When we think of David and Goliath, we think of a young man, not very big, who has a fight with a terrifying opponent, and wins. We think of David as puny and Goliath as towering and strong — not to mention heavily armed. We see David’s victory as something that happened against all odds. The story of David and Goliath is, as Malcolm Gladwell puts it, ‘a metaphor for improbable victory’. Well, that’s how we think about it, anyway. But the thing is, apparently, we’ve got it all wrong.

Gladwell, one of the most influential non-fiction writers in the world, often asks his reader to take a closer look at things. In The Tipping Point, his subject was epidemics. If you study epidemics, he showed us, you can gain insight into lots of other things — like, say, the American Revolution, or the behaviour of consumers. In his next book, Blink, he explained human intuition — how it can work brilliantly, and how it sometimes fails. In Outliers, he showed us that the most successful people are often the people who try hardest. These books are full of human stories, all beautifully told— Gladwell has a wonderfully clear prose style. He wants to tell us how the world works, and how, if you study it carefully, you can increase your chances of coming out on top.

We know David came out on top. That’s because, in single combat, a guy with a deadly projectile weapon is likely to beat a guy who is weighed down with armour. Goliath wasn’t very mobile. He wore a heavy helmet and shin pads made of bronze. David, on the other hand, was a ‘slinger’. Gladwell tells us about slingers in antiquity. They used a contraption made from leather strings and a leather pouch, which they whizzed around their heads, and then let go. Pow! They could fire stones through the air at something approaching 100 mph. Slingers could knock birds out of the sky and ‘hit a coin from as far away as they could see it’.

By the time you’ve read this, you no longer think of David as a petrified kid who got lucky. In your mind’s eye, he’s more like Harrison Ford in Raiders of the Lost Ark, calmly making use of his pistol. And this is the central message of Gladwell’s book. Almost all of us, at some point in our lives, feel like the David of legend — up against terrifying opposition. His point is that we are more like the actual David than we think we are. We’re not some puny kid. We’re Harrison Ford with a pistol. And, just as important: the forces ranged against us are a galumphing throwback hiding behind a shield.

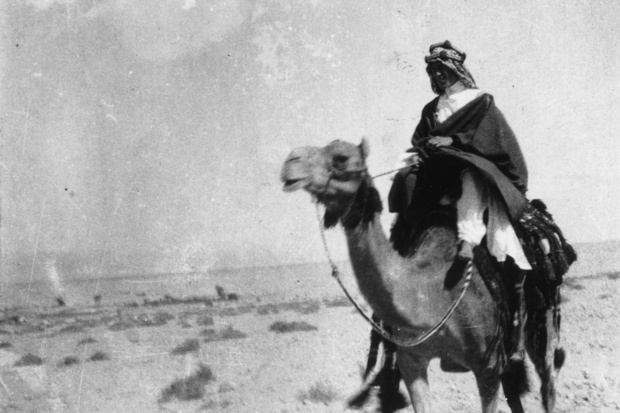

Like The Tipping Point, with its band of revolutionaries, and Outliers, with its people who try and try and try and finally succeed, this is a handbook for underdogs. Gladwell cites the political scientist Ivan Arreguin-Toft, who made a study of wars between strong and weak armies. When one army is ten times as powerful as the opposition, how often does it win? Answer: only 71.5 per cent. But when the weaker side thinks outside the box, it wins almost two-thirds of the time. Think of T.E. Lawrence, who defeated the Turks with his ‘untrained rabble’. The Turks resembled Goliath, laden with heavy weapons and armour. Lawrence’s rabble were like David.

Gladwell has made a collection of Davids, and tells their stories: a girls’ basketball team, who beat stronger opposition by thinking strategically, a top lawyer who overcame dyslexia, a stubborn doctor who made advances in the understanding of lukaemia. This is a cornucopia of underdog-related stuff — how small class sizes in elite schools are not as good as we think they are; how trying to get into the best university is not always the best career move; how those who surmount early difficulties in life often have special advantages. When you have to overcome something, you gain strength. It’s like having a weapon.

One thing remains confusing. If the odds so obviously favoured David, how did the story get so mangled? In any case, Gladwell’s message is clear: travel light, and carry a gun.

Comments