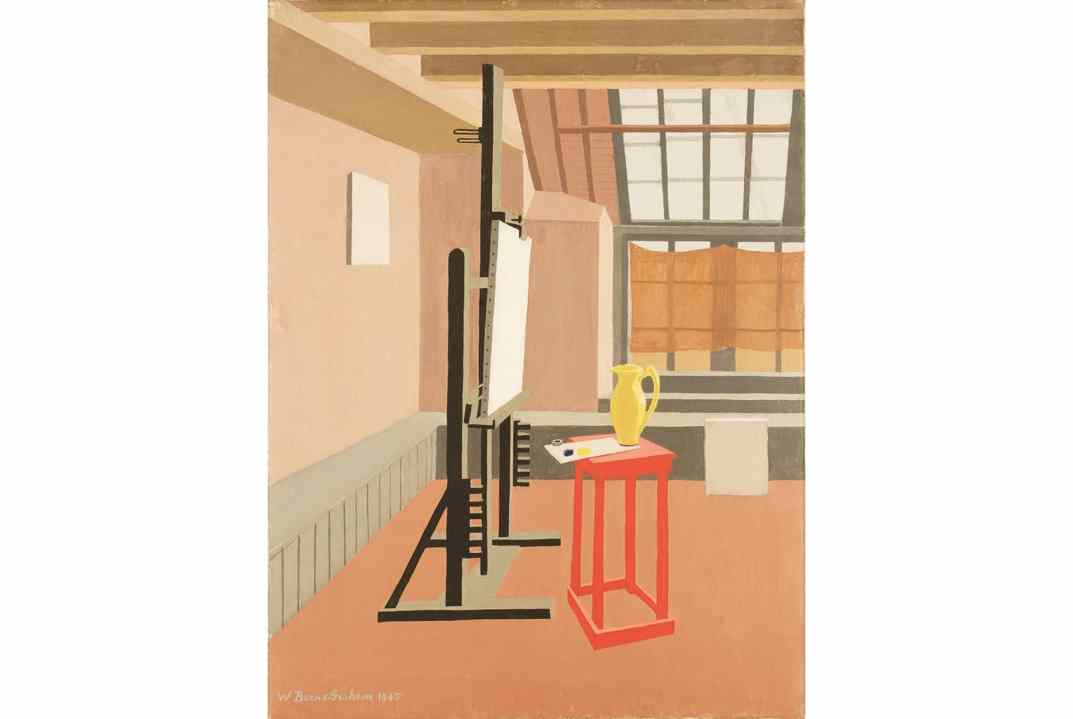

Picture the artist’s studio: if what comes to mind is the romantic image of a male painter at his easel in a grand interior with an admiring audience and a nude model at his elbow, you’re in the wrong century for the Whitechapel Gallery. Its new exhibition, A Century of the Artist’s Studio, runs from 1920 to 2020, and there’s precious little romance about it.

To be honest, the studio was never that romantic; Gustave Courbet’s ‘The Artist’s Studio’ (1855), the main source of the stereotype, was itself a send-up. The Whitechapel’s show sets out to complete Courbet’s work, dismantling the myth cliché by cliché. ‘The artist hero… is both abject and absurd,’ Dawn Adès writes in the catalogue. ‘Is the painter a shaman, a sacrificial victim or the sexualised infant that we repress in ourselves?’ All options are on the studio table in this show.

The Whitechapel’s show sets out to dismantle the myth of the artist’s studio cliché by cliché

In the opening display of photographs of famous male artists in their studios – Matisse, Giacometti, Brancusi and the octogenarian Picasso, posing for Robert Doisneau in his Mougins workshop in 1963 draped in an orange beach towel like a Roman toga – the artist hero remains very much alive. But the exhibition, originally conceived as a photographic survey of artists at work, changed course after the death of Adès’s co-curator Giles Waterfield, expanding its horizons to take in a global diversity of artistic practices – solitary, collective, installationist, performative.

In its present form it’s a trip around the world in 80-plus studios, and the effect is dizzying. Flitting between the Papunya Tula Aboriginal artists’ cooperative of Australia’s Northern Territory, the Laboratoire Agit’Art of 1970s Senegal, the women’s arpilleras shanty workshops of Pinochet’s Chile and Canadian folk artist Maud Lewis’s Painted House in the wilderness of Nova Scotia gave me jet lag.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in