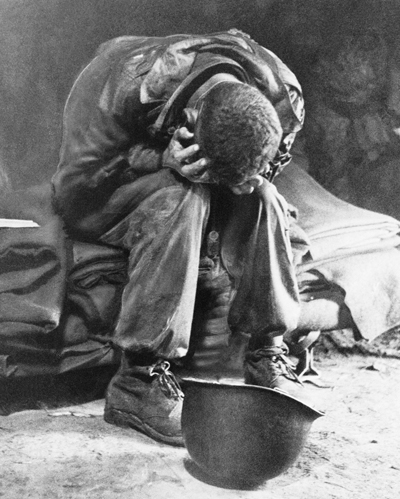

On the morning of 31 January 1945, a private soldier in the United States army, a minor ex-con with a juvenile record for theft, called Eddie Slovik was put to death ‘by musketry’ for desertion at the village of Sainte Marie-aux-Mines in France. There had been no execution of an American soldier for desertion since the Civil War in 1865, but what made Slovik’s death so peculiar was that, in a war that had seen 50,000 American servicemen and 100,000 British desert, his was the only sentence that was carried out. Before his death he said:

They’re not shooting me for deserting; thousands of guys have done that. They just need to make an example out of somebody and I’m it … I used to steal things when I was a kid, and that’s what they’re shooting me for. They’re shooting me for the bread and chewing gum I stole when I was 12 years old.

Slovik was probably right — if you needed to shoot someone pour encourager les autres, an ex-con who had not so much as seen a battlefield must have seemed just about perfect. But the other odd thing about his execution was that it was carried out in secret. In the weeks before his death the military authorities convinced themselves that a stern example was needed to prevent mass desertions in the last bitter fighting of the war; but Eisenhower and the American command knew as well as the British government that the idea of shooting a young boy would have political implications on the home front and for troop morale that their armies simply could not afford.

The death penalty for desertion had been abolished in Britain by a Labour government in 1930; but by 1942 the problem in the Nile delta and the desert had become so grave that Auchinleck was pleading with London for its reimposition.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in