The catalogue to Making Modernism opens with an acknowledgment from the Royal Academy’s first female president, Rebecca Salter, that in the past it has overlooked women artists. To compensate, it has bundled seven – four headliners and three of their lesser-known contemporaries – into this one show.

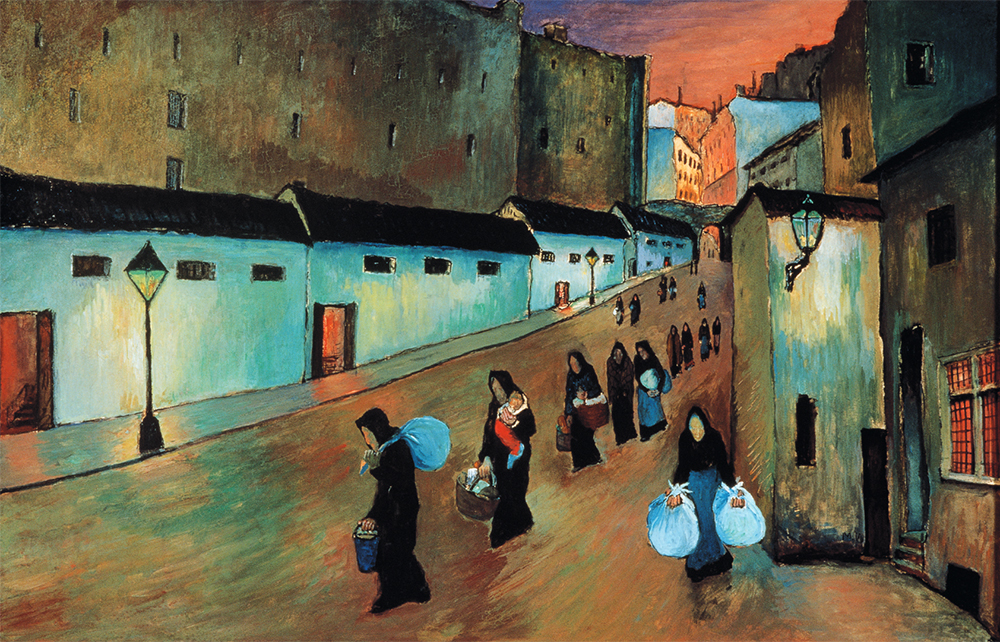

Excluded from official art schools and reliant on private tuition and ‘ladies’ academies’, these seven women escaped the feminine curse of the three ‘Ks’ – Kinder, Küche, Kirche (children, kitchen and church) – to forge independent careers in Germany before the first world war. They didn’t constitute an art movement, though Gabriele Münter and Marianne Werefkin – both comfortably off – facilitated one. Every avant-garde movement needs a base, preferably with hospitality provided, and German expressionism was generously supplied with two in Werefkin’s ‘pink salon’ in Munich and Münter’s Bavarian holiday home in Murnau. It was in Murnau, where Münter and Wassily Kandinsky spent pre-war summers with Werefkin and Alexei Jawlensky in what became known as ‘the Russians’ House’, that the seeds of The Blue Rider were sown.

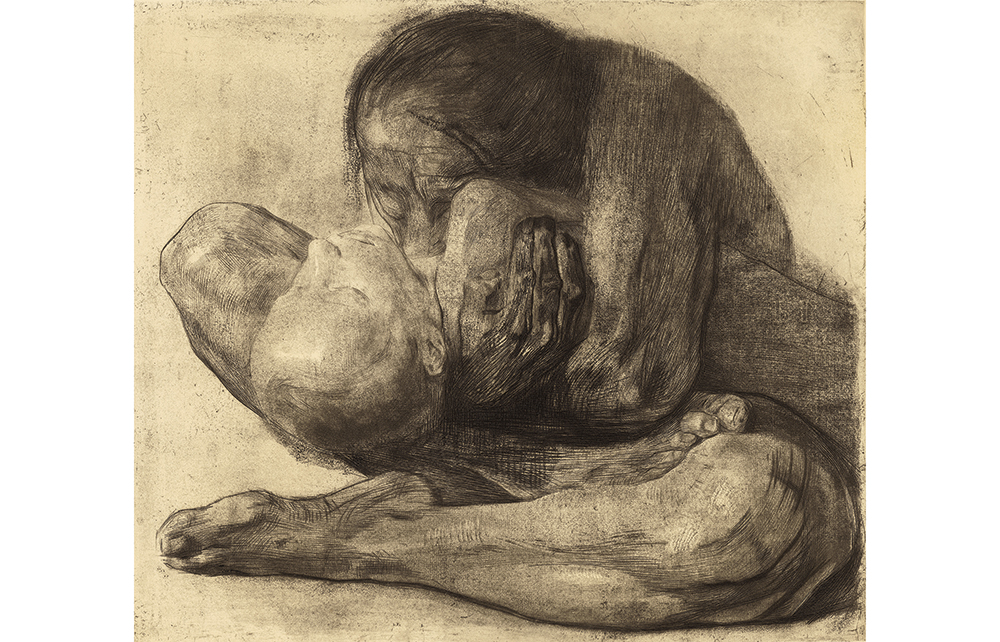

Kollwitz never lets you forget the skeleton under the flesh

The Italian Erma Bossi was drawn into the Russians’ orbit, but the other artists here had little in common. Paula Modersohn-Becker, who married the traditional landscape painter Otto Modersohn after joining the rural artists’ colony of Worpswede, developed her own particular form of modernism during four extended stays in Paris. Jacoba van Heemskerck took lessons from Mondrian in the Dutch artists’ colony of Domburg before converting to Kandinskyesque abstraction. Käthe Kollwitz, socialist wife of a general practitioner serving factory workers in Berlin, had no connection with the other six artists; apart from a couple of woodcuts in the exhibition, her work can hardly be described as modernist.

In a mixed bag of 68 works it’s hard to get a grip on the different artists, especially when, like Werefkin, they keep changing styles.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in