This book has taken me far too long to read, and not for the usual reasons (that it’s too long, it’s rubbish, idleness, I lost it, etc.) but because I could only manage ten pages a day before getting a kind of mental nosebleed. And that is because it is so good, so different. There is a note at the back from the publishers, of whom I had not heard: ‘Repeater Books is dedicated to the creation of a new reality.’ There follows some invective about capitalist realism in historical fiction and ends: ‘We are alive and we don’t agree.’ I would say that this book fulfils their brief admirably.

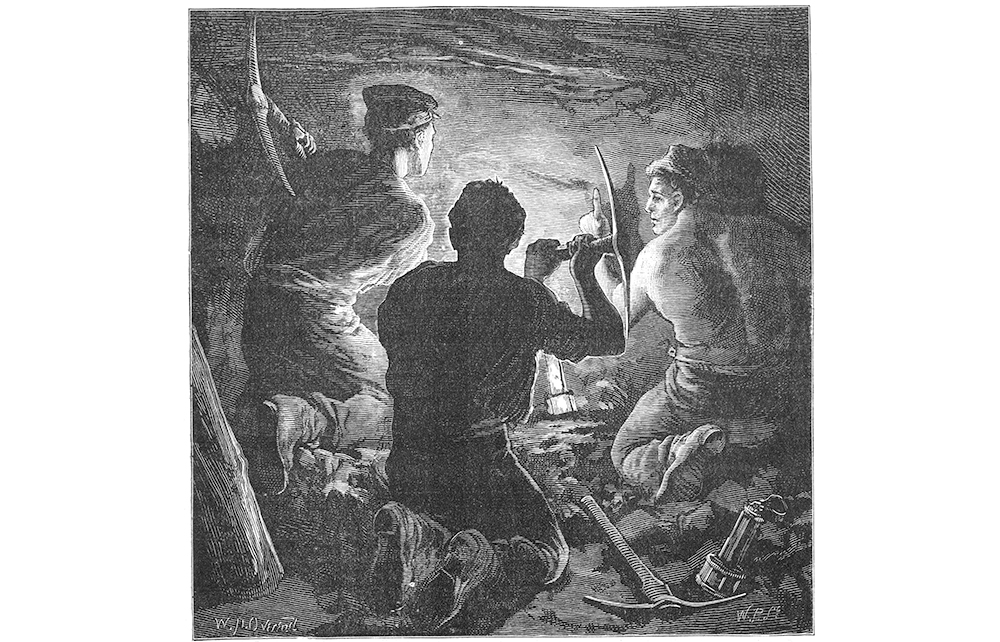

We are in Wales at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. The last wolves are being hunted, the little people have left for the realm of legend and a begrimed and barely literate populace struggles for existence in the shadow of a mountain being hollowed out by new mineworks. And when I say ‘we are in’ I mean we are dumped into a dense thicket of prose without a guide, and through which we can barely see.

The last wolves are being hunted and the little people have left for the realm of legend

This is intentional. Like the peasants in Monty Python, everything and everyone is covered with mud or worse and not even the upper classes can escape. The local dignitary, Sir Herbert, who wants to flood the valley and dam it – and damn the consequences to the people – cakes make-up over the weeping sores on his face, and his wig is infested with vermin. ‘A tiny thing moves in the periwig and shows a jointed leg, then retreats back into the thick white weave.’ I am not joking when I say this is one of the most startling descriptions of just about anything I have ever read in all literature, for it is both delicate and minute, yet also appalling.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in