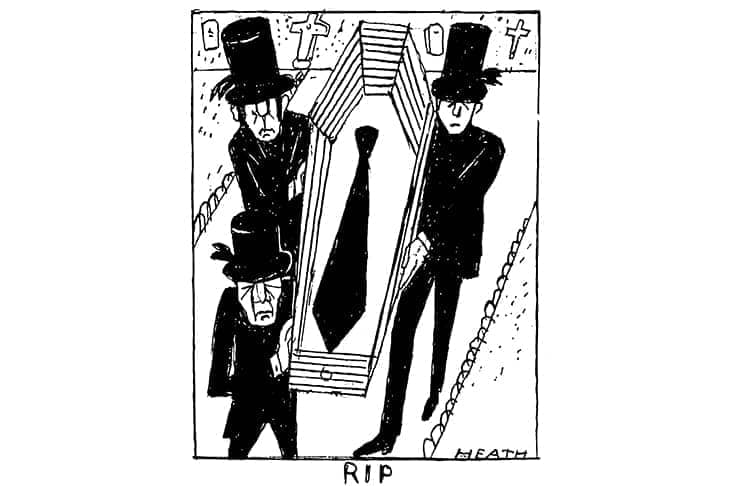

Of all the global trends exacerbated by Covid, the demise of the necktie is probably not the most important. It is, however, worth noting — because the way we dress tells us a lot about who we are.

The tie has been on the retreat as a quintessential item of the male wardrobe for the past 30 or so years. Thanks to all that working from home, it is now at the edge of imminent extinction: soon it will be worn only by eccentrics, dictators or eccentric dictators. The worker bees have returned to their office hives, but on the whole their ties have not come with them.

It cannot be chance that the decline of the tie has coincided with the erasure of everything it once meant to be a man. Masculinity is considered toxic. The tie is being cancelled. You don’t need to be a Freudian to grasp the significance of this.

Not so long ago, almost every British male wore a tie: schoolboys, shopkeepers, bus drivers, policemen, bank clerks, GPs. The history teacher’s was stained with soup. It was unthinkable to leave the house without one. President Clinton would greet guests at the White House by complimenting them on their tie. (For what it’s worth, when Jeffrey Epstein visited he wore a curious dark number with faintly sinister reddish circles.)

The tie has long been a signifier of self-discipline and authority. Yet these are now considered old-fashioned

The tie has long been a signifier of purpose, self-discipline and authority. Even conformity. Yet these are now considered old-fashioned. Indeed, one by one, all have been progressively degraded and consigned to history’s rag bin.

The initial decline of the tie can be dated rather closely to the wave of pop-feminism that followed the Swinging Sixties.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in