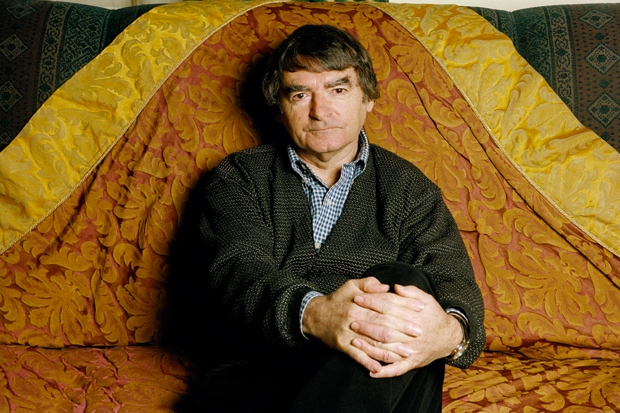

This massive first instalment of a memoir starts in the quite good year the author was born, 1935, and ends with his breakthrough novel, Changing Places, in the rather better year, 1975.

A master-practitioner of narrative, Lodge chooses to write with an artful flatness which recalls Frank Kermode’s similarly self-depreciative memoir, Not Entitled. Lodge’s career was, formatively, in the same provincial, first-generation university orbit. Unlike Kermode (for whom it proved a dubious experience) Lodge never let himself be headhunted into Oxbridge. He turned down the inevitable mid-career offer because, principally, he believed it would be bad for his fiction. And he didn’t think he belonged at high tables.

Lodge first saw the world in working-class East Dulwich. I was born a couple of miles away, in Brixton, a couple of years later. Mine was a not quite so good a year, with the war looming. Both of us were only children of upper working-class parents who wanted more for their offspring. His father was a talented, busking, jobbing musician. My father was a police constable. His mother was a shorthand typist. Mine had been in service, and became a shorthand typist afterwards.

Both Lodge and I were beneficiaries of the 1944 Butler Act which gave clever boys (but only clever boys) what was grandly called a ‘scholarship’. The downside was the kind of deracination Richard Hoggart writes about in The Uses of Literacy. Growing to the light means saying goodbye to your roots. Lodge testifies to the fact that aspiration did not mean surrendering the decencies, strengths and virtues of the class you were born into.

I feel more fellowship with Lodge than some readers of this memoir may. There are, however, major differences. Lodge was a cradle Catholic and is possessed of a major creative talent.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in