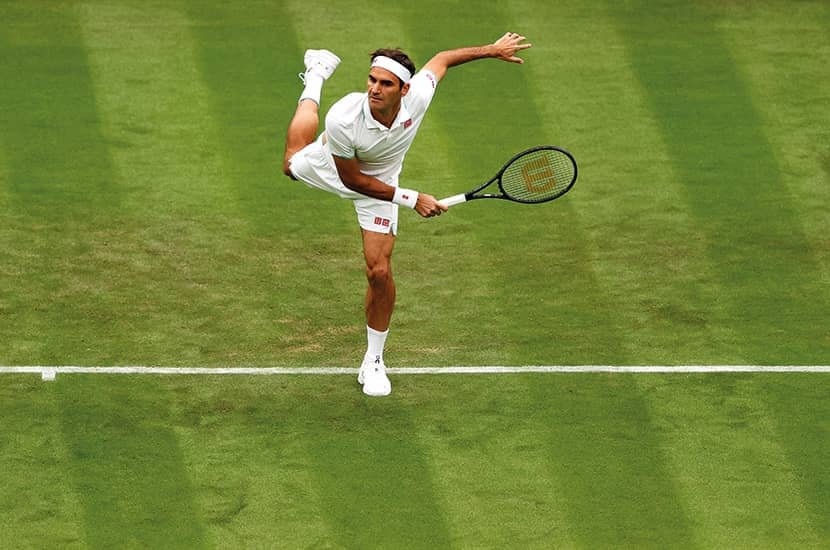

Louis MacNeice once wrote that if you want to know what chasing the Grail is like, ask Lancelot not Galahad. Because failure helps you see — the successful types are too busy succeeding. Two recent books on tennis put this theory to the test. The Master, by Christopher Clarey, long-time tennis correspondent for the NY Times, is about Roger Federer’s greatness. Clarey played for Williams College, where he ‘struggled and choked enough to understand just how difficult it can be to hit the shots that virtuosos like Federer make look routine’. Billie Jean King’s most recent autobiography, All In, is the second. She tells the story from Galahad’s point of view.

King’s is harder to sum up: part coming-out memoir, part tennis journal and part polemic. The genres overlap, of course, and some of the famous moments of her life, such as her 1973 match against Bobby Riggs (nicknamed the Battle of the Sexes), include all three. One of the odd facts about fame is that it turns even private truths into public ones, and much of the prose of All In has a certain shine on it, even in King’s confessional modes: ‘I can’t remember a time when I didn’t have a restlessness, an ambition and an urgency,’ she begins. ‘But let me tell you how I truly became free.’

Raised by working-class parents (her father was a firefighter), she discovered tennis on the public courts of Long Beach, California. Later, she turned her athletic success into political leverage. When she started on the tennis circuit, the best players, both men and women, had to pretend to be amateurs; they took kick-backs from tournament sponsors under the table. Shamateurism, it was called. Eventually, some of the players rebelled; the men formed their own professional circuit and left the women behind, even though King lobbied repeatedly to be part of the process.

A relationship with a Beverly Hills hairdresser eventually exposed Billie Jean King to blackmail

The details of all this are complicated, and involve many acronyms and breakaway leagues that fold into each other.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in