The conventional wisdom that we live in echo chambers always seemed too convenient an explanation of political polarisation to be true. Believers could convince themselves that their causes lost, not because they were faulty or fantastical or outright wicked, but because their opponents had brainwashed a majority of the electorate to reject them.

For all the credence given to it, echo-chamber theory is little more than an update of Noam Chomsky’s ‘propaganda model’ in which the media allegedly manipulates the populace into agreeing with agendas that are against its interest. This is the perfect excuse for failure: Scooby-Doo sociology that allows the defeated to cry, ‘and I would have gotten away with it if wasn’t for you meddling brainwashers.’

Certainly, on Facebook you can confine your friendships to the like-minded, if you wish. But it is technological determinism of the most vulgar kind to assume that the economic crisis of the early 21st century and the pressures of mass migration could not have transformed politics without the assistance of the web. It turns out, that even if you stick within the bounds of technology, the view that insular voters are brainwashed by the parochialism of their concerns does not stand up.

A paper published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America tested the assumption that modern men and women think the way they do because they are not exposed to information that contradicts their prejudices. The researchers paid Republicans and Democrats to follow politicians and pundits on social media with opposing political views. These were popular and authoritative figures: the best of left and right-wing Twitter could offer. As the experiment went on, the researchers monitored opinions on inflammatory issues like immigration, government waste, corporate profits and LGBTQ rights.

The results of the month-long exposure to voices you would expect to convince sceptics was that they did not convince anyone. ‘We find that Republicans who followed a liberal Twitter bot became substantially more conservative,’ the researchers concluded. ‘Democrats exhibited slight increases in liberal attitudes after following a conservative Twitter bot.’

As Christopher Bail, one of the study’s authors and the head of Duke University’s polarisation lab, told Ezra Klein of Vox, ‘For a long time, people have been assuming that exposing people to opposing views creates the opportunity for moderation. If I could humbly claim to figure out one thing, it’s that that’s not a simple process. If Twitter tweaks its algorithms to put one Republican for every nine Democrats in your Twitter feed, that won’t increase moderation.’

The researchers were at pains to emphasise that there is a vast literature which suggests that meeting opponents reduces enmity and increases the likelihood of compromise. But on social media, where so much of politics has moved, familiarity breeds contempt. The ‘backfire effect’ as psychologists call it, explodes, and knowledge of an opponent’s views reinforces rather than challenges stereotypes.

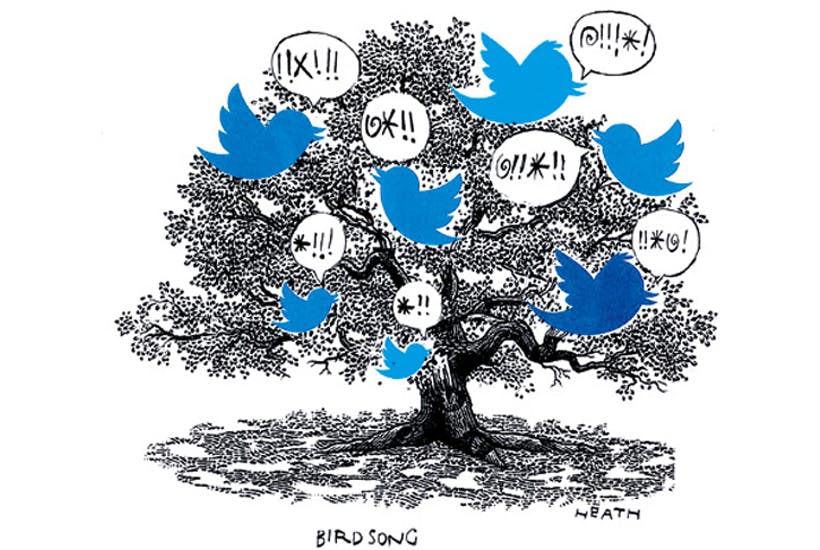

I don’t want to replace technological determinism with psychological determinism. The researchers’ conclusion feels right, however. Left and right wing Twitter pundits do not only talk to themselves. They and their followers read their enemies’ output obsessively, searching for a passage that can be taken or twisted to prove that Tories are racist or the liberal elite hates the white working class. The web has allowed the creation of sub-cultures in ‘journalism’ and comedy whose sole source of material is the real and imagined horrors of their and their audiences’ rivals. This may be tedious, but it is to be expected. Until the 1990s, leftists who wanted information on the ghastliness of the right (and vice versa) would have had to leave home and spend money on conservative newspapers. If they found the killer evidence of right-wing beastliness, they could not assume that their target audience had seen it too. Now there is the mass communication of outrage, the visceral is viral, and everyone can share their disgust.

Neither left nor right has won a decisive victory in Britain since the 2005 general election – and even then the Labour majority of 66 seats on 35 per cent of the vote was a reflection of the biases of the first-past-the-post system rather than popular support for Tony Blair.

The Duke University research suggests that partisans of both left and right should think about how their behaviour looks to those they need to convert if they want to break the stalemate. Does the post-modern left need to drive everyone who isn’t wide a-woke rightwards by fighting every culture war battle as if it were a struggle for its very survival? Isn’t it more important to defeat Donald Trump and the Tory right by finding strategies to peel off soft conservatives whose doubts might be exploited? Does the British right, meanwhile, need to alienate millions of natural Tories by tying itself to a lying lout in the US or following a Maoist Brexit, that treats compromise as counter-revolutionary deviation?

A second conclusion follows. Left and right are at their most self-satisfied when they consider why millions cannot bear the thought of voting for them. If they don’t follow Noam Chomsky, and conclude the poor dupes have been brainwashed by the liberal media/Tory press, they attribute ulterior motives. Liberals are liberal, conservatives conclude, because they want to be trendy or advance their careers in the universities and public sector. And that is true in some cases. Conservatives are conservative because they have sold out or because they are driven by bigotry. And once again there is truth in that, but it is hardly a comprehensive explanation.

The Duke University research deserves a wider audience because, when presented with the most popular and supposedly persuasive commentators on Twitter, pundits and politicians who command armies of followers, liberals concluded that the reason they can’t stand the right was the right, and conservatives decided that the very sight of the left was enough to repel them. The future belongs to the first side that understands why it is hated and tries to do something about it

Comments