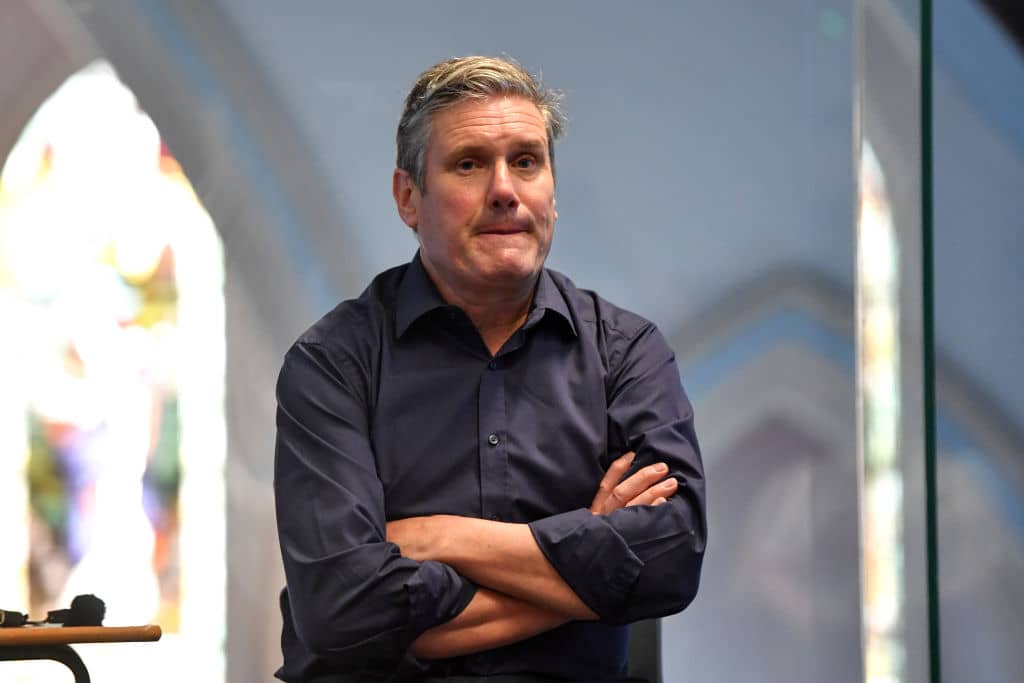

Keir Starmer’s long-awaited and lengthy essay on what he thinks the Labour party should be doing and saying has finally landed. It’s part of the Labour leader’s attempt to define himself this conference season, and sits alongside the noisy fight he’s picked with the left of the party and some of the trade unions over voting reform in leadership contests and policymaking. It’s just under 12,000 words, so it’s not an election pledge card or really aimed at voters at all. Perhaps that’s why it is largely painted in watercolour, rather than the primary colours Starmer will need to get the attention of the electorate.

But that’s not to say that this essay, which allies say represents the ‘intellectual underpinning’ of what he’ll say in his conference speech, isn’t worth reading. For one thing, it is beautifully written and has some acute observations about the state of Britain, including this lovely section about the difference between nationalism and patriotism:

‘Nationalists like to portray themselves as patriots. But patriotism and nationalism are to the same. In fact, they are opposites. Nationalism represents an attempt to divide people from one another; patriotism is about finding common ground. Nationalism is about the casting out of the other; patriotism is about finding common ground. Nationalism is the flag as a threat. Patriotism is the flag as a celebration.’

Starmer sets out ‘ten simple key principles to form a new agreement between Labour and the British people’. They are:

– We will always put hardworking families and their priorities first

– If you work hard and play by the rules, you should be rewarded fairly.

– People and businesses are expected to contribute to society, as well as receive.

– Your chances in life should not be defined by the circumstances of your birth – hard work and how you contribute should matter.

– Families, communities and the things that bring us together must once again be put above individualism.

– The economy should work for citizens and communities. It is not good enough to just surrender to market forces.

– The role of government is to be a partner to private enterprise, not stifle it.

– The government should treat taxpayer money as if it were its own. The current levels of waste are unacceptable.

– The government must play its role in restoring honesty, decency and transparency in public life.

– We are proudly patriotic but we reject the divisiveness of nationalism.

Some of these statements seem rather pointless, unless Starmer thinks that his party will have an allergic reaction to the idea that it should put ‘hardworking families first’. But they seem to form the basis of a shift to the contributory principle that Labour has been toying with for a while. Ed Miliband often picked this idea up and perhaps it is no surprise that it is fleshed out in this essay, given he is someone Starmer’s camp regard as a ‘key thinker’.

Other lines are obviously more challenging, particularly the idea that government should partner private enterprise rather than stifle it. His attitude towards the public sector seems to be that it’s time to buck up its ideas and modernise, writing that the party needs to rethink how the country works:

‘It means banishing the culture that unthinkingly accepts public services not keeping up with the sort of advances we have come to expect in the private sector. We will no longer allow corruption, waste, anachronism and falling standards to be met with a shrug, as it there is something inevitable about each of them.’

Even the sainted NHS, which Starmer of course pays full tribute to, doesn’t escape his plan for efficiencies and modernisation. He says the staffing crisis needs to be fixed in the health service but also argues, more controversially, that ‘if we can make our shopping cheaper and more convenient through the power of modern technology, then it stands to reason we can revolutionise our health and our health services.’

Elsewhere in the essay, the leader complains that business has been ‘let down by a Tory government that has failed to plan for the long term and provide the conditions in which long-term decisions can be made.’ He doesn’t mention privatisation, nationalising or public ownership. This will upset some Labour members for whom these issues remain totemic, but then again he barely talks about party members, only reminding them that their membership card reads ‘by the strength of our common endeavour we achieve more than we do alone.’ He observes that Labour has ‘at times felt like separate families living under the same roof’, particularly when it comes to debating the legacy of the 1997 Labour government. If there’s a side to pick in this, Starmer has come down firmly as a supporter of that government, pointedly praising the progress it made in a number of areas.

The essay does contain policies, but only ones that have already been announced. Presumably Starmer is saving the retail offers for his conference speech, while this piece of work explains why he’ll be picking the announcements he has. There is a lot missing beyond headline-grabbing promises, though. He is very domestic in his focus, only referring in passing to Britain’s place in the world and only then largely to complain about the way the current government has overseen messes such as our withdrawal from Afghanistan. The biggest thing that Starmer is unable to explain in this essay is whether he has the guts and the ability to push through what could, if he really believes in what he has written, be a challenging new direction for a party that has spent a decade yearning for a lurch left and away from the electorate. That’s what he has to spell out at conference, otherwise he will have wasted a great deal of ink and thinking time on an essay he will never have a chance to put into practice.

Comments