Was Matt Hancock shrugging off Coronavirus in late January? An ‘insight’ article in the Sunday Times which has spread like wildfire online accuses him of doing so. The virus was making its way over the world, it says, but ‘it took just an hour that January 24 lunchtime to brush aside the coronavirus threat. Matt Hancock, the health secretary, bounced out of Whitehall after chairing the meeting and breezily told reporters the risk to the UK public was “low”.’

The ‘Insight’ government deep dive – which curiously appears to have been swerved by the paper’s award-winning political editor Tim Shipman – states that Boris Johnson didn’t chair any meetings about it until March, and that the threat level was kept to ‘moderate’ until mid-February. Several paragraphs imply that Johnson was too busy dealing with his love life – divorce, a secret engagement and a pregnancy – and Brexit to think about a global pandemic that caught nearly every country off guard. You get the overall picture: lazy, complacent Prime Minister and a Health Secretary who took far too long to press the panic button:

One day there will be an inquiry into the lack of preparations during those “lost” five weeks from January 24. There will be questions about when politicians understood the severity of the threat, what the scientists told them and why so little was done to equip the National Health Service for the coming crisis. It will be the politicians who will face the most intense scrutiny.

This is quite true, but we don’t have to wait for that inquiry to fill in the gaps of what happened. In light of the article, government ministers have gone on the offensive over what they perceive to be a hatchet job while opposition MPs are heralding it as proof of Tory incompetence. Whichever side you sit, there are gaps in the Insight report. In the spirit of full disclosure, and with full respect to the paper’s award-winning Insight team, Mr S has emptied his notebook and found plenty of detail that escaped this first draft of history.

1. The breezy health secretary? For all of Hancock’s current difficulties – from testing targets to an ongoing PPE headache – one thing it’s difficult to seriously accuse him of is brushing off the virus in January. If anything, he was boring people about it back then (as those who met him at The Spectator’s Parliamentarian of the Year awards dinner can attest). He held his first Covid meeting in the Department on 6 January and discussed it with the PM the next day. A meeting of Nervtag the ‘New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group’ was held on 13 January.

The stronger criticism of Hancock is that he has been too fixated, too narrowly focussed on the virus and not paying enough attention to the wider health (and economic) impacts of lockdown.

2. How unusual is it for a Prime Minister to miss a Cobra? The article reads: ‘Unusually, Boris Johnson had been absent from COBRA. The committee — which includes ministers, intelligence chiefs and military generals — gathers at moments of great peril such as terrorist attacks, natural disasters and other threats to the nation and is normally chaired by the prime minister.’ While the Prime Minister often leads Cobra meetings, it’s not the norm. Under successive governments, Cobra meetings are designed to be chaired by the relevant Cabinet member the information is relayed back to the Prime Minister. A meeting that focuses on a pandemic would be chaired by the Health Secretary (as it was with Swine Flu in 2009). Hancock chaired Covid Cobra meetings of 24 and 29 January, and the meetings of 5, 12 and 18 February. It’s a stretch to say that the PM somehow skived meetings that he was not supposed to attend.

3. The No. 10 ‘adviser’ The piece says: ‘Last week a senior adviser to Downing Street broke ranks and blamed the weeks of complacency on a failure of leadership in cabinet. The prime minister was singled out.’ This would be a very serious thing for a genuine No. 10 staffer to do. But was this a No. 10 staffer? The phrase ‘a senior adviser to Downing Street’ is not how the Sunday Times usually describes No. 10 sources. It may be because the article has not been penned by the politics team. But the phrasing leaves room for it to be an external adviser to No. 10 rather, than a staffer. In fact, it could be anyone on any committee advising government – and from what the report doesn’t say it seems that the source didn’t have very good access.

4. Hancock blasé on 24 January? ‘But it took just an hour that January 24 lunchtime to brush aside the coronavirus threat. Matt Hancock, the health secretary, bounced out of Whitehall after chairing the meeting and breezily told reporters the risk to the UK public was “low”.’ At the time, ‘low’ was the scientific consensus. But Hancock was, by then, holding daily Covid meetings and had already instructed his department to disregard their ‘central’ scenario and instead operate around for the ‘reasonable worst-case scenario’. Its assumptions were presented to Cobra on… 24 January.

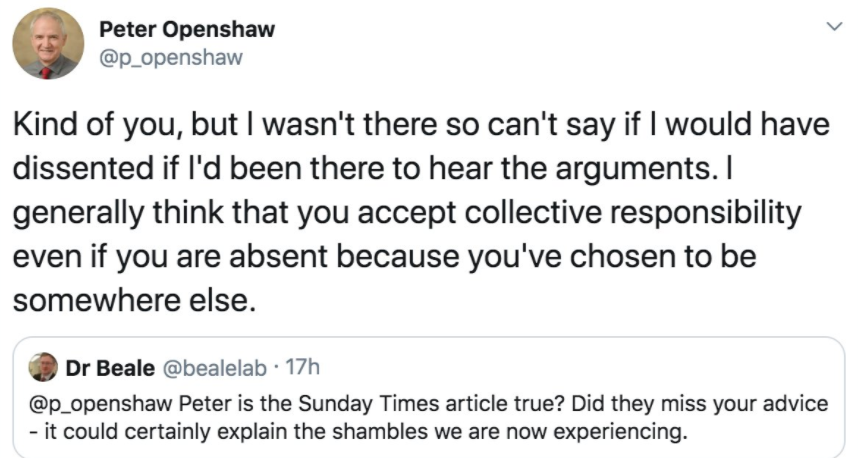

5. Did politicians actually ignore the scientific advice? Various figures are quoted suggesting the UK ought to have acted quicker in updating the risk factor to the country or lockdown measures – but were they actually ignored? One infectious disease modeller – John Edmunds – says that he at one point wanted the government to change its threat level from moderate to high but wasn’t able to actually say this in the meeting because ‘his technology failed him at the crucial moment’. Meanwhile, Peter Openshaw, professor of experimental medicine at Imperial College, says he also would have recommended increasing the threat to high but… wasn’t able to join the meeting as he was in America. Openshaw has since taken to social media to say he accepts collective responsibility on the decision reached in his absence:

Mr S is yet to see the evidence of the government ignoring the advice they were given by their most senior scientific and medical advisers. If there has been a criticism of ministers throughout this process from Tory MPs it’s an over reliance on the scientific advice – with the government repeatedly saying it is the leading component in their decisions.

6. The real problem? When the inevitable inquiry comes out, it’s likely that ministers will be criticised for paying too much attention to the experts, who clung to a palpably-inadequate pandemic response toolkit (for which many thank Jeremy Hunt). When it became clear testing was needed, Public Health England was convinced only it could do so and spurned help that would have been needed to ramp up testing at speed – not to mention the false hope placed on an antibody test. Another issue that will need close examining is PHE’s inability to procure and distribute PPE: the list goes on. This inquiry might also end up asking why no one was more worried about collapse of non-Covid healthcare. But that’s a scandal for another day.

This article is free to read

To unlock more articles, subscribe to get 3 months of unlimited access for just $5

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in